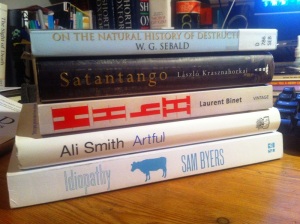

November reading: Krasznahorkai, Binet, Byers

Reading Lászlo Krasznahorkai’s Satantango was a struggle. I wish it hadn’t been, and I’m the first to argue for the improving qualities of difficult books, but this was one that I persevered with in the face of a dwindling conviction that I was going to be able to make any sense of it.

I picked it up largely out of respect for the names on the cover and title page – admiring quotes from WG Sebald (who has loomed large in my reading this year) and Susan Sontag, and the added interest of reading the translation of George Szirtes, lest we forget he is significantly more substantial a literary presence than his marvellous Twitter feed.

I knew nothing about the author, nothing about the book, and took the opportunity to add nothing to this sum before reading – as someone pointed out about the Olympic opening ceremony, the opportunity to sit down to a cultural experience with absolutely no preconceptions is a rare one. Nor have I read anything about the book since finishing it, which I am tempted to do now, in part to see what it is I missed. For a lot of its incredibly dense 270 pages I was trying, trying so hard, to find meaning, discern allegory, pick out the thread or symbol or standpoint that would allow me to take a view on the book as a whole.

I knew nothing about the author, nothing about the book, and took the opportunity to add nothing to this sum before reading – as someone pointed out about the Olympic opening ceremony, the opportunity to sit down to a cultural experience with absolutely no preconceptions is a rare one. Nor have I read anything about the book since finishing it, which I am tempted to do now, in part to see what it is I missed. For a lot of its incredibly dense 270 pages I was trying, trying so hard, to find meaning, discern allegory, pick out the thread or symbol or standpoint that would allow me to take a view on the book as a whole.

Forgive the clumsy phrasing, but never has there been a book so impossible to read between the lines of.

Each of its twelve chapters comes a single unparagraphed block of text (excepting a few interpolated quotations from other, also unparagraphed texts). Which, of course, shouldn’t scare anybody. I wrote earlier in the year about the different densities of Bernhard and Marías on the page, and the lines of Sebald’s Austerlitz are rarely broken. But in those books I found a way in, a way to either enjoy the book sentence by sentence, or understand why the writer, or narrator, was staring me down in this way.

Satantango, a novel set broadly in the Twentieth Century or its analogue, presumably in Hungary or its one, is a muddy, rainy trudge through the lives of a set of villagers (running from the near-peasant to the near-bourgeois) as they seek, or await, deliverance from the unremitting awfulness of their lives – which comes, perhaps, in the form of the charismatic Irimiás and his sidekick Petrina, who might be saviours, might be devils – thoughts of Dostoevsky’s The Devils, Dürrenmatt’s The Visit, and other cheery allegories rise up, but try as I might I couldn’t raise the story out of the mud and rain of its setting. It felt like eating through twelve near-identical loaves of heavy German bread, one after the other.

There were moments of humour, moments of humanity, moments of kitsch – the girl who kills herself with rat poision seemed like a working over of Wedekind’s Spring Awakening so artfully grim it almost made me giggle. But what’s the point? Who ‘are’ Irimiás and his Petrina? What do they represent? I turned the book this way and that, squinting and defocusing my eyes, to see if they would take on some recognisable form – a pair of Beckettian tricksters, Pozzo/Lucky to the hapless villagers, very much more Didi/Gogo in their dealings with authority.

No dice. I don’t know what the book was ‘about’, or what it ‘meant’, which you could take either as a marvellous vindication of the ineffability of literature – that not everything is assimilable to the mind (i.e. reducible to the level) of a 40-year-old bourgeois Londoner who likes reading ‘difficult’ literature because it makes him feel grand – or as a provisional labelling of Satantango as an anti-novel, a book that refuses to ‘mean’, or be ‘about’, anything at all.

What makes us read on, against our better judgement, when it’s so easy to give up – so invigorating to hurl onto the charity shop pile; so tempting to slip a book to the bottom of the pile, telling yourself you may pick it up again another day; and so depressing that there are enough great books already on our shelves, unread and un-re-read to keep us going for years. Sometimes it’s hope, or faith. Sometimes it’s bloodymindedness. Sometime it’s pride.

Sometimes it just seems less effort to keep going than to stop. This is what happened, I think, with a book I read soon after Satantango (in December, actually, but I’m bringing it forward because it fits in well here).

With Laurent Binet’s HHhH it wasn’t so much the names on the cover that made me pick it up, but the feverish buzz and chat about it online and in the literary pages. It seemed to be a book that it was easy to have an opinion on, and thus useful, as a way of negotiating other people’s reading habits and mindsets, if nothing else.

There’s a possibility I would have enjoyed it more if I’d come to it fresh, rather than knowing in advance what kind of postmodern tricks and trappings it was going to pull, but I doubt it. I found it glib and false, in its attempt to transmute its own self-proclaimed callowness in the face of the awesomely authentic and authentically awesome story it set out to tell into a moral stance.

Of course, the story of Operation Anthropoid is a thrilling one, and the innocent dead are tragic, and the historical figure of arch-Nazi Heydrich is a terrible one to have to wrestle into the confines of a literary character, but Binet’s laying bare of his process smacked of over-assurance, every manoeuvre as rehearsed and fake as a television wrestler’s.

It’s something about how you face up to the fact of the linearity of the text, of the wonderful lie of the writer and the reader both working through the words, each from their own side, in the same order. The what-came-before and the what-comes-after of every moment, together with the what-remains-at-the-finish, form an equation that is as unknowable as it is crucial. It’s why I disliked Julian Barnes’ The Sense of an Ending (because it contained a lie of logic and linearity in the attitude of the narrator to his own tale) and why I respect the remainder left heavy in my hands at the end of a Sebald book (because I don’t know what to do with it, but that uncertainty is the very definite product of a particular literary mind).

The truth is, my engagement with the (hi)story of HHhH kept me going, despite the surface distractions, as did my guilt and shame – to which Binet doubtless alludes at one point (I was skimming, by and large) – that I would have been unlikely to even pick up the book had it been an Agent Zigzag-style non-fiction narrative.

I also read more Sebald, for the paper I gave on Creative-Critical Writing at a postgraduate conference, and relaxed on the train with Sam Byers’ Idiopathy, a debut novel from another UEA friend coming out from Fourth Estate in the Spring. (I was reading a proof copy.) It is a strangely breezy read about loneliness and awkwardness of the Contemporary Failed Romantic Relationship that largely eschews plot for the recursive, self-defeating loops of argument and recrimination – of self and other.

It brings to the fore something that feels very real, but which is rarely alluded to in fiction – that most of the arguments we have with our ‘significant halves’ (or anyone we know reasonably well) are – significantly – worked out in advance, on each side. The true expression of the romantic argument is not as caustic or confrontational dialogue, but as repetitive, pointless monologue, and the fact of the causticness, and bitterness, is down to the fact that, usually, the two people are trying to have two different arguments. There is pin-sharp, off-hand satire there (and some that is broader, and less incisively targeted) and a great misanthropic central character in Katherine, whom you may have come across in the extract in Granta’s Britain issue. It’s at times a laugh-out-loud novel, at time a wince-out-loud one.

I add Ali Smith’s Artful to my list as a reminder to myself to go back to it and finish it, now that I’m less tired, and give it my full attention. My first thoughts, sad to say, were that it was just right for my tired mind, and might not benefit from the extra attention. Something, perhaps, to do with it being essays based on talks, which I always find unsatisfying – but then Sebald’s Natural History of Destruction is from a talk, too, and there is nothing tired about that.

As you saw at mine I rather liked Satantango. I wonder if it was looking for the point that spoiled it for you, because there is a sense in which it is an anti-novel; it slips out of grasp and ultimately nothing that happens has any real meaning. There are themes regarding escapism, mortality, but above all for me existence in the absence of meaning which cannot be made meaningful and so cannot in at least one sense be meaningfully represented (as that would be to distort it).

Or something like that.

HHhH somehow never tempted me, which is working out fine so far.