Books of the Year 2022

Reading habits and outcomes change according to personal inclination, of course, but also according to external factors: life circumstances, temperament and age, the demands of a job. All of which is to say I’ve read fewer new books this year than in the past. I review less than I used to, certainly, and when I read for work (teaching Creative Writing at City, University of London) I’m more interested in the books that came out a year or two ago, and that have perhaps started to settle into continued relevance, than the whizz-bang must-read of the year.

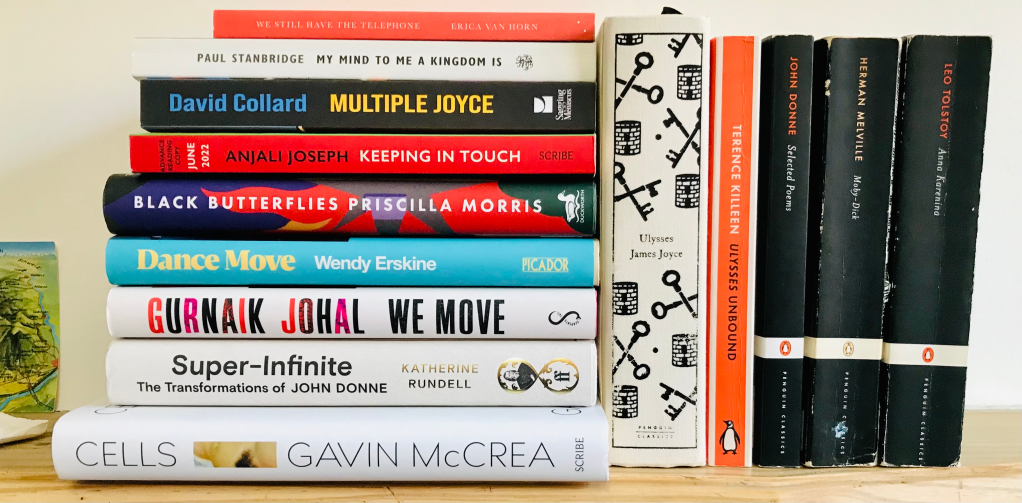

Of the new books I have read, that have made a lasting impression, here are seven:

Ghost Signs by Stu Hennigan (Bluemoose) is an unforgettable journal of the 2020 Covid pandemic lockdown, during which the author was furloughed from his job working for Leeds City Council libraries and volunteered to deliver food parcels to vulnerable people and families. The eerie descriptions of empty motorways and fearful faces peering round front doors evoke that weird time in 2020, but the true and lasting impact of the book comes from Hennigan’s realisation that the poverty and distress he discovers in his adopted city isn’t down to the pandemic at all, but to entrenched government policies that have forced council services to the brink, and thousands of people into shamefully desperate circumstances. It’s a political book, sure, but one written out of necessity, rather than out of desire or ideology, and one that you want every politician in the country to read, and quickly, so that the responsibility for dealing with the issues it raises passes to them, rather than resting with Hennigan. (That’s the problem with writing books like this, isn’t it? That by being the person who identifies or expresses the problem, you become inextricably linked to it, a spokesperson, a talking head, with all the emotional labour that implies.)

(Ghost Signs isn’t in the photo because I’ve given away or lent both copies I’ve owned.)

I heard Hennigan read from and talk about the book at The Social in Little Portland Street, London this year, and the same goes for Wendy Erskine, who was promoting her second collection of short stories, Dance Move (Picador). Erskine is one of the most talented short story writers in Britain and Ireland today, and I’ll read pretty much anything she writes. Dance Move is at least as good as her first collection, Sweet Home, and if you made me choose I’d say it’s better. The stories are muscly, chewy. Erskine has had to wrestle with them, you can tell. They are worked. She takes ordinary characters and by introducing some element that might be plot, but isn’t quite, she forces their ordinary lives into unprecedented but gruesomely believable shapes. These stories are perfect examples of the idea that plot and dramatic incident should be at once surprising and inevitable. But the thing I love most about her stories (I wrote a blog post about it here) is how she ends them:

You are so immersed in these characters’ lives that you want to stay with them, but the deftness of the narrative interventions means that the stories aren’t wedded to plot, so can’t end with a traditional narrative climax or denouement.

(As David Collard said, in response to my original tweets, “Wendy Erskine’s stories don’t end, they simply stop” – which is so true. Perhaps it would be even better to say, they don’t finish, they simply stop.)

So how does she end them? She kind of twists up out of them, steps out of them as you might step out of a dress, leaving it rumpled on the floor. In a way that’s the true ‘dance move’: the ability to leave the dance floor, mid-song, and leave the dance still going.

Take the story ‘Golem’, definitely one of my favourites in the collection. It’s a story that does everything Erskine’s stories do. It densely inhabits its characters’ lives, and it has its comic-surreal interior moments, but most incredibly of all, it manages to end at the perfect unexpected moment. The story goes on, but the narrative of it ends. It departs, exits the room, taking us with it.

Perhaps the best way to put it is that you feel that, yes, the characters are ready to live on, and yes, you’d be ready to keep on reading the prose and the dialogue forever, but no, you wouldn’t want the stories themselves to last a single sentence longer.

My other favourite short story collection of the year is We Move by Gurnaik Johal (Serpent’s Tail), which is a thoroughly impressive debut, that again seems to show how short stories can be the perfect receptacle for characters: they give us characters, rather than plot, rather even than writing, or prose, or words. The difference between this and Dance Move is that We Move, to an extent, looks like the traditional debut-collection-as-novelist’s-calling-card. I’d love to read a novel by Johal – or for Erskine, for that matter, but equally I’d love her to just go on writing stories, because the more people like her keep writing stories, rather than novels, the stronger and more vital the contemporary short story as form will be.

My Mind to Me A Kingdom Is by Paul Stanbridge (Galley Beggar – publisher of my debut novel, though I don’t know Paul) is an exquisite piece of writing that does live or die by its sentences. (Narrator: it lives). An account of the aftermath of the author’s brother, it is indebted to WG Sebald, in terms of the way it leans on and deals out its gleanings of learning, but also in terms of how its lugubriousness slides at times into a form of humour, or perhaps of playfulness. No mean feat when you’re writing about a sibling who killed himself. A hypnotising read.

My most unexpectedly favourite book of the year was Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne, by Katherine Rundell (Faber), which I wrote about for The Lonely Crowd, here. I didn’t know I needed a biography of a Sixteenth Century English Metaphysical poet in my life, but Rundell fairly grabs your lapels and insists you read him. Frankly I’d read any book that contains lines like “A hat big enough to sail a cat in” and “joy so violent it kicks the metal out of your knees, and sorrow large enough to eat you” in it.

My final new book of the year is We Still Have the Telephone by Erica van Horn (Les Fugitives), which I received as a part of a support-the-publisher subscription. It’s a delightfully sly and spare account of the author’s relationship with her mother. “My mother and I have been writing her obituary” etc. One to file alongside Nicholas Royle’s Mother: A Memoir, and Nathalie Léger’s trilogy of Exposition, Suite for Barbara Loden and The White Dress (also from Les Fugitives) as great recent books about mother-child relationships.

A mention here too for Reverse Engineering (Scratch Books) which is a great idea: a selection of recent short stories accompanied by short craft interviews with their authors. It’s got succeed on two levels: the stories themselves have to be worth reading, and the interviews have got to add something more. It succeeds on both, with wonderful stories from some of our best contemporary story writers: Sarah Hall (at her best the best contemporary British short story writer), Irenosen Okojie, Jon McGregor, Chris Power, Jessie Greengrass etc, and useful commentary. I look forward to reading more in the series.

(Copy not shown in photo as loaned out.)

I’ll include another section here on new books, but new books written by writer friends or colleagues: Cells by Gavin McCrea (Scribe) is a jaw-droppingly raw and honest memoir that bristles with insight, and revelation, and liquid prose. Keeping in Touch (also Scribe) is my favourite yet of Anjali Joseph’s novels, a properly grown-up rom-sometimes-com, that makes you want to get on airplanes, travel the world, travel your own country, wherever that is, talk to people, work people out, and fall in love, which is perhaps the same thing. And Black Butterflies by Priscilla Morris (Duckworth) is a novel I’ve been waiting more than a decade to read, and it didn’t disappoint. It’s a moving and delicate told narrative of the siege of Sarajevo, that perhaps wasn’t best served by its publication date just as something horribly similar was happening in and to Ukraine. Finally, 99 Interruptions is the latest slim missive from Charles Boyle, who published my Covid poem Spring Journal in his CB Editions. It sits alongside his pseudonymous By the Same Author as a perfect short book – with the same proviso that it’s so damned slim that it’s easy to lose. And indeed barely a month after buying it I already can’t find it to put in the photo. No matter. I’ll find it, months or years hence, by accident, and enjoy rereading it all the more for that.

For various reasons, this was a strong year for me for successfully finishing fat chunky classics that I’d tried and failed to read in the past: the kind of book I usually can’t read unless I can organise my life around it.

I made a concerted plan to read Ulysses in its centenary year, and did so, starting in January, or perhaps the very end of last December, bouncing between the Penguin Classics Clothbound Edition and a lovely Folio Society edition I’d picked up in a charity shop once. I bolstered myself with guides, including the incredibly useful Ulysses Unbound by Terence Killeen (Penguin), and the joyously digressive Multiple Joyce by David Collard (another writer-friend, published here by Sagging Meniscus). I was also helped by getting Covid in April, mildly enough, thankfully, that I was able to give the necessary time to those tricky last few chapters, but strongly enough that I was able to forgive myself for sometimes skating over the surface of the text, halfway joining Bloom and Stephen in their nighttown hallucinations, and leaving the layers and layers of meaning for later rereads.

A took advantage of the imposed Covid self-isolation to really go for it, and follow Joyce with Anna Karenina, which I’d also tried to read before, but never got more than a couple of short chapters in before moving on to something else. April was mild enough (as my bout of Covid had been mild enough) that I was able to read part of it in a hammock in the garden. A great novel, obviously, but I was less taken with it than, say, Middlemarch (read during the Covid summer of 2020). I loved the expansiveness of it, the descriptions of farming etc, set against those of civil service offices, but I’m afraid I simply didn’t ‘fall for’ Anna and Vronsky in the way I did for Dorothea and Will.

My third doorstop classic of the year was Moby-Dick, which, again, I had definitely tried to read previously, but not managed to stick with. The opportunity presented itself, this time, in the form of a week spent sailing across the Atlantic on a big posh boat. What better place to give myself over to the variegated aspects of whaling, and equally varied thematics of this particular whale, this particular whaler, this particular goddamned world? A high point was a fortuitous meeting in the laundry room of the ship with an American retired English professor who had read M-D many times, and explained how Chapter 36 (‘The Quarter-Deck’) was based on the Christian Mass.

My fourth classic reread was Gide’s The Counterfeiters, which I found less compelling than I probably once had. Annoyingly, at the time I was reading it I couldn’t find Gide’s accompanying text, Logbook of the Coiners, on my shelves, which I’d bought for just this eventuality. Of course, it leapt out at me this morning – while I was scouring the shelves for 99 Interruptions – so maybe I’ll read it now.

I’m bridging the end of the year to the start of next year with a somewhat rushed reread of much of the work of Roberto Bolaño, for a thing, but I’m already keen to know what I’ll follow that with. For, yes, reading habits change, and I do want to keep an equal eye on new and old books… but, at the age of fifty, I do also feel the unread classics weigh upon me, and the classics outside of my local canon. If philosophising is learning how to die, the reading – ‘reading the classics’ – is learning how to have lived.

There is a sense that my thirty years of increasingly intense and engaged reading of new novels, for instance – reading them in the year of their publication or shortly afterwards; keeping up – has been a training for writing, myself, for knowing how the contemporary novel works. And that apprenticeship is, broadly speaking, done. Two novels published. The next, hopefully, to be completed in the new year*. So yes, novels (books, paragraphs, sentences) tell you something about themselves, individually, but taken as tokens of cultural production, they also tell you part of something bigger. They are models, but models that fold out, like a tesseract, to show and make manifest things that they themselves cannot know, are not cognisant of. They offer many and various forms of reading pleasure, that overlay, superadd and sometimes contradict each other, and that is something that the traditional Books of the Year lists cannot acknowledge. A book is something to look at while you are reading a book.

*Hollow laugh as I look back at last year’s Books of the Year post to find this line:

I am close to finishing a first draft of a novel that should have been done a year ago,