Tagged: Lucy Ellmann

Instead of June reading 2021: the fragmentary vs the one-paragraph text – Riviere, Hazzard, Offill, Lockwood, Ellmann, Markson, Énard etc etc

This isn’t really going to function as a ‘What I read this month’ post, in part because I haven’t read many books right through. (Lots of scattered reading as preparation for next academic year. Lots of fragmentary DeLillo for an academic chapter I filed today, yay!)

Instead I’m going to focus on a couple of the books I read this month, and others like them: Weather by Jenny Offill, and Dead Souls, by Sam Riviere. I wrote about the fragmentary nature of Offill’s writing last month, when I reread her Dept. of Speculation after reading Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This (the month before), all three books written or at least presented in isolated paragraphs, with often no great through-flow of narrative or logic to carry you from paragraph to paragraph.

Riviere’s novel, by contrast, is written in a single 300-page paragraph, albeit in carefully constructed and easy-to-parse sentences. And, as it happens, I’ve just picked up another new novel written in a single paragraph – this one in fact in a single sentence: Lorem Ipsum by Oli Hazzard. I haven’t finished it, but it helped focus some thoughts that I’ll try to get down now. These will be rough, and provisional.

Questions (not yet all answered):

- What does it mean to present a text as isolated paragraphs, or as one unbroken paragraph?

- Is it coincidence that these various books turned up at the same time?

- Does it tell us something about ambitions or intentions of writers just now?

- Are fragmentary and single-par forms in fact opposite, and pulling in different directions?

- If they are, does that signify a move away from the centre ground? If not, what joins them?

Let’s pull together the examples that spring to mind, or from my shelves:

Recent fragmentary narratives:

- No One is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood (2021)

- Weather (2020) and Dept. of Speculation (2014) by Jenny Offill

- Assembly by Natasha Brown (2021) – in part, it jumps around, I haven’t read much of it yet.

And further back;

- This is the Place to Be by Lara Pawson (2016) A brilliant memoir written in block paragraphs, but allowing for a certain ‘through-flow’ of idea and argument.

- This is Memorial Device by David Keenan (2017) – normal-length (mostly longish) paragraphs, but separated by line breaks, rather than indented.

- Satin Island by Tom McCarthy (2015) – a series of long-ish numbered paragraphs, separated by line breaks.

- Unmastered by Katherine Angel (2012) – fragmentary aphoristic non-fiction, not strictly speaking narrative.

- Various late novels by David Markson, from Wittgenstein’s Mistress onwards

- Tristano by Nanni Balestrini (1966 and 2014) – a novel of fragmentary identically-sized paragraphs, randomly ordered, two to a page. The paragraphs are separated by line breaks, but my guess is that the randomness drives the presentation on the page.

Recent all-in-one-paragraph narratives:

- Lorem Ipsum by Oli Hazzard (2021)

- Dead Souls by Sam Riviere (2021)

- Ducks, Newburyport by Lucy Ellmann (2019)

And further back:

- Zone (2008) and Compass (2015) by Mathias Énard

- Various novels by László Krasznahorkai, of which I’ve only read Satantango (1985) – a series of single-paragraph chapters.

- Various novels by Thomas Bernhard, of which I’ve only read Correction (1975) and Concrete (1982)

- The first chapter of Beckett’s Molloy (1950) is a single paragraph, as is the last nine tenths of The Unnameable(1952)

- The final section of Ulysses, by James Joyce (1922)

So, my thoughts:

Continue readingMay reading 2021: Offill, Machado, Murata, Slimani, Kristof, Spark

Seven books, mostly quite short. I re-read Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill for what was at least the third time. I think I picked it up as I’d been reminded of it by Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This, which I wrote about last month, and is written in a somewhat similar format. While the fragmentary form in Lockwood’s novel is clearly intended to represent consciousness fractured through Twitter and social media, Offill’s book is less online, and more about consciousness fractured through modern life in general. Offill is more constrained, more zen. The narrator’s brain has filtered the world. Lockwood’s narrator can’t filter the world, and insists on adding to it, interpreting it.

Lockwood’s book, as I said in my post, is unnerving, even enervating to read. Offill’s is restful, even when it turns dark.

Nevertheless, it’s odd that the book seems to lose its way after the halfway mark. It can’t do the melodrama it has promised, through its story of marital breakdown, but it performs a wonderfully neat pirouette to avoid the collision. This happens in the superb chapter 32, in which the narrator confronts her errant, adulterous husband and his ‘other woman’, but undermines her own description with a viciously precise creative writing commentary: “Needed? Can this be shown through gesture?”

The scene that follows reminded me of the equivalent one in Elena Ferrante’s Days of Abandonment. But, where that is brilliantly visceral, this one just crumbles. That said, I suppose the temporary ‘failure’ of the novel is justified by its premise. The narrator is somebody who needs to be in control. That’s what’s behind her compulsive marshalling of facts, which she parcels out in those fragmentary paragraphs. When she loses control, the narrative dissolves into a swamp of entropy and only gradually, and it’s not entirely clear how, works its way back out. She reads a self-help book about surviving adultery, which she sneers at, but which – maybe – helps.

For sure, this book is not a self-help book about fixing a collapsing relationship. For all the nuggets of wisdom it purportedly contains, it’s never clear how they do it, the two of them, the couple and their daughter, beyond moving to the country, the “geographic cure”, which seems a surprisingly old-fashioned resolution to such an untraditionally presented story.

It reminds me of one of my all-time favourite books: Wittgenstein’s Mistress by David Markson. Similar in the fragmentary form, similar in the obsessive relay of facts, and knowledge, and wisdom. (Rilke! The Voyager recording!) All of which is weaponised, and then irradiated. Literature as series of fortune cookies. Knowledge is reducible, and manageable, and transferable, and this is at once a good and a bad thing. (It reminds me, too, of Lucy Ellmann’s Ducks, Newburyport, which I never did/still haven’t finished.)

All three books, or four, counting Lockwood, though perhaps that one less, are about the uselessness of knowledge in the face of the world. Forgert Rilke, forget wisdom. If you want to save your marriage, simply move to the country, get a puppy, chop firewood. Which is lovely, but… really?

In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado is an eye-opening account of an abusive relationship that turns expectations of the sub-genre on their head. The formal invention is impressive and effective, but some things do get lost. The book is a persuasive account of a subjective experience – of being gaslit and abused – and what I missed as a reader was the objective dimension. The ‘woman in the dream house’ – the abuser – remains something of an enigma. What was she like? What was her problem? Of course, this lack, this absence, may well be partly due to the ethical and legal aspect of memoir writing. The ‘woman’ presumably must remain vague in some aspects so she remains unidentifiable, and can’t sue. (I covered some of this in my review of Deborah Levy’s Real Estate.) For all its inventiveness, the book delineates the limits of what memoir can do.

I enjoyed Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata, which I read after listening to Merve Emre and Elif Batuman discussing it on the Public Books podcast. I didn’t agree with everything they said, but I was intrigued in particular about their description of the book as ‘an adultery novel’, i.e. a story build on a simple narrative model of thesis – anthesis – synthesis. I was preparing a workshop on plot and structure in novel-writing (for London Writer’s Café, hopefully more to come in the Autumn!) and thought it would be interesting to see how the novel managed this.

Continue reading(Not) Books of the Year 2019

This has not been a good year for me, reading-wise. Last year’s Year in Reading post features a stack of great books published in 2018 that I was able to enjoy and write about as they came out. For various reasons, this year’s stack is much smaller. This might be simply that there weren’t so many good books, or it might be that I lost my taste for them – for books, for reading.

There are some other mitigating circumstances:

First of all, 2019 was supposed to be the Year of Reading Proust, something I set for myself as a new year’s resolution, with a dedicated Twitter account to accompany it, and give me encouragement. It started well, with the first two volumes done over the first two months, but the third wasn’t finished until I was on my summer holiday. The fourth volume, Sodom and Gomorrah, sits by my bed even now. Proust calls for time properly devoted to it – you have to have time to find time, or speculate to accumulate you might say – and time this year was sucked up by other things.

There were four intense reading projects that got in the way: a blitz through some unread Iris Murdochs ahead of a panel discussion at the Cambridge Literary Festival; rereading some Brigid Brophys as I put together a chapter for an academic book; reading and rereading Don DeLillo for another academic chapter; and currently an avalanche of Simenons for a long piece to be published next year. These were and are all fulfilling and exhilarating in their different ways, but ate up much of my reading/writing energy while they occurred.

Work got in the way: academia is becoming more gruelling. (Academia, in part, means reading lots of things fast to find the things I want my students to read more slowly. It means strategic, points-based, results-oriented reading.)

Writing got in the way, for a time: my morning commute, which is often my best time for reading, suddenly gave itself over to the first draft of a new book – that now, alas, languishes at 45,000 words, untouched in two months. I have no idea when I will get back to it.

A Personal Anthology has been a happy distraction: all those short stories to read! Obviously, I don’t read all of all of them, but the project has sent me in many different and rewarding directions.

There were months this year – September and November – when I didn’t read an entire book front to back, though I never stopped reading. Reading just became scatter-gun, fragmentary, a bit of this, a bit of that, snacking, never finding the book that would suck me in and close off the rest of the world. Perhaps this is to do with teaching (I am always looking for useful examples of types of writing, always classifying, always comparing), perhaps with writing (I am always looking for inspiration, for something in a book that will light the fuse under my own writing; a snatch of writing can be enough).

I’m somewhat in that mood at the moment, on the last day of the year. Knowing that I have a big piece of writing work to do in January (academic bureaucracy) and a big piece in February (the Simenons), I find it hard to settle on any book that I feel deserves my full attention.

Or rather I feel I don’t have enough to offer any book that is going to make demands on me, as a reader. And I have too much pride to reach for something that demands nothing from me.

Instead, I reach for books that I think will steady me, will give an intense shot of what I need without having to read all of it – a ‘livener’ I think you’d call it. Something bracing. So, in the last few days I’ve picked up:

- an Alasdair Gray novel from the four I have unread on my shelves. It was Something Leather. It didn’t do the trick;

- a John Berger book I have read before (Here is Where We Meet), hoping that it would match or else steer my self-pitying end-of-year rudderlessness (it didn’t);

- a big book of RS Thomas poems. That did the trick for one bedtime;

- then Alasdair Gray’s wonderful The Book of Prefaces, which is the very definition of the intellectual livener.

- And then see me walking back up the road from the high street, having dropped off a selection of books at the charity shop, reading the opening to Adam Mars Jones’s book of film writing, Second Sight, a steal at a pound, and instantly, though temporarily, feeling invigorated. Here is someone writing insightfully, fruitfully, encouragingly about culture, making it all seem worth while.

None of those books, though, have been read enough to count as Reading. They haven’t been ‘ticked off’.

So if I look back at my Monthly Reading posts from 2019, I find that the new books I read that I loved the most were not new books at all, but just newly translated. Continue reading

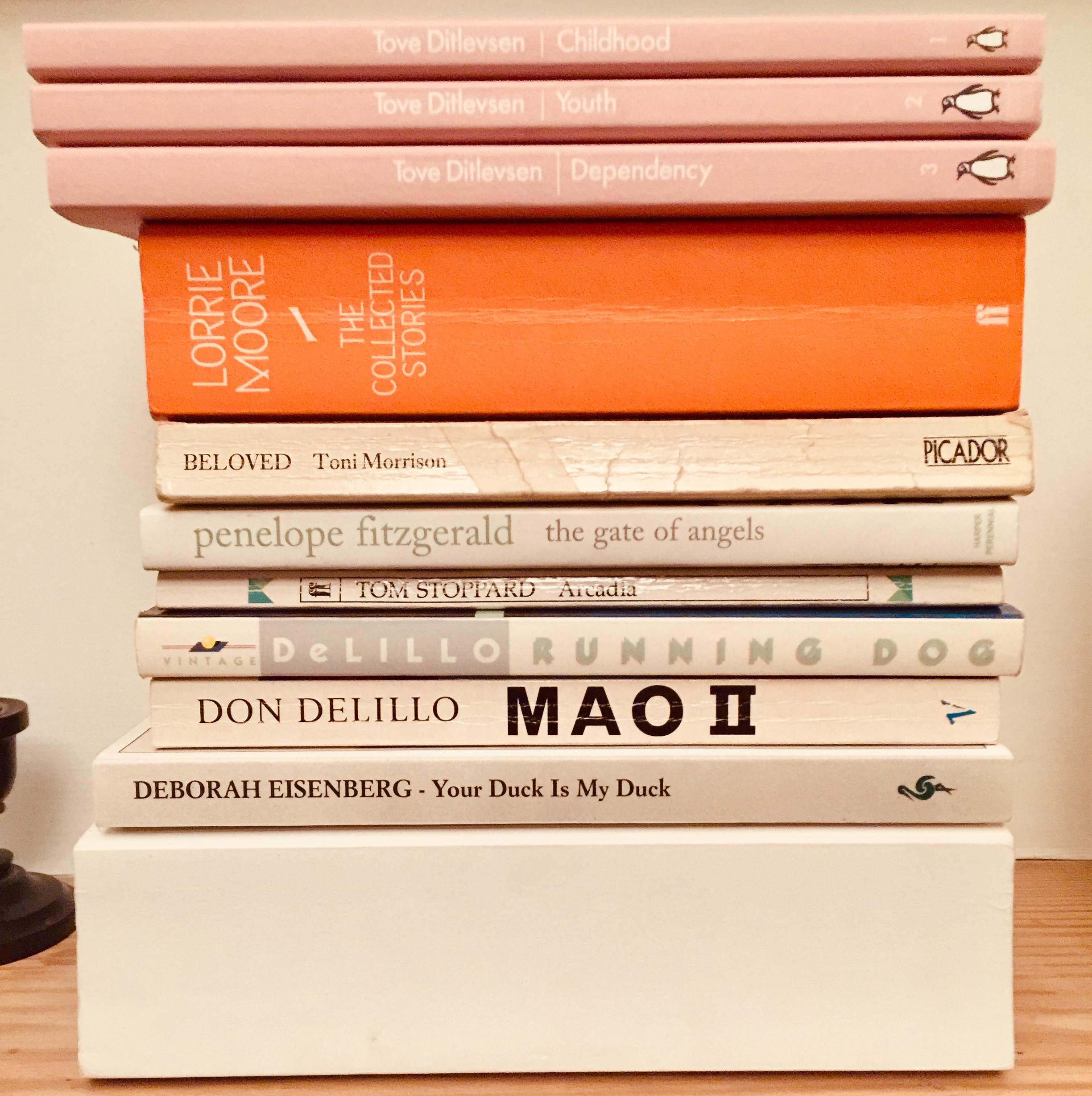

August Reading: DeLillo, Ditlevsen, Eisenberg, Ellmann, Moore, Morrison, Proust

(What a pleasingly alliterative set of author names)

(What a pleasingly alliterative set of author names)

There’s an epigraph that I often remember, from Dave Eggers’ debut A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius (2000 – and boy I wonder if anyone’s read or reread that book recently. It would be an interesting experience.) In fact the book has two memorable epigraphs: firstly, ‘THIS WAS UNCALLED FOR.’; and, secondly:

First of all:

I am tired.

I am true of heart.

And also:

You are tired.

You are true of heart.

Both of them sum up the radical sincerity and potential mawkishness at the heart of his writing. Both, because of this, are memorable. They stay with me, because as statements they are so widely applicable – they are applicable now – as well as being pertinent to the book for which they act as curtain raisers, or perhaps, rather, mottos painted on the safety curtain of the book’s theatre.

I am tired. Teaching starts next week. Summer’s over. I am sure that you are tired. I make no claims for the trueness of either of our hearts, but let’s accentuate the positive.

I am tired. That’s it. That’s the tweet.

And but so:

Books are wonderful relaxation. They are also wonderful energising. There’s nothing I love more than grabbing my phone to tweet a response to something I’m reading, whether it’s Don DeLillo describing a woman putting a condom on a man’s penis as “dainty-fingered and determined to be an expert, like a solemn child dressing a doll”,

No big deal, just a DeLillo sentence describing someone putting a condom on a penis. Fuck sake, Don. pic.twitter.com/i5oBTEN1ly

— Jonathan Gibbs (@Tiny_Camels) August 31, 2019

or Lorrie Moore pole-axing the reader with the devastating end to the first page of her story ‘Terrific Mother’.

Here is the first page of ‘Terrific Mother’. Who else would *dare* to open a story like that? pic.twitter.com/vr4qFHJFXR

— Jonathan Gibbs (@Tiny_Camels) August 22, 2019

I’ve been trying to read Proust with my phone to hand, too, as an enhanced form of annotation, and that, too, has been fun and exciting.

Fun and excitement: wow. That’s it. That’s the tweet.

But, sometimes, writing about books can be a chore. It’s a terrible thing that a book, once read, even a good book, can be put on one side and forgotten. What’s the point of all of this, you think, if a book that engages your brain and emotions over a number of hours over a number of days just gets put back on the shelf and, to all intents and purposes, forgotten? Because sometimes they are picked up again. Sometimes they are passed on. My August reading contained left-turns and blind alleys, slogs up stony hills and brief gleefully shrieking slides down sandy dunes. There was reading for work, reading for the soul, reading by accident and reading by design.

The Don DeLillos are there for an academic chapter I’m writing, and I found myself zooming through them. Mao II, a re-read, is far from my favourite of his novels: too slick and portentous, too glib in the way it throws around its themes.

In one aspect at least it’s a victim of its success. The famous riff about terrorists having replaced the novelists at the heart of the inner life of the culture is blandly prophetic, but it’s too on the nose. The other ‘prophetic’ moments or images in his novels – such as the most photographed barn in America, or the playing dead response to the Airborne Toxic Event, are more oblique, more generally symbolic. The writing is spiffing. It’s spiky poetry has just become too easy to read.

Running Dog, by contrast, I enjoyed. I don’t think I’d read it before. It’s more corny in its plotting – closer to a spy thriller or a contemporary hardboiled thriller – and that allows the author to have more fun, and for the punchier writing to stand out from the more familiar skeleton. Another extract I tweeted managed to pick out something that occurred to me elsewhere about the male (I think) approach to language. Here it is: Continue reading

July Reading: Benedetti, Shepherd, Hyde, Ellmann

I’m coming out of a hectic and not entirely satisfying couple of weeks of reading. I finished the third volume of Proust on holiday, but didn’t have the fourth with me, which lost me impetus. Then the Booker longlist was announced and this sent me back to Ducks, Newburyport, which I had only dipped into but wanted very much to read. Then there was reading for work (variously, and for various reasons, Nick Harkaway, Don DeLillo) and then I read some short stories from the new editions of Granta and Lighthouse, and then one night I couldn’t work out what to read, so turned to Borges, which is my usual response to this problem, and that kept me going for a couple of nights. An unread secondhand copy of a Herman Hesse book, Klingsor’s Last Summer, beckoned when I wanted something to read in the bath, and I found a Hollinghurst in a charity shop I hadn’t read (The Sparsholt Affair) and read the opening pages of that on the train home. There’s a Penelope Fitzgerald re-read face-down and spine-open somewhere in the house. Then, yesterday, Toni Morrison died, so of course I picked up Beloved for the train home. Honestly, it’s a miracle I finish any books at all.

I’m coming out of a hectic and not entirely satisfying couple of weeks of reading. I finished the third volume of Proust on holiday, but didn’t have the fourth with me, which lost me impetus. Then the Booker longlist was announced and this sent me back to Ducks, Newburyport, which I had only dipped into but wanted very much to read. Then there was reading for work (variously, and for various reasons, Nick Harkaway, Don DeLillo) and then I read some short stories from the new editions of Granta and Lighthouse, and then one night I couldn’t work out what to read, so turned to Borges, which is my usual response to this problem, and that kept me going for a couple of nights. An unread secondhand copy of a Herman Hesse book, Klingsor’s Last Summer, beckoned when I wanted something to read in the bath, and I found a Hollinghurst in a charity shop I hadn’t read (The Sparsholt Affair) and read the opening pages of that on the train home. There’s a Penelope Fitzgerald re-read face-down and spine-open somewhere in the house. Then, yesterday, Toni Morrison died, so of course I picked up Beloved for the train home. Honestly, it’s a miracle I finish any books at all.

Here’s what I did read in July, however: three short novels by Mario Benedetti, a Uruguayan writer and poet who died in 2009 and is only now being translated into English. So far Penguin Modern Classics have given us Who Among Us?, The Truce and Springtime in a Broken Mirror. These were all wonderful, three broken-hearted love stories of one kind or another, two of them based around love triangles in which a woman leaves her husband for another man, the other featuring a middle-aged divorcee falling in love with a twenty-something woman working in his office.

So, yes, the vibe is melancholic-masculine, with not all but most of the telling coming from the men’s points of view, giving us the sort of pained, elegiac, romantic narrative that men might sneer at in a similar book written by a woman, and women might roll their eyes at when they read in a book written like this by a man. So there’s a risk that they are overly male-gazey, not a million miles from the kind of thing James Salter wrote at his best, though hopefully in a benign kind of way. (The casual homophobia in The Truce, in which the main character despairs when he learns one of his sons is gay, is harder to squint at.)

I certainly found all three books quite lovely and compelling and drank them down like long cold drinks on a hot day. (I reviewed one of them, Who Among Us?, for The Guardian.) In the review I point out that at least two of the books – Who Among Us? and Springtime in a Broken Mirror – make use of subtly destabilising narrative structures, giving the main characters opportunities to reframe and sometimes retell the events of the story in ways that are effective without being aggravatingly demonstrative. In terms of mood I’d perhaps also say that they have something of the at-a-distance melancholy of Yuko Tsushima’s slim books. I’d definitely recommend them – start with any of them, but why not Who Among Us? It’s the slimmest of the three, and the most seductive in its narrative play.

I absolutely loved Nan Shepherd’s influential nature-writing book The Living Mountain, about her lifelong love for – and built out of her lifelong knowledge of – the Cairngorms. The book was written during the second world war, but not published until 1973. Calling it ‘nature writing’ is somehow reductive, however, despite the beautiful descriptions of animals and especially birds: it seems clear that for her the Cairngorms transcend ‘nature’. Nor, really, is it ‘place writing’. The Cairngorms aren’t a “place”. When she is in them, the mountains become her whole world, so perhaps it should be called ‘world writing’. Continue reading