Tagged: Natsume Soseki

September and October reading: Atkinson, Hesse, Popkey, Sōseki, and a lot of other bits and pieces, honest

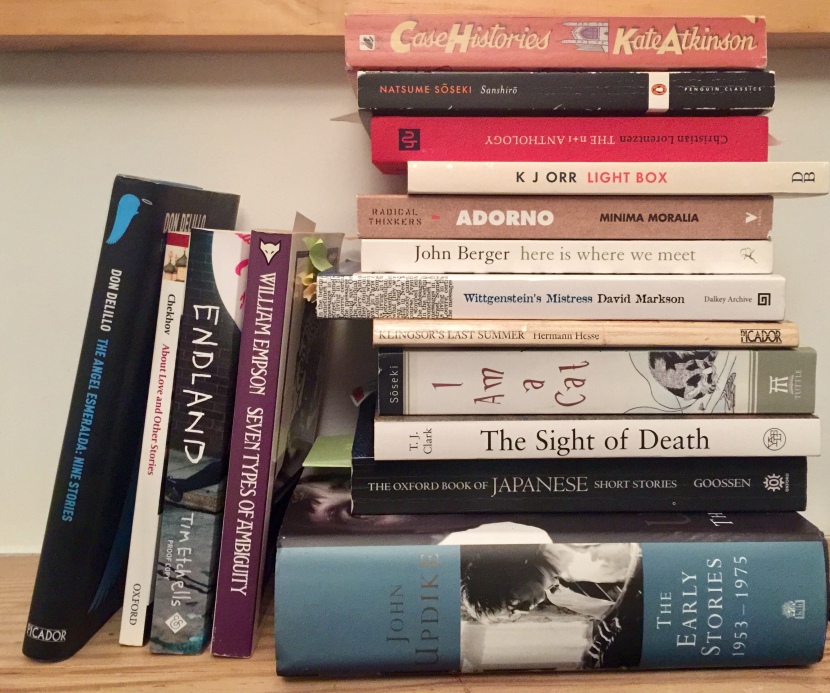

Wow! Look at that pile books! Did you read them all?

No, of course not. Don’t be so stupid.

Reading has been tricky over the last couple of months – I managed to completely miss out on my ‘September reading’, beyond taking a photo of the relevant book pile. The truth is, I didn’t read all of ANY of the books stacked up under September with the exception of Klingsor’s Last Summer, by Hermann Hesse, which is really just three stories slung together. (Bonkers in part. Boringly chauvinistic in the main.) The only other books I’ve read in toto since the beginning of September, when I raced through Running Dog by Don DeLillo are:

- Case Histories, by Kate Atkinson

- Topics of Conversation, by Miranda Popkey

- Sanshirō, by Natsume Sōseki

But, as I’ve written before, much of my reading is piecemeal. I mean, look at all those other books I picked up, read a bit of, and put back.

Why is this? Perhaps it is to do with the attention deficit that is supposedly affecting us all. Perhaps it is to do with my job, in which I have to read lots of students’ work. Perhaps it is to do with my online project A Personal Anthology, in which every week I ask someone to pick and introduce a dozen favourite short stories… I mean, it’s not like I read all twelve, every week, but I always read at least a few of them, both those I don’t know and those I do. (For instance, oh man, ‘Gusev’ by Anton Chekhov, as picked by Darragh McCausland!) Perhaps it’s the fact that I happen to be judging the Manchester Fiction Prize this year, alongside Nicholas Royle, Lara Williams and Sakinah Hofler, which means much of my spare time is spent reading entries. And perhaps it’s to do with the fact that this year I set myself the project of reading all of Proust, for the first time. (I’m not going to make it, by the way. But hey-ho, it was always just a project.)

But there is more to it than that.

I write. I review (less, just now). I teach. Much of my life is taken up with books and literature and writing, and for that I’m profoundly grateful. But the constant irruption into my eyes of real, good, meant words from all sides – a river of words bursting into an overwhelmed house through every opening – means that whole books have to fight to stake their claim.

To put it another way, the idea of a novel – which is, to be blunt, my foundational idea of what words, put together, can achieve – has started to seem crucial, less joyous.

The novel is the type of book above all which insists on being taken as a whole. It is a monad, as Leibniz would have had it; an absolute unit, if you know your memes. It ring-fences its words, encases them in a protective membrane, so as to stop you from taking any of them except on its own terms. A story or poetry collection is built to be divisible. A non-fiction book, even a piece of narrative nonfiction, can be thought of as containing information in discrete units, separable and parsable without the whole.

The novel is the thing that says: I only make sense if you read all of me. It’s all of me, or nothing! No cherry-picking allowed.

A novel is best read, in my experience, either slowly and steadily, over a week or two, in sedate and regular portions, so that your imagination comes to a reasonable accommodation both with the narrative pacing and with the demands of everyday life, negotiating between the two of them, making space for one in the other, and for the other in the one – or it is best read at a gallop, picked up at every opportunity, a page snatched here or there, between bites of breakfast, between meetings, between conversations: this novel consuming your every waking thought.

Over the last couple of months, I’ve been able to do the latter – twice, with Topics of Conversation and Case Histories – but not the former, or not successfully. Sanshirō is the kind of book that would work perfectly as a leisurely fortnight’s read: not much happens; the chapters are short; the characters are agreeable. (It might help to know that the book was originally serialised in weekly instalments.) You could read a decent chunk of it on a good-length train journey.

(It is the third novel by Sōseki that I’ve read, and certainly it doesn’t reach the poetical highs of Kusamakura or the tragic depths of Kokoro. It is a calmative, a thoroughly delightful and spring-like story about a young man come from the country to Tokyo to study at the university, but although I enjoyed it, it didn’t fit the slightly frantic rhythm of this particular autumn.)

What does a novel have to do, then, to grab you by the collar and force you to read it? To elbow its way into your life and take up temporary residence? Well, an itchily cryptic plot is one way to do it. Case Histories is the first book I’ve read by Kate Atkinson, though I own maybe four or five of them. I keep picking them up, trying the first page or two, then putting them back. (Probably best skip the next paragraph if you’ve not read it, and get to Matilda Popkey, as there will be plot-spoilers.)

Case Histories is Atkinson’s first novel featuring a now-recurring private eye, Jackson Brodie, and from reading it you’d think that she didn’t particularly intend to ever bring him back: the end of the book seems to gift him with the kind of narrative closure most series-writers would only dream of when they’re 95% sure they want to retire their egg-laying goose. (When they’re 100% sure, of course, they close them down completely.) The book is also at odds with the crime genre itself in terms of narrative structure. It opens with the matter-of-fact description of three unconnected family tragedies taking place over x years – one disappearance, and two murders. It’s a bravura performance, with none of the shivery glee with which the worst kind of crime thrillers serve up dead or gone girls and husband-topping psycho-bitches. But much of the rest of the book’s plotting is devious in the extreme, basically challenging the reader to work out not just the mystery of who did the crimes, but the secondary mystery of how these disparate narratives are going to come together, other than that Brodie is investigating them all. They do, in simple and more tangential ways, but it’s a bit of a slight of hand. You couldn’t write more than one mystery book this way.

That reaction only comes right at the end, however. On the way there you are treated to a wonderful mixture of the plottish and the character-led. The book is character-driven, you might say, but by characters who can’t drive very well. It reminded me of Iris Murdoch, for its plainly, even humdrumly unusual characters – but an Iris Murdoch who either can’t write well, or doesn’t care for good writing. I mean, Atkinson is a whizz at plotting, at characterisation, and there is some splendid dialogue here – I laughed, I turned the pages, zip-zip-zip – but at no point in the book did a sentence slow me down, or make me catch my breath, or suggest I reread it or underline it or tweet. Reading the book was like eating a huge bowl of plain pasta, cooked exactly as you like it, but with no sauce. It seemed almost willed. She’s clearly too good a writer not to know what she’s doing. Now I need to read some of her other books to see if she makes anything else of it.

Miranda Popkey’s Topics of Conversation I won’t go into here in detail, because I hope to be able to review it. It’s an excellent debut that splashes around in the currently warm waters of autofiction. You might say it’s a touch derivative – and in fact it has an incredible two-page acknowledgements section at the back that lists all the books, films, essays, plays and pasta recipes that inspired it, however tangentially. It’s wonderfully in your face. To be glib, it’s Rachel Cusk by way of Sally Rooney. But it deserves something more than glibness. I want to read it again, slower. I’m tired. Some more books just arrived. I’m off to not read them all, from cover to cover.

Many thanks to Serpent’s Tail for the Popkey, which is out in February 2020.

What is a ‘chapter’ anyway? Reading Natsume Sōseki’s Kokoro – now with answers

I was inspired by a tweet from Niven Govinden (who’s reading his The Gate) to put down The Magic Mountain (it will wait for me) and pick up Natsume Sōseki’s Kokoro, as recommended to me by David Hayden, when I mentioned how much I loved Kusamakura, probably the best known of this Meiji-era Japanese novelist’s books.

I am enjoying Kokoro, which is the story of the friendship between a young and an old man, but one thing is confusing, or annoying, me. The novel (234pp in its elegant Penguin Classics edition, not counting introduction etc) is divided up into 110 chapters, the vast majority of which – do the maths – are two pages long.

Despite their brevity, the chapters are often not self-contained, but some four or five of them may cover the same scene, and run directly on from one to the next. As an extreme example, here is the end of Chapter 26 and the beginning of Chapter 27, during which the narrator and ‘Sensei’, as he calls his friend, are sitting in a garden, talking. Continue reading

What is ‘reading’?: A failed blog post about books

About a year ago I began writing a monthly post on this blog responding to the books that I had read over the last month – not reviews so much, nothing so considered; more a summation of what had stuck with me from those books. It’s not that I don’t like book reviews – people pay me to do those – but that I wanted to move beyond the balanced, culturally-engaged appraisal they call for to see if there was more to get out of writing about books once the books had been finished, put down, half-forgotten, and allowed to relax into the seething primordial swamp of read books, their sentences lost among the millions of other sentences read, processed, filed, erased. (It’s no surprise that I count among my favourite critical books Nicholson Baker’s U&I and Geoff Dyer’s Out of Sheer Rage.)

I kept it up for all of 2012, not always posting on time – but then not all of the books were timely books – and letting myself slip only for December. And, indeed, what I found as the year went by is that single issues, single books, tended to dominate the posts. Some months had photographs of big piles of books at the top (nine, ten, eleven books), some three, or even two. Sometimes those books were big books, and so took up lots of reading time (January 2013 I’ve been reading Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, which doesn’t leave much head space for anything else) but sometimes I had read other books but didn’t much feel like writing about them.

Then there’s the question of how you actually define reading. For a book to be read, must it be completed? Properly engaged with? Where do you draw the limits? If I’ve ‘been reading’ The Magic Mountain does that mean I’ve not ‘been reading’ anything else? No. Also by my bed is Bettany Hughes’ The Hemlock Cup: Socrates, Athens and the Search for the Good Life, which I’ve been dipping into after a discussion of philosophy books with my good friend Neil and his son Harrison, who’s just starting to study the subject at school. As part of that discussion I took down from the shelf my favourite philosophical anthology Porcupines – that got read, too, a bit.

Last Saturday, while supposedly watching Borgen on television with my wife, I found myself dipping into another of my favourite ‘dipping into’ books, Clive James’s book of essays Cultural Amnesia; I read two or three entries, including his spirited takedown of Walter Benjamin Continue reading