Tagged: Thomas Bernhard

Instead of June reading 2021: the fragmentary vs the one-paragraph text – Riviere, Hazzard, Offill, Lockwood, Ellmann, Markson, Énard etc etc

This isn’t really going to function as a ‘What I read this month’ post, in part because I haven’t read many books right through. (Lots of scattered reading as preparation for next academic year. Lots of fragmentary DeLillo for an academic chapter I filed today, yay!)

Instead I’m going to focus on a couple of the books I read this month, and others like them: Weather by Jenny Offill, and Dead Souls, by Sam Riviere. I wrote about the fragmentary nature of Offill’s writing last month, when I reread her Dept. of Speculation after reading Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This (the month before), all three books written or at least presented in isolated paragraphs, with often no great through-flow of narrative or logic to carry you from paragraph to paragraph.

Riviere’s novel, by contrast, is written in a single 300-page paragraph, albeit in carefully constructed and easy-to-parse sentences. And, as it happens, I’ve just picked up another new novel written in a single paragraph – this one in fact in a single sentence: Lorem Ipsum by Oli Hazzard. I haven’t finished it, but it helped focus some thoughts that I’ll try to get down now. These will be rough, and provisional.

Questions (not yet all answered):

- What does it mean to present a text as isolated paragraphs, or as one unbroken paragraph?

- Is it coincidence that these various books turned up at the same time?

- Does it tell us something about ambitions or intentions of writers just now?

- Are fragmentary and single-par forms in fact opposite, and pulling in different directions?

- If they are, does that signify a move away from the centre ground? If not, what joins them?

Let’s pull together the examples that spring to mind, or from my shelves:

Recent fragmentary narratives:

- No One is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood (2021)

- Weather (2020) and Dept. of Speculation (2014) by Jenny Offill

- Assembly by Natasha Brown (2021) – in part, it jumps around, I haven’t read much of it yet.

And further back;

- This is the Place to Be by Lara Pawson (2016) A brilliant memoir written in block paragraphs, but allowing for a certain ‘through-flow’ of idea and argument.

- This is Memorial Device by David Keenan (2017) – normal-length (mostly longish) paragraphs, but separated by line breaks, rather than indented.

- Satin Island by Tom McCarthy (2015) – a series of long-ish numbered paragraphs, separated by line breaks.

- Unmastered by Katherine Angel (2012) – fragmentary aphoristic non-fiction, not strictly speaking narrative.

- Various late novels by David Markson, from Wittgenstein’s Mistress onwards

- Tristano by Nanni Balestrini (1966 and 2014) – a novel of fragmentary identically-sized paragraphs, randomly ordered, two to a page. The paragraphs are separated by line breaks, but my guess is that the randomness drives the presentation on the page.

Recent all-in-one-paragraph narratives:

- Lorem Ipsum by Oli Hazzard (2021)

- Dead Souls by Sam Riviere (2021)

- Ducks, Newburyport by Lucy Ellmann (2019)

And further back:

- Zone (2008) and Compass (2015) by Mathias Énard

- Various novels by László Krasznahorkai, of which I’ve only read Satantango (1985) – a series of single-paragraph chapters.

- Various novels by Thomas Bernhard, of which I’ve only read Correction (1975) and Concrete (1982)

- The first chapter of Beckett’s Molloy (1950) is a single paragraph, as is the last nine tenths of The Unnameable(1952)

- The final section of Ulysses, by James Joyce (1922)

So, my thoughts:

Continue reading

April reading: White Review Short Story Prize, Ben Lerner… but mostly: why I read so few women writers, and how you can help me kick the habit

Okay, so here’s my pile of books from April. Some can be dispensed with quickly: the Knausgaard I wrote about here; the Tim Parks was mentioned in my March reading, about pockets of time and site-specific reading; the Jonathan Buckley (Nostalgia) was for a review, forthcoming from The Independent; the White Review, though I read it, stands in for the shortlist of the White Review Short Story Prize, which had my story ‘The Story I’m Thinking Of’ on it.

In fact, a fair amount of April was spent fretting about that, and I came up with an ingenious way of not fretting: I read all the other stories once, quickly, so as to pick up their good points, but I read mine a dozen times or more, obsessively, until all meaning and possible good qualities had leached from it entirely, and I was convinced I wouldn’t win. Correctly, as it turned out, though I’m happy to say I didn’t guess the winner, Claire-Louise Bennett’s ‘The Lady of the House‘, the best qualities of which absolutely don’t give themselves up to skim reading online. It’s very good, on rereading, and will I think be even better when it’s read, in print, in the next issue of the journal.

That leaves Jay Griffiths and Edith Pearlman. Giffiths’ Kith, which I have only read some of, I found – as with many of the reviews that I’ve seen – disappointing. Where her previous book, Wild, seemed to vibrate with passion, this seems merely indignant, and the writing too quickly evaporates into abstractions. In Wild, Griffiths’ passion about her subject grew directly out of her first-hand experience of it – the places she had been, the things she had seen, lived and done – and the glorious baggage (the incisive and scintillating philosophical and literary reference and analysis) seemed to settle in effortlessly amongst it. Here, the first-hand experience – her memories her childhood – are too distant, too bound up in myth.

The Pearlman – her new and selected stories, Binocular Vision, I will reserve judgement on. It’s sitting by my bed, and I’m reading a story every now and then. The three that I’ve read (‘Fidelity’, ‘If Love Were All’ and ‘The Story’) have convinced me that she is a very strange writer indeed, and perhaps not best served by a collected stories like this one.

Those three stories are all very different, almost sui generis, and each carries within itself a decisive element of idiosyncrasy that it’s hard not to think of as a being close to a gimmick. They all do something very different to what they seemed to set out to do. They seem to start out like John Updike, and end up like Lydia Davis. Which makes reading them a disconcerting experience, especially when they live all together in a book like this. It makes the book seem unwieldy and inappropriate. I’d rather have them individually bound, so I can take them on one-on-one. Then they’d come with the sense that each one needs individual consideration. More on Pearlman, I hope.

The book that I was intending to write more on, this month, was the Ben Lerner, Leaving the Atocha Station, which I read quickly (overquickly) in an over-caffeinated, sleep-deprived fug in the days after not winning the White Review prize, which also involved a pretty big night’s drinking.

But my thoughts about Lerner are very much bound up in a problem which is ably represented by the book standing upright at the side of my pile: Elaine Showalter’s history of American women writers, A Jury of Her Peers. This was a birthday present from my darling sister, who, if I didn’t know her better, might have meant it as an ironic rebuke that I don’t read enough women writers. Continue reading

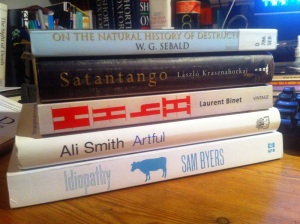

November reading: Krasznahorkai, Binet, Byers

Reading Lászlo Krasznahorkai’s Satantango was a struggle. I wish it hadn’t been, and I’m the first to argue for the improving qualities of difficult books, but this was one that I persevered with in the face of a dwindling conviction that I was going to be able to make any sense of it.

I picked it up largely out of respect for the names on the cover and title page – admiring quotes from WG Sebald (who has loomed large in my reading this year) and Susan Sontag, and the added interest of reading the translation of George Szirtes, lest we forget he is significantly more substantial a literary presence than his marvellous Twitter feed.

I knew nothing about the author, nothing about the book, and took the opportunity to add nothing to this sum before reading – as someone pointed out about the Olympic opening ceremony, the opportunity to sit down to a cultural experience with absolutely no preconceptions is a rare one. Nor have I read anything about the book since finishing it, which I am tempted to do now, in part to see what it is I missed. For a lot of its incredibly dense 270 pages I was trying, trying so hard, to find meaning, discern allegory, pick out the thread or symbol or standpoint that would allow me to take a view on the book as a whole.

I knew nothing about the author, nothing about the book, and took the opportunity to add nothing to this sum before reading – as someone pointed out about the Olympic opening ceremony, the opportunity to sit down to a cultural experience with absolutely no preconceptions is a rare one. Nor have I read anything about the book since finishing it, which I am tempted to do now, in part to see what it is I missed. For a lot of its incredibly dense 270 pages I was trying, trying so hard, to find meaning, discern allegory, pick out the thread or symbol or standpoint that would allow me to take a view on the book as a whole.

Forgive the clumsy phrasing, but never has there been a book so impossible to read between the lines of. Continue reading

August reading: Marías, Bolaño, Villalobos, Rivière

Ah, August reading! From the date of this post it is clear that the days of August reading are gone. School and work and house and chores have breached the walls and flooded back in to cover that prized, fertile land, with its flowers of leisure that bloom but once a year.

August means holidays, which means, most often, camping somewhere warm, and thus the chance to do that thing I never really liked to do on holidays before I had kids: lie by a swimming pool, slathered in suncream, while obnoxious children (not all of them my own) and undressed, unlookatable (for a variety of reasons) adults screech and splash and loll, and give myself over to the hour-by-hour mental massage of immersion in a good, long book. How else do you think I read 2666? Or The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle?

This year I decided to take with me the final volume of Javier Marías’s mammoth novel Your Face Tomorrow, which comes in seven parts: Fever, Spear, Dance, Dream, Poison, Shadow and Farewell, two parts each in the first two volumes, the last three in the third. I remember when I read the first volume, it was on a different kind of holiday, in a cottage on the damp, misty north Norfolk coast, not so sure about the second, but after a couple of failed housebound attempts at the 544pp third volume I knew I needed time and space to read it, which I definitely wanted to do.

This year I decided to take with me the final volume of Javier Marías’s mammoth novel Your Face Tomorrow, which comes in seven parts: Fever, Spear, Dance, Dream, Poison, Shadow and Farewell, two parts each in the first two volumes, the last three in the third. I remember when I read the first volume, it was on a different kind of holiday, in a cottage on the damp, misty north Norfolk coast, not so sure about the second, but after a couple of failed housebound attempts at the 544pp third volume I knew I needed time and space to read it, which I definitely wanted to do.

Time and space is needed not just because of the length (you don’t need to go on holiday to read Ulysses, it suits itself quite naturally to the jittery stop-start motion of modern city life) but because of Marías’s writing style, which isn’t that far removed from that of Thomas Bernhard in the length of its sentences and paragraphs. Pages look like dry plateaux, with the cracks of a former riverbed only appearing occasionally, Continue reading