Tagged: Michel Houellebecq

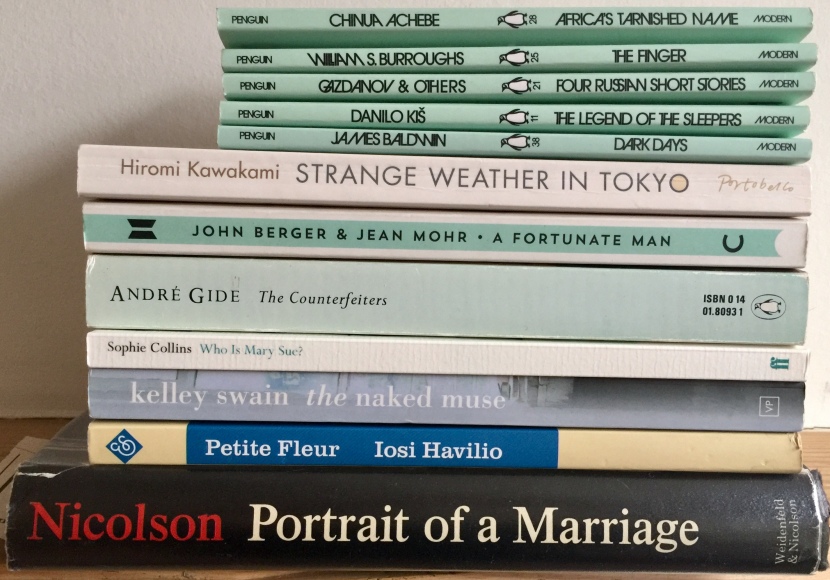

February reading: Gide, Havilio, Berger, Kawakami, Swain, Collins, Nicolson and Sackville-West

I turned to The Counterfeiters this month after rereading and thoroughly enjoying Gide’s Strait is the Gate, which I’d read when a teenager, along with his lyrical and prophetic The Fruits of the Earth. I’d also read his more straightforwardly existentialist The Vatican Cellars, but for some reason had never got around to this, his other longer novel. I preferred Strait is the Gate, I have to say, for its gem-like precision. Nothing is wasted; everything is focused on the tragedy of the novella’s central relationship. The Counterfeiters (translated again by Dorothy Bussy) is one of those novels that must have been terribly shocking when it came out, for its depiction of nihilistic young French men talking about setting up avant garde literary journals, and probably being homosexual. Shocking – or thrilling, if you get a thrill from the idea of other people being shocked by what you read.

None of that really carries over today. It reads like the sort of literary ‘group novel’ that crops up every now and then. I remember one, by an author I know can’t remember, called All the Sad Young Literary Men, which is a great title absolutely not in need of a novel to justify it. Nor, really, is there any shock to the aesthetic frisson of Gide breaking the fourth wall to talk directly to the reader about his characters, and his confusion about where the novel is going. Admittedly the frisson is greater than, or different to, that in, for example, Tristram Shandy, because The Counterfeiters is not “Shandy-esque”: it is by and large a realist novel, and not interested in playing postmodern games, so the gentle looks-to-camera do give something of a jolt. It took me a couple of weeks to read the book, largely at bedtime, and I admit that I rather lost track of who all the disaffected young men and their decadent older friends were, and got them all confused with each other, meaning that the moral impact of the narrative was lost on me. But the Wildean dialogue was enough to keep me amused.

The last book I read in the month was Petite Fleur, by Iosi Havilio, translated by Lorna Scott Fox (And Other Stories, proof copy, for which much thanks!). This is a book short enough to read in one day, on the commute to and from work – though admittedly snowy delays did rather help with the logistics of that. This Argentinian novel carries comparisons on its cover to Tolstoy and César Aira, and the second of those is spot-on in terms of its gleeful, light-as-air ludicrousness – that bottoms out into terrible clarity just when you hope it won’t. I shan’t say much about the plot, as its pleasures come through its masterful sequences of bluffs, feints and double-bluffs, and these deserve not to be spoiled. I’ll say, though, that while it took me a fair few attempts to learn how to enjoy Aira’s output (by taking each book as a part of a broad, diffuse project, rather than a fully independent entity) Havilio manages to build that bold sense of randomness into this one book. The Tolstoy comparison is more uncertain. You’ll see why it’s mentioned when you read the book, but really we’re closer to Gogol than Tolstoy, in the book’s full-pelt playfulness with what readers think novels should be. I realised ten pages in that I’d tried to read it once before, and given up on it. I can see now that I must have been distracted. Elements that I had found merely confusing, before, now carried the full charge of the absurd. It’s a shame, too, about the title, which again makes sense when you read the book, but is hardly representative, and is frankly a bit shit. If Fever Dream hadn’t already been taken, you could call it Fever Dream. I preferred this to Schweblin’s book. Continue reading

Unspeakable behaviour, of the very best kind: Ten fictional artists

“Tell me this,” says a character in Don DeLillo’s novel, Falling Man: “What kind of painter is allowed to behave more unspeakably, figurative or abstract?”

It would be easy enough to rack up examples on both sides, from fiction, no less than from real life. Novelists love artists as characters, after all. If books furnish a room, then artists furnish a novel – with their artworks, and their antics. You might say they are the perfect writer’s avatar: analogue, clown and straw man rolled into one. Their created work is so much more describable than prose, their creative act too. And they get to have models, some of them, to go to bed with.

My novel, Randall, is, in intention, an satirical and elegiac alternative history of Young British Artists and art world in general, and while writing it I’ve naturally collected a menagerie of other fictional artists, sometimes badly behaved, sometimes not, but all exemplary in the way they dramatize an aspect of human nature that is, by definition, out there.

The Horse’s Mouth, by Joyce Carey Continue reading

A short screed against boredom

I don’t know where @LeeRourke was yesterday when he tweeted ‘Photographs of writers’ rooms are boring.’ but I know where I was when I read it. I was on the train, absolutely the best place for Twitter – and the worst. (I wonder how many of those quickly-regretted footballer tweets we’re continually reading about are made on the coach home after the match, adrenaline still pumping, forced to sit still?)

I joined in the enjoyable flurry of tweets which followed, and which included, from @badaude, ‘boring is best’ and, again from Rourke, ‘I heart boring :-)’. Which were perhaps meant, if not exactly ironically, then at least lightheartedly. But they still got my goat.

Boring is not good. Boredom is the enemy, and I get antsy when I see it raised up as some kind of goal in life.

It is a very modern theme. Rourke’s debut novel, The Canal, was blurbed as “a shocking tale about… boredom”, David Foster Wallace’s unfinished novel, The Pale King, too, takes boredom as one of its subjects, Continue reading