Tagged: Brian Dillon

‘After my own heart’: an occasional post after Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence

I was reading Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence last night, in the way that you’re supposed to, dipping into it, looking for something to snag my interest – either the writer of the sentence in question, or the sentence itself, or something Dillon might have to say – and I alighted on his section on Elizabeth Bowen, whose stories I also happen to haphazardly reading at the moment, because I’m reading Tessa Hadley’s stories, Hadley being a fan and literary descendent of sorts of Bowen… and, anyway, I read this passage:

As I write, I’m two thirds of the way through A Time in Rome, which [Bowen] published in 1960, and I think I have found, again, a writer after my own heart. How many times does it happen, dare it happen, in a life of reading? A dozen, maybe? There is a difference between the writers you can read and admire all your life, and the others, the voices for whom you feel some more intimate affinity. Could Elizabeth Bowen be turning swiftly into one of the latter, on account of her amazing sentences?

Which is marvellous, and sparked two particular thoughts, last night, and has sparked a couple more, this morning, as I sit down to write, on a Bank Holiday Sunday morning, at just gone 8am. There’s one, on the phrase “after my own heart”, that I really want to get to, so I’ll try to dispatch the other ones briefly.

Firstly, the word ‘affinity’, which is obviously an important word for Dillon: it was the name of Dillon’s next book, after all. It could just as easily have been the title of this one. What interests me about the word, however, is its aura of neutrality. When we think of the connections that get built between – as here – us as individual readers, and particular writers, we tend to look to one or the other as the active agent in the relationship. Either the writer is a genius – they seduce me, impress or overawe me – or I love the writer, I find something particular in them. But an affinity is bipartisan, and objective, as if unwilled by either. The chemical usage of the word is the most critically productive one, especially after Goethe applied it to human relationships in Elective Affinities, but in fact the original meaning was to do with relationships – in particular relationships not linked by blood, such as marriage, or god-parentship. I suppose, contra Goethe, what I like about the term is that these affinities that Dillon is talking about seem to be un- or non-elective, but weirdly, inexorably fated.

(NB I haven’t read Affinities yet, so maybe Dillon goes into all this in his book.)

The other brief thought from this morning was that, although Dillon does talk about Bowen’s fiction in his piece on her, the sentence he picks to write about is from her sort-of-travel book A Time in Rome. And this made me think of the death, last week, of Martin Amis, and how much of the online critical chat had an undercurrent of favouring the non-fiction (the journalism, and the first memoir) over the fiction (with a few exceptions, usually involving Money), and I wondered if anyone had really considered, at length, the legacy of writers that had written both fiction and non-fiction, and what it meant when one was favoured over the other. Susan Sontag wanted to be remembered as a novelist, but isn’t, and won’t be. It would surely appal Amis if he felt that it was his book reviews and interviews that we remembered him for. Geoff Dyer does talk about this a bit with reference to Lawrence in Out of Sheer Rage, but I’d like to read something broader. If a writer has a style, and that style is to an extent consistent over their fiction and non-fiction, then what are the conditions by which they become remembered, and stay read, after their death, for one rather than the other? Or, alternatively, is there a difference in terms of how a similar style applies to fiction, and non-fiction?

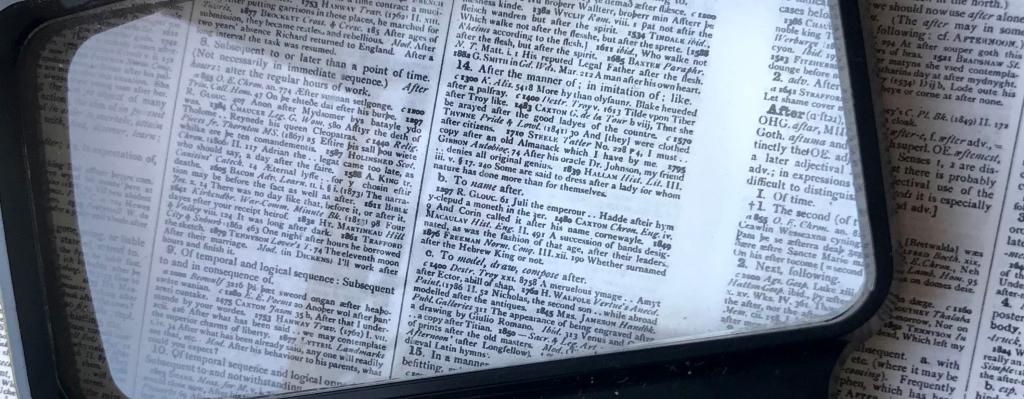

Now to the original point I wanted to make. Dillon’s paragraph on his relationship to Bowen is lovely, and I’m sure many readers will relate to it, as I did, but I was particularly struck by the phrase a writer after my own heart. “After my own heart” – it’s a strange and wonderful idiom, and sent me – it’s a Bank Holiday weekend – to the dictionary. ‘After’, after all, is a preposition that, like most prepositions, has a variety of different uses.

“After my own heart” could, for instance, have a sinister intent, as with hounds after a fox. The writer in pursuit of the reader’s heart. But it doesn’t mean that. It means “after the nature of; according to”, a usage going back to the Bible (“There is therefore now no condemnation to them which are in Christ Jesus, who walk not after the flesh, but after the Spirit”, Romans 8:1-2) – though the specific usage of “a man after his own heart” isn’t recorded until 1882, when it appears in, of all places, The Guardian, attributed to one G. Smith.

But the other meanings or uses of ‘after’ hover around the word. ‘After’, too, in the sense of “after the manner of; in imitation of”, as it’s used in art history – for example, Picasso’s The Maids of Honor (Las Meninas, after Velázquez). I remember a novel called After Breathless, by Jennifer Potter, that I read simply because it was inspired by A Bout de Souffle, my favourite film. “After my own heart” as critical interrogation.

And then the word ‘own’ in the phrase, too: after my own heart. It’s a phrase that is deeply, reverberantly embedded in the language from which it grows. It’s a phrase to conjure with. It’s an idiom, in other words.

My final brief thought, and again someone has probably written on this, but what exactly is the relationship between idiom and cliché? Does an idiom have to pass through the state of being a cliché before it can achieve this linguistic apotheosis? Is an idiom merely a cliché that has freed itself of the negative connotations of overuse – overuse with a single meaning – to allow itself to take on other meanings. Because that’s the problem with clichés, isn’t it? Not that they’re overfamiliar as phrases – as signifiers – but because their overuse has obliterated the meaning the phrase intends. The site of meaning has been rubbed raw.

Books of the Year 2020

The best books of the year – or rather the books that gave me the best reading experiences. Meaning the deepest, highest, widest, closest, most pleasurable. In all the strange ways we measure pleasure.

Well, I’d better start by saying I finished my complete, first reading of Proust – which I’d started on 1st January 2019 – on 31st May 2020. The plan had been to read the whole thing in a year, but by October 2019 I was still only on volume 4, and the last date that year (I took to writing the date in the margin to mark where I finished reading each day) was 21st October, halfway through that volume. I picked it back up in February 2020, beginning again at the start of vol 4, and made good progress through lockdown. All along I jotted thoughts and posted screenshots on a dedicated Twitter account (@proustdiary), and if I had the time I would try to scrabble together and collate these into something more coherent. It was a major reading experience, yes, full of great highs but also full of longeurs and swampy sections to trudge through. Don’t go reading it thinking it’s like other novels. It’s not.

Other major reading experiences of the year from books not published in the year:

- Middlemarch, read for the first time, on holiday in that odd distant summer window when I was lucky enough (for lucky read privileged) to be able to spend 10 days on a Greek island. Not just a wonderful, exemplary novel, it is also a vindication of the very idea of the Victorian novel, of what it can do: stolid realism, intrusive omniscient narration, all the things we like to think we do without in our literary style today.

- The Third Policeman. I’d tried At Swim, Two Birds before, more than once, and never got far with it, admiring its precocious undergraduate wit without being convinced that it would develop into anything more worthwhile. This one, though, tugged at me from the first pages, and delivered, in all dimensions. The spear, and the series of chests! The lift to the underworld. The ending! My god, the ending. Let me kneel before the scaffold, which must be the best piece of tactical diversionary business in the history of literature. Read it, then let me buy you a beer to talk about it. (By the bye, I’ve been reading Kevin Barry’s Night Boat to Tangier, on and off, this last month or so – for so slight a book, it’s taken a long time to get through – and you think: oh man, you have talent, but you don’t have that bastard’s wicked spear, so sharp it will cut you and won’t even notice. “About an inch from the end it is so sharp that sometimes – late at night or on a soft bad day especially – you cannot think of it or try to make it the subject of a little idea because you will hurt your box with the excruciaton of it.” Recommended to me by Helen McClory, to whom I am grateful.

- Midwinter Break by Bernard MacLaverty. My first by him. The kind of writing I feel able to aspire to. Precise building of characters in the round. All tilting towards a moment. That moment in the Anne Frank House. It made me reconsider VS Prichett’s line about a short story being something glimpsed out of the corner of your eye. That particular scene could have made a great short story, and it would have remained a glimpse. Sometimes, however, a novel can be a heavy and ornate or structurally robust frame or scaffold designed to hold a glimpse, and the glimpse hits home harder than it ever would at the length of a story.

- Autumn Journal. My true book of the year. From March to August I read it every day, as I was writing my own poem, Spring Journal, given out first on Twitter, and now published by CB Editions. I learned so much about metre, and rhyme, from immersing myself in it.

But, of books published this year:

The Lying Life of Adults by Elena Ferrante (translated by Ann Goldstein, Europa Editions, not pictured as lent out) was my novel of the year. Such a relief, to start with, that she was able to follow the Neapolitan Quartet, and with something that was neither a shorter version of those books, nor a return, quite, to the short vicious claustrophobia of the three brilliant standalone novels. It is perhaps less fully distinctive than any of those works – more similar, in scope, to what other people write as novels, but no less pleasurable for that. I read it, along with Middlemarch, on holiday, and it gave me the great pleasure of holiday reading, of allowing reading time to overflow the usually watertight boundaries of hours and activities, of blocking out the world. It’s strange, isn’t it, how we go to lovely places on holiday – places with great views, great landscape, and great climate – and read. I mean, you could lock yourself up in your bedroom and read, for a week, but you don’t. (If you can afford to, you don’t.) There must be something about the climate and landscape that improves the reading, or something about the reading that makes the landscape and climate more precious, for being ignored, or not being made the most of. The Ferrante reminded me of Javier Marías – who, incidentally, I had auditioned for taking on that same holiday, buying Berta Isla in anticipation, but I glanced at it a few times before setting off and, chillingly, found it utterly unappealing and most likely dreadful.

Similar in a way to Ferrante’s quartet was Ana María Matute’s The Island (translated by Laura Lonsdale), another essential discovery from Penguin Modern Classics. I reviewed it on this blog, here. As I say there, it was the incantatory aspect of the narration, calling back over the years to the lost friends, lost love, lost self, that stayed with me from reading it.

2020 saw the publication in translation of Natalie Léger’s The White Dress (translated by Natasha Lehrer, Les Fugitives), the third part of her trilogy of monograph-cum-memoirs that began – in English – with Suite for Barbara Loden, and continued with Exposition (those two were written and published in French in the opposite order). What a set of books these are! As strong on the furious waste of female artistic talent, and the general and specific ways that men, and male social and cultural structures, set out to achieve this end, as anything by Chris Kraus; as simply, naturally adventurous in its manner of navigating its different forms as Kraus or Maggie Nelson. Each book is brilliant, no one of them is put in the shadow by the other two, but the ending of The White Dress – this book is about Pippa Bacca, an Italian performance artist who was abducted, raped and murdered while hitchhiking across Europe to promote world peace – is as sickeningly powerful in its effect as the end of Spoorloos (The Vanishing). You feel helpless. I wrote more about The White Dress in a monthly reading round-up, before these petered out, here.

I chose Nicholas Royle’s Mother: A Memoir (Myriad Editions) and Amy McCauley’s Propositions (Monitor Books) as my books of the year for The Lonely Crowd. They’re both brilliant, and you can read my thoughts on them here.

Another memoir that I devoured, and that gave me tough minutes and hours of thinking and reflection, even as, on the page, it sparked and effervesced, was Rebecca Solnit’s Recollections of my Non-Existence (Granta). In a way it’s the opposite to Royle’s book, which is only ever caught up in the flow of time as if by happenstance. Royle’s mother happened to live through certain years, and be of a certain nationality and generation, so the exterior world does impinge, but impinges contingently. (The book is about personality, and how personalities bend towards, away from and around each other in a family.) Solnit’s book, by contrast, is absolutely caught in the flow of time. Solnit is who she is because of when she lived, and lives. In this it’s somewhat similar to Annie Ernaux’s superb The Years, which I wrote about here, and chose for my Books of the Year in 2018. And it’s as intelligent and insightful as Léger’s books, though Solnit has no reservations about writing about herself. (Léger, you feel, can only write about herself by way of writing about others. She is reticent, and so to an extent subject to the ego. Solnit writes memoir without ego.) This is certainly the book of Solnit’s that I’ve enjoyed the most.

From memoir to essays – and yes there is a lot of non-fiction on this list, among the new books I mean. I’m not sure why this is. There are other contemporary novels and short stories (in collections, journals, on their own) that I’ve read this year that I enjoyed, but none of them impacted on me as heavily as these books. Perhaps it’s because fiction is less concerned with its impact on the reader here and now, it drifts into the timeless time of world and story that must, perforce, be largely unlinked to the phenomenal world. By contrast, all these essays address me, here today, and demand something of me. (Incidentally, timeliness is not a guarantee of meaning. I tried reading Zadie Smith’s ‘lockdown’ essay collection Intimations, and found it rather insipid. It seemed like noodles and doodles, when Solnit, Léger and Ernaux, as good as sat me down and talked important things to me, things that needed to be said.)

I very much enjoyed Elisa Gabbert’s The Unreality of Memory and Other Essays (Atlantic), the essays of which seemed to spring from the world – they are about disaster, ecological crisis, terrorism, things that we know as it were unknowingly. They are unknown knows. The subjects seemed to be held still by Gabbert as if by force of will, in a way that seems different from the other non-fiction pieces mentioned here. They were not a natural outpouring or distillation of insight – as, for example, and famously, was Solnit’s brilliant ‘Men Explain Things to Me’ – but worked pieces, pieces Gabbert had to work at, to get right, topics she had to apply herself to in order understand them, to bring them under the law of her thought. She was forcing herself to think, and we were beneficiaries.

Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence (Fitzcarraldo) is a characteristically intelligent, urbane, distinguished set of essays that focus on particular writers by zooming in on – and then building out from – single sentences of their writing. They are master-classes, and they remind me of Clive James’s Cultural Amnesia, though that book ranged more widely (James ranged more widely, full stop). Suppose a Sentence is wonderful because what it offers is unapplicable. You can’t use it for anything else. Its lessons are oblique. It’s like a walking tour of a part of the city you’d never found on your own, and never will be able to again.

Exercises in Control by Annabel Banks (Influx Press) was perhaps the most interesting new collection of short stories I read this year. The stories are mostly short, and don’t try too hard to be polished or well-rounded, nor to be artfully extraordinary. But they grab you with their insouciance, their not-caring. The story ‘Rite of Passage’, with a girl (I should say ‘woman’) who crawls into hole in a rock on a beach on a date, was thrilling for its unpredictability. It didn’t quite have the courage of its convictions, in the end, but many of the stories left me feeling deliciously unmoored.

Finally, my other book of the year, it goes without saying, was The Snow Ball by Brigid Brophy, reissued by Faber, my favourite novel of one of my all-time favourite writers, who is hopefully becoming better known. This book was, to some extent, the model for my last novel, The Large Door, set, like Midwinter Break, in Amsterdam. I love The Snow Ball with a reader’s passion, that is say excessive, partial, formed by circumstance and transference.

- The following books were courtesy of the publishers: The Island, The Snow Ball, The Lying Life of Adults, The White Dress, Suppose a Sentence. Thank you to Penguin, Faber, Europa Editions, Les Fugitives and Fitzcarraldo.

Books of the Year 2017

The Back of Beyond by Peter Stamm (Granta)

This is my third (or fourth?) Stamm novel, and before I picked it up I was worried I was beginning to settle into something of a pattern with his books. While I’m reading them, I’m transported; the prose – as before, in Michael Hofman’s translation – is impeccable; the situation presented is both eminently plausible and horrifying suggestive. This is realist fiction with the skin peeled off, showing modern human beings (genus: white, usually middle-class Europeans) at their most ordinary, but vertiginous. There, you think, there but for the grace of God – or possibly the grace of Peter Stamm. But, when I think back to some of the previous Stamms I’ve read, I find they have evaporated in my memory, or else reduced themselves to vivid, isolated moments. This one, I can guarantee, will not do that.

The ordinary couple at the heart of the story are a middle-class heterosexual couple, the parents of two young children, just returned from a holiday and preparing for the return to school and work. Only, while Astrid is upstairs, settling their son, her husband Thomas just… walks out. He puts down his wine glass and leaves through the garden gate. Brilliantly, Stamm treats the reader to both sides of this drama, giving us the disappearance and its aftermath in alternating sections told from Thomas and Astrid’s perspective. Novel of the year?

Being Here is Everything: The Life of Paula M Becker, by Marie Darrieussecq, translated by Penny Hueston (semiotext(e)/Text Publishing)

I reviewed this for minorlits, and stand by my assessment, that it is as good as 2015’s Suite for Barbara Loden. They’re similar books in that they’re biographical essays that take a fresh approach to the now familiar job of bringing into the light the lives and work of unjustly forgotten female artists. For both books, that approach involves a personal and fragmentary style that seems to avoid the usual biographical narrative, as if there is something inherently monolithic and stultifying to it, as if it is secretly in service to the patriarchy.

Whereas Natalie Léger’s portrayal of Loden’s treatment by her husband and director Elia Kazan is unambiguously critical, Darrieussecq is more uncertain about the role of the poet Rilke in Becker’s life. They had a close connection. He wrote a long commemorative poem about her on the anniversary of her death, but did not name her in it. He could have done so much more, she deserved so much more. Non-fiction book of the year.

An Overcoat by Jack Robinson (CB Editions)

Charles Boyle’s CB Editions is one of my favourite indie presses. It’s a true one-man operation, based on Boyle’s excellent taste, no-bullshit attitude and willingness to stand in line at the Post Office with an armful of Jiffy bags on a regular basis. So I was sad at this year’s news that the press is going into semi-retirement – but I was cheered by the arrival, this year, of not one but two small books by Boyle himself, writing under his pen name Jack Robinson. Robinson is a righteously angry book about Britain, Brexit, boys’ schools and the legacy of colonialism, but it’s An Overcoat that has stuck with me, for its delightful hop, skip and a jump along that unstable line that separates fact from fiction.

In it, Henri Beyle (known to most of us as Stendhal, author of The Red and The Black) finds himself in an afterlife in small-town England. He hangs out in cafes, tries to date a woman called M, treats the life of contemporary Britain to the dispassionate observation we wish we had time and the eyes for. Unbeknownst to him, however, the book’s author is annotating the narrative with reference to Beyle’s life and work. It is about as far removed from an academic book on Stendhal as you could imagine, but it is very true to his spirit – true to Boyle’s lifelong love of his writing – as well as being true to the spirits of, for example, WG Sebald, Rachel Cusk, Patrick Keiller. Boyle is one of Britain’s best publishers. He is also one of its most intriguing experimental novelists. If he sold as many books as he deserves to, he’d be a National Treasure, and we cannot allow that to happen. Neither-one-thing-nor-the-other of the year.

Blue Self-Portrait by Noémi Lefebvre (Les Fugitives)

In my review of Blue Self-Portrait for the TLS I described it as Bridget Jones as told by Thomas Bernhard, which was glib. But what Lefebvre does, that is at least partly Bernhardian, is treat the neuroses of her female narrator as worthy of close attention. The book is a plotless wonder, a short ride in the fast machine of a narrator’s overheating, near-to-stalling consciousness – in this instance, a woman flying back from a city break in Berlin to her home town of Paris, accompanied by her sister. Mostly what she’s thinking about is the German male composer she met there and had drinks with, but didn’t accompany back to his apartment – though the romantic aspect of their not-quite-relationship is the least of it. This is neither a love story, nor its opposite. It is about personhood, about how we dare to try to be someone different from other people, and the risks that this entails.

Under My Thumb, edited by Rhian E Jones and Eli Davies (Repeater Books)

I picked this up on spec in Waterstones at Waterloo (good that they’re giving table space to indies like Repeater, which is run by the former staff of Zero Books) in part because I’m writing a novel at the moment set in the music industry – that treats, in part, the issue of sex, as in the issue of groupies, as in the issues of misogyny and sexual predation. I’m trying to address the difficult question of whether it is possible to even imagine rock and pop music without sexual oppression, and the slightly more straightforward question of what we should do about rock and pop stars who abused their power to sexually manipulate women, and girls, in the past.

What’s useful, for me, about this collection of essays is how the authors put their own love of music (rock, pop, hip-hop, soul) on trial. How can you deal with the fact that you love the Stones, Spector, Tupac? How and when is it possible to separate the art from its creator? Standout articles include Fiona Sturges on her love for AC/DC, which she was able to pass on to her daughter until it came to the idea of seeing them live, and Frances Morgan on Michael Gira from US alternative band Swans, who has been accused of abusive behaviour by an ex. Morgan is a fan, and has interviewed the musician in the past. Her essay is a thoughtful exploration of her feelings around the situation and the ethical implications. There have many similar pieces since the Weinstein vocalisation, but this was written before that explosion. The book is full of women thinking carefully about their responses to the actions of culturally significant men. As such, you might call it a mirror for magistrates.

My House of Sky: The Life and Work of JA Baker, by Hetty Saunders (LIttle Toller)

I was looking forward to this book ever since the estimable Little Toller books launched their crowdfunder for it. JA Baker was the author of The Peregrine, one of the seminal works of contemporary nature writing, published in 1962. It’s a strange book that is short on what you’d call proper ornithology, and very much faces in the opposite direction to the whole ‘nature as therapy’ subgenre that has led to books like H is for Hawk. It follows Baker’s obsessive hunt for the falcon across the reclaimed coastal landscape of the Essex coast over a series of winters. (It’s a landscape I know well from my childhood, as the son of an Essex birdwatcher; I found it dull then, but – no surprise – am haunted by it now.) Baker made a point of identifying himself with the peregrine in his book, but it’s the land, not the bird, that he seems to disappear into.

The Peregrine was a big success, but Baker wrote one only other book, which flopped. Other than that, he stuck to his marriage, his Chelmsford council house and his birdwatching, but suffered from encroaching ill health until his death in 1987, at the age of 61. Saunders has done a good job in fleshing out the mystery as best she can, and the book is beautifully produced, with reproductions of Baker’s maps and notebooks that recall Rachel Lichtenstein and Iain Sinclair’s book about David Rodinksy. But in truth Baker was no Rodinsky, and what there was in him that was interesting, you’d have to think, he successfully poured into his one great book. So, while this is a book that was called for, and one to cherish, it is perhaps a slight disappointment for those of us who had invested so much in the areas of Baker’s map that had previously been so tantalisingly blank. Some blank areas on the map, I suppose, are blank because there’s simply nothing there.

Essayism, by Brian Dillon (Fitzcarraldo)

A brilliant disquisition on the essay form, that successfully sidesteps the pitfalls of that particular meta-form, which include banging on about Barthes, Montaigne and Sontag all the time, and coming across as immensely pleased with yourself. Thankfully, Dillon is as self-lacerating as he is intelligent, and this book (like The Dark Room, which I reviewed back in the day, and which Fitzcarraldo are bringing out in a new edition next year) is an acute piece of self-criticism, repeatedly backing into short, unexpected jolts of memoir. It also quotes one of my very favourite passages, from one of my very favourite books, something that made me shout with joy when I saw it.

The Red Parts: Autobiography of a Trial, by Maggie Nelson (Vintage)

I was blown away by The Argonauts when I read it last year, and so I leapt at the chance to read Bluets (2009) and The Red Parts (2007) when Vintage reissued them this year. Bluets I found a little dull (I wrote about it, sort of, here), but The Red Parts gripped me completely. It is Nelson’s account of the trial of Gary Earl Leiterman for the murder of Jane Mixer, Nelson’s mother’s sister, 36 years earlier. It is not a piece of true crime. It is an investigation of various emotional states, and of the ability of writing to capture these, and the risks involved in this. It had me thinking about James Ellroy (whom I used to read a lot) long before Nelson lays into him, decisively. This isn’t quite as mind-shifting as The Argonauts, and it does make me wonder what Nelson will write next. She has a lot to live up to.

After Kathy Acker, by Chris Kraus (Allen Lane)

A third biography in my selection: I seem to be conforming to the stereotype of the reader who drifts from novel-reading to biographies as they age. Why? Well, because, knowing more of the world, you are more able to measure non-fiction against it; and because what comes naturally as a teenager and young adult – imagining yourself into the character of any protagonist – becomes harder as you see how options fall away from around you the further through life you go. I am not particularly interested in Acker as a writer – I tried reading Blood and Guts in High School, sent to me alongside a proof of this biography, and found it pretty repulsive, to be honest. But clearly she was an interesting person, and sometimes the price of learning about and understanding interesting people, and their place in the culture, is reading their books. After all, at the time when Acker was doing the interesting things she did (which included writing books whose interest lay elsewhere than in what they were actually saying), there was no Kraus to write about her. Now there is, and Kraus proves herself an admirable biographer. Parts of I Love Dick were rather heavy on the critical theory, but she is clear about Acker’s dalliance with theory what she brings to bear on Acker, in London, LA and New York, is always clear, always credible. She is also generous with her attention, looking, as does Darrieussecq in her book about Modersohn-Becker, to the partners of important artists, when their work has sometimes been unjustly overshadowed.

The Proof, by César Aira, translated by Nick Caistor (And Other Stories)

This is the third Aira that I’ve tried, and the first one that really clicked. I’m beginning to appreciate his modus operandi – partly thanks to a great interview in The White Review (No. 18). But still it’s hard to align his immense prolificness and imagination to the paradigm of modern publishing. Yes, Simenon wrote a hell of a lot, but with Simenon you knew what you were getting. The hit rate here seems less sure. But there is something so blissfully uninhibited about this short narrative, with its sexy, punky intro and its ascent into glorious, excessive violence, that makes perfect sense.

small white monkeys, by Sophie Collins (Book Works)

I’ve amended this post to make this an actual eleventh book of the year, rather than an addendum. It’s a brilliant, forthright essay about shame written by Collins (primarily a poet; she was in the first of the Penguin New Poets series earlier this year alongside Emily Berry and Anne Carson) as part of a project undertaken at the Glasgow Women’s Library. I bought it online directly after reading an extract published on the White Review website. Read that, and you might do the same.

(The pamphlet visible to the right is ‘Spring Sleepers’ by Kyoto Yoshida, one of a series of new stories from Stranger’s Press, a new publishing project from UEA. Beautifully produced, and some really intriguing stories.)

Today’s sermon: Blue, blue, blue, blue

I somehow seem to have acquired a number of books about the colour blue. When Vintage added to these with their reissue of Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, I decided I just had to write something about them. So, a piece about books about blue, by someone with, actually, no interest in the colour blue at all.

Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, originally published in the US in 2009 and only now appearing in the UK, thanks to Jonathan Cape, joins a small collection of books I seem to have acquired, without really trying, on the subject of the colour blue. Nelson’s book might best be described as an essay in the form of prose-poetic fragments; its tone is set from the first line, which runs: “Suppose I was to begin by saying that I had fallen in love with a color”. What follows are ruminations on Nelson’s relationship with the colour blue; more critical explorations of why this colour might have a power over us that red, for instance, or green don’t have; and brief back-slips into memoir that exhibit the same jagged candour as The Argonauts (2015).

The other books in my micro-collection are William Gass’s On Being Blue, Derek Jarman’s Blue, and Blue Mythologies by Carol Mavor. It may be chance that these particular books have come into my possession (I have no particular interest in the colour, myself) but it is surely not chance that all these books were written about blue, rather than any other colour. Nelson is well aware of the anomaly. “It does not really bother me that half the adults in the Western world also love blue”, she writes, “or that every dozen years or so someone feels compelled to write a book about it.”