Tagged: Teju Cole

Books of the Year 2023

As for the last few years, I’m reading fewer new books, in part as my university teaching replaces book reviewing as the driver of much of my ‘strategic’ reading, and in part perhaps because of my continued and always-belated attempted to catch up with unread classics (2023: War and Peace; 2022: Moby-Dick, Ulysses, Anna Karenina; 2019-20: In Search of Lost Time; Middlemarch; 2024? I’m not sure yet…)

Anyway, here are my ‘books of the year’ – I’m keeping the title for consistency’s sake, though really this is intended as a record of my reading. In 2023, as I’ve done in some of my previous years, I kept a ‘reading thread’, which migrated halfway through the year from Twitter/X to Bluesky. (I’m keeping my X account live, really just for the purposes of promoting A Personal Anthology; I’ve deleted it from my phone, and carry on my book conversations now on Bluesky). I’m grouped the books according to i) new books, i.e. published in 2023 ii) books read by authors who died in 2023 iii) other books, with a full list at the end.

Best new books

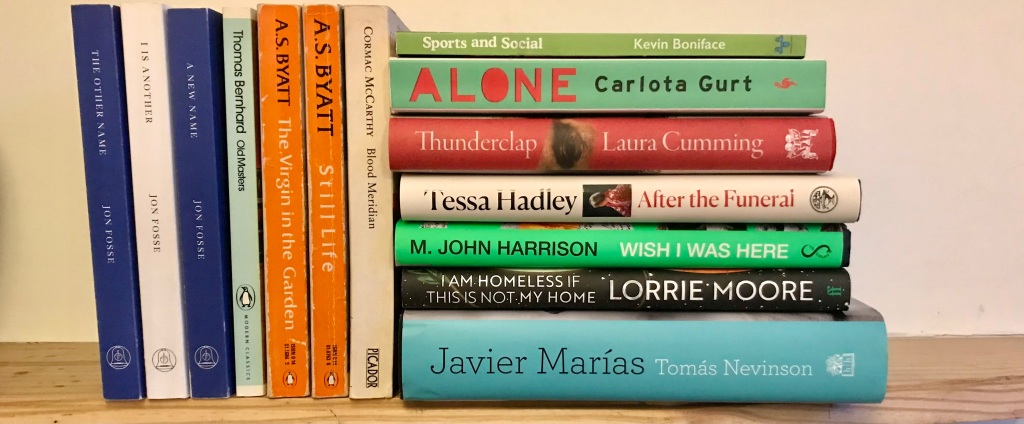

After the Funeral by Tessa Hadley was my book of the year. She is truly a contemporary master of the short story. I delight in her rich use of language, in her ability to draw me into characters’ lives and particular perspectives (though I’m aware that, in broad sociological terms, those characters are very much like me) and in the power and deftness with which she manipulates the narrative possibilities of the short story. She’s like an osteopath, who starts off gently – you think you’re getting a massage; you feel good; you feel in good hands – but then she does something more dramatic, leaning in and applying leverage, and you feel something shift, that you didn’t know was there. ‘After the Funeral’ and ‘Funny Little Snake’ are both brilliant stories well deserving of their publication in The New Yorker. ‘Coda’ is something else: it feels more personal (though I’ve got no proof that it is), more like a piece of memoir disguised as fiction, which is not really a mode I associated with Hadley. I read or reread all her previous collections in preparation for a review of this, her fifth, for a review in the TLS, and I have to say: there would be no more pleasurable job that editing her Selected Stories – the collections all have some absolute bangers in them – though equally I’d be fascinated to see which ones she herself would pick.

Tomás Nevinson by Javier Marías, translated by Margaret Jull Costa. Not a top-notch Marías, but a solid one: Nevinson is a classic Marías sort-of-spook charged with tracking down and identifying a woman in a small Spanish town who might be a sleeper terrorist, from three possible targets, which naturally involves getting close to and even sleeping with them. I found some of the prose grating – flabbergastingly so for this writer (“we immediately began snogging and touching each other up” – I mean, come on!) – but the precision of the novel’s ethical architecture is absolutely characteristic.

Alone by Carlota Gurt, translated by Adrian Nathan West. A compelling and moving Catalunyan novel about the stupidity of thinking you can sort your life out by relocating to the country. Similar in theme to another book I read this year (Mattieu Simard’s The Country Will Bring Us No Peace) though I liked that one far less. I won’t say much about it as I read it without preconceptions and recommend it on the same terms. I will say it reminded me of The Detour by Gerbrand Bakker, which is another novel of solitude and the land, which again benefits from stepping into as into an unknown locality.

I am Homeless if This is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore. Oh boy. I love love love Moore at her best and though this aggravated as much as delighted me it’s been nagging me ever since I really want to go back and read again. [NB I have gone back to it, as my first book of 2024, and am being far less aggravated than on the first read). After a brisk, unexpected and exhilarating opening the novel seems to go into stasis, a slow series of disintegrating loops. It fails to do the thing that Moore usually seems to do quite effortlessly: keep you dizzily engaged with a cavalcade of daft gags and darkly sly sharper wit and observation. The protagonist, Finn, seems to miss what Moore usually gives her central characters: a dopey friend to dopily muddle through life with. He has a brother, Max, but he’s dying, and an ex, Lily, who, well… But all of this is done in flat dialogue wrestling with the big questions. Moore usually lets the big questions bubble up from under the tawdry minutiae of life (as, brilliantly, in A Gate at the Stairs); here, they’re front and centre. More tawdry minutiae, I say! I think part of my frustration with the novel comes from a place of ‘Creative Writing pedagogy’. Wouldn’t it be better, I think, to open up Finn’s character, show him as a teacher, his banter with the students, and his entanglement with the head’s wife? Rather than making all of that backstory, dumping it into reflection. The scene with Sigrid, for instance – her attempts to flirt with Finn – would be stronger if we’d already met her in the novel, already seen their relationship (such as it is) in action. You tell students, first you establish the ‘normal’ of the protagonist’s existence, then you throw it into confusion. So, am I giving LOORIE MOORE MA-level feedback? Well, yes. To which the response (beyond: “she’s LORRIE MOORE”) is: she’s not writing that kind of ‘normal’ novel. For every bit of LM brilliance (the gravestone reading “WELL, THAT WAS WEIRD”; the line “Death had improved her French”) there’s something off, that should or could be fixed or cut: the cat basket sliding around on the car backseat; the scene where Finn’s car spins off the road.

A Thread of Violence by Mark O’Connell. A suavely written book that digs into the true crime genre but stops short of the moral reckoning it at least flirts with: that in truth it shouldn’t exist – as a published book, at least. Will surely sit on reading lists of creative non-fiction in the future.

Tremor by Teju Cole. Read quickly and carefully (in physical not mental terms: it was bought as a Christmas present and sneakily read before being wrapped up and given ‘as new’), with the full intention of going back and reading it again. Cole is a literary intelligence for our times, that I’d drop into the Venn diagram of the contested term ‘autofiction’, not for its supposed relationship to the author’s life, but for its relation to the essay form.

Wish I Was Here by M. John Harrison. In fact I haven’t finished reading this. But I dug what I read, and will go back and finish it, but feel like I wasn’t in the right headspace for it at the time. It’s a book to sit with, to scribble on, to squint, to make work on the page. It’s not a book to do anything as basic as just read.

Sports and Social by Kevin Boniface. Stories from the master of quotidian observation that somehow avoids observational whimsy (the curse of stand-up comedy). If we build a new Voyager probe any time soon this should be on it, but failing that I’d recommend putting a copy in a shoebox and burying it in your garden, for future generations to find.

Thunderclap by Laura Cumming. A slight cheat, as I finished this on the first of January 2024. But it was a Christmas present and perfectly suited the slow, thoughtful last week of the ending year. I loved Cumming’s take on Dutch art, and how its thingness is often overlooked, and I loved the way she mixed together scraps of biography of Carel Fabritius (about whom little is known) and a memoir of her father (James Cumming, about whom little is known to me). The fragments hold each other in tension very well, but it’s not fragments for fragments’ sake. Cumming delineates a space for thinking about art, and its relationship to life, and lives, and other elements, big and small: death, sight-loss, colour-blindness, the nature of explosions, dreams, more. Tension’s not the word: it’s more like a provisional cosmology, that puts thematic and informational pieces in orbit around each other. There’s no symphonic tying-together at the end, but things are allowed back in, with new things too.

I only started underlining (in pencil: it’s a beautiful book!) towards the end. Here are some lines:

- “Open a door and the mind immediately seeks the window in the room”

- “Painting’s magnificent availability”

- Of an explosion witnessed first-hand: “a sudden nameless sound […] a strange pale rain”

There is so little known about Fabritius, with so many of his paintings lost, but really there’s so little known about any of us, the book suggests… and most of our paintings will be lost (as paintings by Cumming’s father have already been lost) but yet looking at art brings a special kind of knowledge, showing us “the intimate mind” of the artist, as of a novelist, or – as here – a writer. The love of art and of life shines through, or not shines, but diffuses, as in one of the grey Dutch skies Cummings writes about.

“But I have looked at art” she says, and she shares that looking (as does T. J. Clarke in his magnificent The Sight of Death) but she also opens up a space for looking. If “But I have looked at art” is an understatement, a compelling gesture of humility, then Cumming can also write, again towards the very end of the book, “What a glorious thing is humanity” and not have it jar, or smack of pomposity. There is much to cherish – much humanity (and what else is there in the world truly to cherish? – in Thunderclap.

Continue readingA new #twitterfiction story: Train Day-Dreams @Wednesday3til5

Last year I wrote a short story on Twitter, a tweet a day. You can read about it here, and read it here.

Last year I wrote a short story on Twitter, a tweet a day. You can read about it here, and read it here.

This year, I have a different experiment I’d like to try on Twitter. What I’ve noticed is that some of the most interesting attempts to write creatively on the medium have come not ambiently (as ‘J’ was intended to do), but in sudden bursts – I’m thinking of Teju Cole‘s older and more recent excursions, and George Szirtes’ various entries in the form and Paraic O’Donnell, who occasionally goes into a riff on a Friday evening.

So I wanted to pick a time every week when I would tweet a story, or a something, and I settled on Wednesday afternoons, from 3-5pm, when – starting next week and for 10 weeks after – I will be always in the same place: sitting on a train from Norwich to London. It’s a train journey I love, for various reasons that may or may not become apparent during the course of the exercise, which will be over by April.

So, if you want to be in on the experiment, please follow @Wednesday3til5 – it is a new Twitter account I have set up, on which I will tweet only during those hours. What it will be exactly is still brewing, and will almost certainly be semi-improvised, at any rate.

Follow it, and something will unfold – I’m not going to guarantee how many tweets during those two hours each week, but clearly I don’t want it to be so many that you’ll want to unfollow.

What is a ‘chapter’ anyway? Reading Natsume Sōseki’s Kokoro – now with answers

I was inspired by a tweet from Niven Govinden (who’s reading his The Gate) to put down The Magic Mountain (it will wait for me) and pick up Natsume Sōseki’s Kokoro, as recommended to me by David Hayden, when I mentioned how much I loved Kusamakura, probably the best known of this Meiji-era Japanese novelist’s books.

I am enjoying Kokoro, which is the story of the friendship between a young and an old man, but one thing is confusing, or annoying, me. The novel (234pp in its elegant Penguin Classics edition, not counting introduction etc) is divided up into 110 chapters, the vast majority of which – do the maths – are two pages long.

Despite their brevity, the chapters are often not self-contained, but some four or five of them may cover the same scene, and run directly on from one to the next. As an extreme example, here is the end of Chapter 26 and the beginning of Chapter 27, during which the narrator and ‘Sensei’, as he calls his friend, are sitting in a garden, talking. Continue reading

Carly: A collaborative Twitter story

I have just finished running a Creative Writing workshop as part of the LSE’s Literature Festival 2013. In it I wanted to talk about and explore ways of using Twitter creatively. Briefly, I went through four ways of doing so:

1) the standalone one-Tweet narrative, as seen on nanoism.net. This, we found, was hard.

2) we looked at iterative tweets: those that set up parameters and worked within them, in a non-narrative way. I gave as examples the drone stories of Teju Cole, New Proverbs of Hell by George Szirtes, and some dialogue between W and Lars by Lars Iyer – and clicking on their names here will link to a few examples of each I collected via Storify.

I then asked people to tweet, beginning with either ‘I remember’ or ‘Last night’ (using the #lsefiction hashtag) and I collected these in Storify here and here

3) we looked at narrative stories on Twitter, Jennifer Egan’s Black Box, Rick Moody’s Some Contemporary Characters, Andrew Fitzgerald’s March story on Medium and Litro’s recent #litrostory – which I contributed to, and may have inadvertently damaged – honestly, Litro people, I thought I was bringing the story back to its main narrative. (I also talked about my own Twitter story, J, which you can read more about here, and follow here.)

In fact, the #litrostory – as i saw it – was instructive, because it showed the pitfalls of open sourcing a project like this. People don’t read up what’s gone before, they push it in odd directions, they might even change tense or gender. I wanted to do something a bit like this, but a bit more curated, so as the final exercise we wrote a collaborative piece of non-narrative fiction, a character study, really, called Carly. This was number four. Continue reading

April reading: Josipovici, Cole, Vila-Matas, Enright, Hardwick

The job of retracing my reading over a month is a strange one, involving pulling out the books from the shelves where – hopefully – they’ve found their way, so as to make room for the current mess. Some of April’s reading I’ve already written about – Enrique Vila-Matas’s wonderful Dublinesque (the best book of his I’ve read so far, and certainly the one you would hope will broaden his English language readership) and Umberto Eco and Jean-Claude Carrière’s brassily erudite conversation piece This is not the End of the Book in a blog post here, to which I added a footnote concerning Teju Cole’s quietly, devastatingly manipulative Open City; and Chris Bachelder’s Abbott Awaits, the book all liberal-minded dads should carry slotted down the back of their Baby Bjorns, celebrated here.

Looking back at books over the chasm of a few weeks, rather than writing about them hot off the last page, means interrogating your reading self to see what remains of the experience: Gabriel Josipovici’s Only Joking, for instance, seems now an unforgivable diversion, a modernist skit on the caper movie that evaporates from the page, leaving no real sediment to speak of. It is a comedy, told largely in dialogue, about a series of variously wealthy, artistic, ingenious and criminal types all trying to do each other over for the sake of a Braque painting, or love, or neither. It entertains, but less than Charade, or Len Deighton in Only When I Larf mode.

Looking back at books over the chasm of a few weeks, rather than writing about them hot off the last page, means interrogating your reading self to see what remains of the experience: Gabriel Josipovici’s Only Joking, for instance, seems now an unforgivable diversion, a modernist skit on the caper movie that evaporates from the page, leaving no real sediment to speak of. It is a comedy, told largely in dialogue, about a series of variously wealthy, artistic, ingenious and criminal types all trying to do each other over for the sake of a Braque painting, or love, or neither. It entertains, but less than Charade, or Len Deighton in Only When I Larf mode.

The other thing that occurred to me over and over again as I read April’s books, is how wonderful it is to read books in tandem, or close enough to each other that it feels like it. The Vila-Matas and the Eco/Carrière, as I blogged, seemed in direct conversation with each other about the vitality of the physical book, but then there’s Teju Cole and WG Sebald, whose Rings of Saturn I am still re-reading, slow-slow-slowly. Continue reading

Just in case the book dies before I get back from New York

A rushed post, while the kids watch the Simpsons, and before I go upstairs to pack to fly to New York tomorrow. These last couple of days I’ve been trying to finish these two books, which arrived over the weekend, and which I’ve been reading in alternation, Dublinesque, the new novel by Enrique Vila-Matas, author of the wonderful Montano (here’s my Indy review, here’s Lars Iyer’s manifesto, which treats it at more length), and This is Not the End of the Book, a transcription of some characteristically wide-ranging and ebullient conversations between Umberto Eco and Jean-Claude Carrière.

Quite apart from the resonance of the Vila-Matas to my first trip to New York, of which more below, the two books play off each other through their shared theme of the death, or otherwise, of the book, or literature. In fact, they are almost as much in dialogue with each other as are UE and J-CC in TINTEOTB (an abbreviation which brings to mind both Tintin and Kinbote, the mad editor of Pale Fire).

Quite apart from the resonance of the Vila-Matas to my first trip to New York, of which more below, the two books play off each other through their shared theme of the death, or otherwise, of the book, or literature. In fact, they are almost as much in dialogue with each other as are UE and J-CC in TINTEOTB (an abbreviation which brings to mind both Tintin and Kinbote, the mad editor of Pale Fire).

The Eco/Carrière, as its title suggests, is a repudiation of the idea that the book is going to be killed by the digital revolution Continue reading