Tagged: James Joyce

Books of the Year 2022

Reading habits and outcomes change according to personal inclination, of course, but also according to external factors: life circumstances, temperament and age, the demands of a job. All of which is to say I’ve read fewer new books this year than in the past. I review less than I used to, certainly, and when I read for work (teaching Creative Writing at City, University of London) I’m more interested in the books that came out a year or two ago, and that have perhaps started to settle into continued relevance, than the whizz-bang must-read of the year.

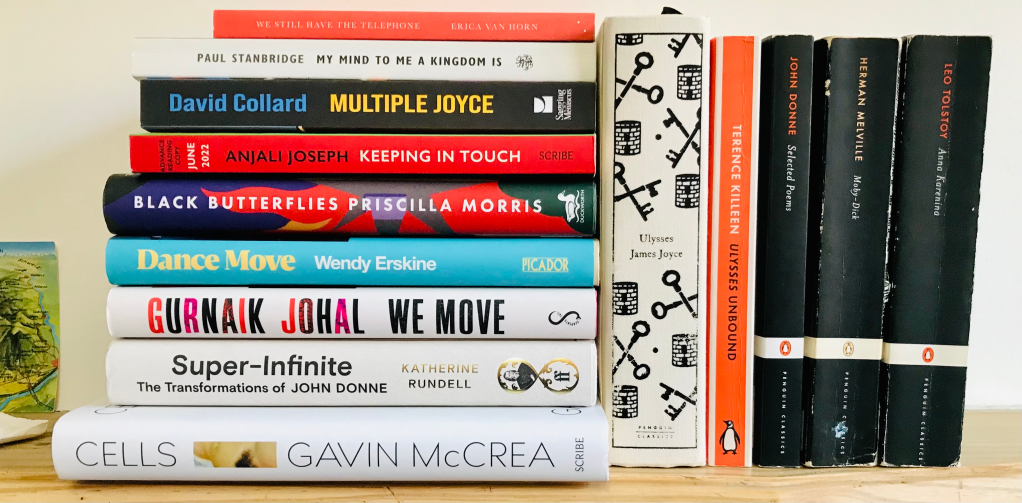

Of the new books I have read, that have made a lasting impression, here are seven:

Ghost Signs by Stu Hennigan (Bluemoose) is an unforgettable journal of the 2020 Covid pandemic lockdown, during which the author was furloughed from his job working for Leeds City Council libraries and volunteered to deliver food parcels to vulnerable people and families. The eerie descriptions of empty motorways and fearful faces peering round front doors evoke that weird time in 2020, but the true and lasting impact of the book comes from Hennigan’s realisation that the poverty and distress he discovers in his adopted city isn’t down to the pandemic at all, but to entrenched government policies that have forced council services to the brink, and thousands of people into shamefully desperate circumstances. It’s a political book, sure, but one written out of necessity, rather than out of desire or ideology, and one that you want every politician in the country to read, and quickly, so that the responsibility for dealing with the issues it raises passes to them, rather than resting with Hennigan. (That’s the problem with writing books like this, isn’t it? That by being the person who identifies or expresses the problem, you become inextricably linked to it, a spokesperson, a talking head, with all the emotional labour that implies.)

(Ghost Signs isn’t in the photo because I’ve given away or lent both copies I’ve owned.)

I heard Hennigan read from and talk about the book at The Social in Little Portland Street, London this year, and the same goes for Wendy Erskine, who was promoting her second collection of short stories, Dance Move (Picador). Erskine is one of the most talented short story writers in Britain and Ireland today, and I’ll read pretty much anything she writes. Dance Move is at least as good as her first collection, Sweet Home, and if you made me choose I’d say it’s better. The stories are muscly, chewy. Erskine has had to wrestle with them, you can tell. They are worked. She takes ordinary characters and by introducing some element that might be plot, but isn’t quite, she forces their ordinary lives into unprecedented but gruesomely believable shapes. These stories are perfect examples of the idea that plot and dramatic incident should be at once surprising and inevitable. But the thing I love most about her stories (I wrote a blog post about it here) is how she ends them:

You are so immersed in these characters’ lives that you want to stay with them, but the deftness of the narrative interventions means that the stories aren’t wedded to plot, so can’t end with a traditional narrative climax or denouement.

(As David Collard said, in response to my original tweets, “Wendy Erskine’s stories don’t end, they simply stop” – which is so true. Perhaps it would be even better to say, they don’t finish, they simply stop.)

So how does she end them? She kind of twists up out of them, steps out of them as you might step out of a dress, leaving it rumpled on the floor. In a way that’s the true ‘dance move’: the ability to leave the dance floor, mid-song, and leave the dance still going.

Take the story ‘Golem’, definitely one of my favourites in the collection. It’s a story that does everything Erskine’s stories do. It densely inhabits its characters’ lives, and it has its comic-surreal interior moments, but most incredibly of all, it manages to end at the perfect unexpected moment. The story goes on, but the narrative of it ends. It departs, exits the room, taking us with it.

Perhaps the best way to put it is that you feel that, yes, the characters are ready to live on, and yes, you’d be ready to keep on reading the prose and the dialogue forever, but no, you wouldn’t want the stories themselves to last a single sentence longer.

My other favourite short story collection of the year is We Move by Gurnaik Johal (Serpent’s Tail), which is a thoroughly impressive debut, that again seems to show how short stories can be the perfect receptacle for characters: they give us characters, rather than plot, rather even than writing, or prose, or words. The difference between this and Dance Move is that We Move, to an extent, looks like the traditional debut-collection-as-novelist’s-calling-card. I’d love to read a novel by Johal – or for Erskine, for that matter, but equally I’d love her to just go on writing stories, because the more people like her keep writing stories, rather than novels, the stronger and more vital the contemporary short story as form will be.

My Mind to Me A Kingdom Is by Paul Stanbridge (Galley Beggar – publisher of my debut novel, though I don’t know Paul) is an exquisite piece of writing that does live or die by its sentences. (Narrator: it lives). An account of the aftermath of the author’s brother, it is indebted to WG Sebald, in terms of the way it leans on and deals out its gleanings of learning, but also in terms of how its lugubriousness slides at times into a form of humour, or perhaps of playfulness. No mean feat when you’re writing about a sibling who killed himself. A hypnotising read.

My most unexpectedly favourite book of the year was Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne, by Katherine Rundell (Faber), which I wrote about for The Lonely Crowd, here. I didn’t know I needed a biography of a Sixteenth Century English Metaphysical poet in my life, but Rundell fairly grabs your lapels and insists you read him. Frankly I’d read any book that contains lines like “A hat big enough to sail a cat in” and “joy so violent it kicks the metal out of your knees, and sorrow large enough to eat you” in it.

My final new book of the year is We Still Have the Telephone by Erica van Horn (Les Fugitives), which I received as a part of a support-the-publisher subscription. It’s a delightfully sly and spare account of the author’s relationship with her mother. “My mother and I have been writing her obituary” etc. One to file alongside Nicholas Royle’s Mother: A Memoir, and Nathalie Léger’s trilogy of Exposition, Suite for Barbara Loden and The White Dress (also from Les Fugitives) as great recent books about mother-child relationships.

A mention here too for Reverse Engineering (Scratch Books) which is a great idea: a selection of recent short stories accompanied by short craft interviews with their authors. It’s got succeed on two levels: the stories themselves have to be worth reading, and the interviews have got to add something more. It succeeds on both, with wonderful stories from some of our best contemporary story writers: Sarah Hall (at her best the best contemporary British short story writer), Irenosen Okojie, Jon McGregor, Chris Power, Jessie Greengrass etc, and useful commentary. I look forward to reading more in the series.

(Copy not shown in photo as loaned out.)

I’ll include another section here on new books, but new books written by writer friends or colleagues: Cells by Gavin McCrea (Scribe) is a jaw-droppingly raw and honest memoir that bristles with insight, and revelation, and liquid prose. Keeping in Touch (also Scribe) is my favourite yet of Anjali Joseph’s novels, a properly grown-up rom-sometimes-com, that makes you want to get on airplanes, travel the world, travel your own country, wherever that is, talk to people, work people out, and fall in love, which is perhaps the same thing. And Black Butterflies by Priscilla Morris (Duckworth) is a novel I’ve been waiting more than a decade to read, and it didn’t disappoint. It’s a moving and delicate told narrative of the siege of Sarajevo, that perhaps wasn’t best served by its publication date just as something horribly similar was happening in and to Ukraine. Finally, 99 Interruptions is the latest slim missive from Charles Boyle, who published my Covid poem Spring Journal in his CB Editions. It sits alongside his pseudonymous By the Same Author as a perfect short book – with the same proviso that it’s so damned slim that it’s easy to lose. And indeed barely a month after buying it I already can’t find it to put in the photo. No matter. I’ll find it, months or years hence, by accident, and enjoy rereading it all the more for that.

For various reasons, this was a strong year for me for successfully finishing fat chunky classics that I’d tried and failed to read in the past: the kind of book I usually can’t read unless I can organise my life around it.

Continue readingInstead of June reading 2021: the fragmentary vs the one-paragraph text – Riviere, Hazzard, Offill, Lockwood, Ellmann, Markson, Énard etc etc

This isn’t really going to function as a ‘What I read this month’ post, in part because I haven’t read many books right through. (Lots of scattered reading as preparation for next academic year. Lots of fragmentary DeLillo for an academic chapter I filed today, yay!)

Instead I’m going to focus on a couple of the books I read this month, and others like them: Weather by Jenny Offill, and Dead Souls, by Sam Riviere. I wrote about the fragmentary nature of Offill’s writing last month, when I reread her Dept. of Speculation after reading Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This (the month before), all three books written or at least presented in isolated paragraphs, with often no great through-flow of narrative or logic to carry you from paragraph to paragraph.

Riviere’s novel, by contrast, is written in a single 300-page paragraph, albeit in carefully constructed and easy-to-parse sentences. And, as it happens, I’ve just picked up another new novel written in a single paragraph – this one in fact in a single sentence: Lorem Ipsum by Oli Hazzard. I haven’t finished it, but it helped focus some thoughts that I’ll try to get down now. These will be rough, and provisional.

Questions (not yet all answered):

- What does it mean to present a text as isolated paragraphs, or as one unbroken paragraph?

- Is it coincidence that these various books turned up at the same time?

- Does it tell us something about ambitions or intentions of writers just now?

- Are fragmentary and single-par forms in fact opposite, and pulling in different directions?

- If they are, does that signify a move away from the centre ground? If not, what joins them?

Let’s pull together the examples that spring to mind, or from my shelves:

Recent fragmentary narratives:

- No One is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood (2021)

- Weather (2020) and Dept. of Speculation (2014) by Jenny Offill

- Assembly by Natasha Brown (2021) – in part, it jumps around, I haven’t read much of it yet.

And further back;

- This is the Place to Be by Lara Pawson (2016) A brilliant memoir written in block paragraphs, but allowing for a certain ‘through-flow’ of idea and argument.

- This is Memorial Device by David Keenan (2017) – normal-length (mostly longish) paragraphs, but separated by line breaks, rather than indented.

- Satin Island by Tom McCarthy (2015) – a series of long-ish numbered paragraphs, separated by line breaks.

- Unmastered by Katherine Angel (2012) – fragmentary aphoristic non-fiction, not strictly speaking narrative.

- Various late novels by David Markson, from Wittgenstein’s Mistress onwards

- Tristano by Nanni Balestrini (1966 and 2014) – a novel of fragmentary identically-sized paragraphs, randomly ordered, two to a page. The paragraphs are separated by line breaks, but my guess is that the randomness drives the presentation on the page.

Recent all-in-one-paragraph narratives:

- Lorem Ipsum by Oli Hazzard (2021)

- Dead Souls by Sam Riviere (2021)

- Ducks, Newburyport by Lucy Ellmann (2019)

And further back:

- Zone (2008) and Compass (2015) by Mathias Énard

- Various novels by László Krasznahorkai, of which I’ve only read Satantango (1985) – a series of single-paragraph chapters.

- Various novels by Thomas Bernhard, of which I’ve only read Correction (1975) and Concrete (1982)

- The first chapter of Beckett’s Molloy (1950) is a single paragraph, as is the last nine tenths of The Unnameable(1952)

- The final section of Ulysses, by James Joyce (1922)

So, my thoughts:

Continue readingApril Reading 2020 Part 2: More Proust

Part One of my April 2020 Reading blog post covered the essays of Lydia Davis and Natalia Ginzburg. Read it here.

Apart from Ana María Matute’s The Island (reviewed here) the only other book I finished in its entirety in April was, I think, Sodom and Gomorrah, the fourth volume of Proust. I started reading Proust last year, as my 2019 New Year’s Resolution, but stalled after finishing the third volume on my summer holiday. By October I’d abandoned the fourth volume. (I’ve been dating the passage where I leave off each day, as well as posting notes on another Twitter account, @ProustDiary.) I picked the fourth volume back up in March of this year, and finished it in April. I am now most of the way through the fifth volume, The Prisoner.

So: I am making good progress, but in fact lockdown hasn’t given me that much more time to read than normal. It’s not just that I am working, from home, but that reading, in a busy house of five people (two adults and three teenage boys) can sometimes be a hard activity to justify. Sitting with a laptop is work. Sitting in front of the television is generally a communal activity, and one that can bring the family together outside of mealtimes in a way that board games and jigsaws, because of particular personality types, can’t always do. Reading, apart from at bedtime, is likely to get you looked at strangely – more strangely, I’m afraid to say, than looking at your phone.

I have been enjoying Proust very much in parts, and drifting through others. Indeed, I felt particularly skewered by this aside in Nabokov’s Lectures on Literature:

To a superficial reader of Proust’s work – rather a contradiction in terms, since a superficial reader will get so bored, so engulfed in his own yawns, that he will never finish the book – to an inexperienced reader, let us say…

So let’s call me an inexperienced reader. Certainly, there have been plenty of bits where I have been bored, and irritated. Irritated by the fascination with the workings of society, and bored by the endless unfoldings, like a piece of eternal fractal origami, of the intricate inner imbrications of sometimes mundane psychological impulses. More on this later. Continue reading

On being two years older than Leopold Bloom

It was as I was listening to BBC Radio 4’s 1993 ‘dramatisation’ of Ulysses last week that it hit me.

I had been listening as I worked – mindless computer work – and the quasi-ambient experience, with only half of my attention devoted to the audiobook, seemed rather to suit its style: protean, contingent and demotic. Its tide of impressions, internal and external, washed over me and back, and occasionally I had to pause the file, and drag back to a listen to a moment again.

But, when Molly Bloom, near the start of her soliloquy (beautifully performed by Sínead Cusack), said “getting on to forty he is now” I had to actually get up and physically fetch my copy of the book to check it.

What the fuck: Leopold Bloom is under forty?

What the double fuck: He’s younger than me?

This astonishing fact went against my most basic, never-articulated assumptions about the book. Frankly, it got me down. Continue reading