‘After my own heart’: an occasional post after Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence

I was reading Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence last night, in the way that you’re supposed to, dipping into it, looking for something to snag my interest – either the writer of the sentence in question, or the sentence itself, or something Dillon might have to say – and I alighted on his section on Elizabeth Bowen, whose stories I also happen to haphazardly reading at the moment, because I’m reading Tessa Hadley’s stories, Hadley being a fan and literary descendent of sorts of Bowen… and, anyway, I read this passage:

As I write, I’m two thirds of the way through A Time in Rome, which [Bowen] published in 1960, and I think I have found, again, a writer after my own heart. How many times does it happen, dare it happen, in a life of reading? A dozen, maybe? There is a difference between the writers you can read and admire all your life, and the others, the voices for whom you feel some more intimate affinity. Could Elizabeth Bowen be turning swiftly into one of the latter, on account of her amazing sentences?

Which is marvellous, and sparked two particular thoughts, last night, and has sparked a couple more, this morning, as I sit down to write, on a Bank Holiday Sunday morning, at just gone 8am. There’s one, on the phrase “after my own heart”, that I really want to get to, so I’ll try to dispatch the other ones briefly.

Firstly, the word ‘affinity’, which is obviously an important word for Dillon: it was the name of Dillon’s next book, after all. It could just as easily have been the title of this one. What interests me about the word, however, is its aura of neutrality. When we think of the connections that get built between – as here – us as individual readers, and particular writers, we tend to look to one or the other as the active agent in the relationship. Either the writer is a genius – they seduce me, impress or overawe me – or I love the writer, I find something particular in them. But an affinity is bipartisan, and objective, as if unwilled by either. The chemical usage of the word is the most critically productive one, especially after Goethe applied it to human relationships in Elective Affinities, but in fact the original meaning was to do with relationships – in particular relationships not linked by blood, such as marriage, or god-parentship. I suppose, contra Goethe, what I like about the term is that these affinities that Dillon is talking about seem to be un- or non-elective, but weirdly, inexorably fated.

(NB I haven’t read Affinities yet, so maybe Dillon goes into all this in his book.)

The other brief thought from this morning was that, although Dillon does talk about Bowen’s fiction in his piece on her, the sentence he picks to write about is from her sort-of-travel book A Time in Rome. And this made me think of the death, last week, of Martin Amis, and how much of the online critical chat had an undercurrent of favouring the non-fiction (the journalism, and the first memoir) over the fiction (with a few exceptions, usually involving Money), and I wondered if anyone had really considered, at length, the legacy of writers that had written both fiction and non-fiction, and what it meant when one was favoured over the other. Susan Sontag wanted to be remembered as a novelist, but isn’t, and won’t be. It would surely appal Amis if he felt that it was his book reviews and interviews that we remembered him for. Geoff Dyer does talk about this a bit with reference to Lawrence in Out of Sheer Rage, but I’d like to read something broader. If a writer has a style, and that style is to an extent consistent over their fiction and non-fiction, then what are the conditions by which they become remembered, and stay read, after their death, for one rather than the other? Or, alternatively, is there a difference in terms of how a similar style applies to fiction, and non-fiction?

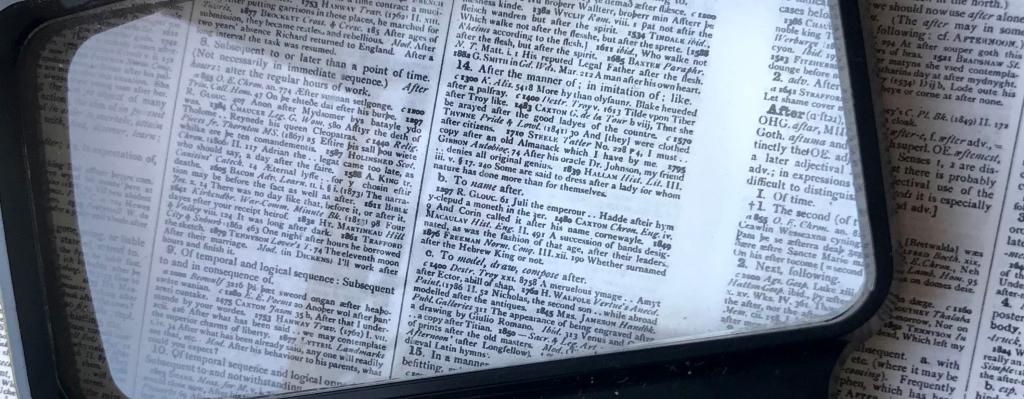

Now to the original point I wanted to make. Dillon’s paragraph on his relationship to Bowen is lovely, and I’m sure many readers will relate to it, as I did, but I was particularly struck by the phrase a writer after my own heart. “After my own heart” – it’s a strange and wonderful idiom, and sent me – it’s a Bank Holiday weekend – to the dictionary. ‘After’, after all, is a preposition that, like most prepositions, has a variety of different uses.

“After my own heart” could, for instance, have a sinister intent, as with hounds after a fox. The writer in pursuit of the reader’s heart. But it doesn’t mean that. It means “after the nature of; according to”, a usage going back to the Bible (“There is therefore now no condemnation to them which are in Christ Jesus, who walk not after the flesh, but after the Spirit”, Romans 8:1-2) – though the specific usage of “a man after his own heart” isn’t recorded until 1882, when it appears in, of all places, The Guardian, attributed to one G. Smith.

But the other meanings or uses of ‘after’ hover around the word. ‘After’, too, in the sense of “after the manner of; in imitation of”, as it’s used in art history – for example, Picasso’s The Maids of Honor (Las Meninas, after Velázquez). I remember a novel called After Breathless, by Jennifer Potter, that I read simply because it was inspired by A Bout de Souffle, my favourite film. “After my own heart” as critical interrogation.

And then the word ‘own’ in the phrase, too: after my own heart. It’s a phrase that is deeply, reverberantly embedded in the language from which it grows. It’s a phrase to conjure with. It’s an idiom, in other words.

My final brief thought, and again someone has probably written on this, but what exactly is the relationship between idiom and cliché? Does an idiom have to pass through the state of being a cliché before it can achieve this linguistic apotheosis? Is an idiom merely a cliché that has freed itself of the negative connotations of overuse – overuse with a single meaning – to allow itself to take on other meanings. Because that’s the problem with clichés, isn’t it? Not that they’re overfamiliar as phrases – as signifiers – but because their overuse has obliterated the meaning the phrase intends. The site of meaning has been rubbed raw.