Category: Monthly reading

Instead of June reading 2021: the fragmentary vs the one-paragraph text – Riviere, Hazzard, Offill, Lockwood, Ellmann, Markson, Énard etc etc

This isn’t really going to function as a ‘What I read this month’ post, in part because I haven’t read many books right through. (Lots of scattered reading as preparation for next academic year. Lots of fragmentary DeLillo for an academic chapter I filed today, yay!)

Instead I’m going to focus on a couple of the books I read this month, and others like them: Weather by Jenny Offill, and Dead Souls, by Sam Riviere. I wrote about the fragmentary nature of Offill’s writing last month, when I reread her Dept. of Speculation after reading Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This (the month before), all three books written or at least presented in isolated paragraphs, with often no great through-flow of narrative or logic to carry you from paragraph to paragraph.

Riviere’s novel, by contrast, is written in a single 300-page paragraph, albeit in carefully constructed and easy-to-parse sentences. And, as it happens, I’ve just picked up another new novel written in a single paragraph – this one in fact in a single sentence: Lorem Ipsum by Oli Hazzard. I haven’t finished it, but it helped focus some thoughts that I’ll try to get down now. These will be rough, and provisional.

Questions (not yet all answered):

- What does it mean to present a text as isolated paragraphs, or as one unbroken paragraph?

- Is it coincidence that these various books turned up at the same time?

- Does it tell us something about ambitions or intentions of writers just now?

- Are fragmentary and single-par forms in fact opposite, and pulling in different directions?

- If they are, does that signify a move away from the centre ground? If not, what joins them?

Let’s pull together the examples that spring to mind, or from my shelves:

Recent fragmentary narratives:

- No One is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood (2021)

- Weather (2020) and Dept. of Speculation (2014) by Jenny Offill

- Assembly by Natasha Brown (2021) – in part, it jumps around, I haven’t read much of it yet.

And further back;

- This is the Place to Be by Lara Pawson (2016) A brilliant memoir written in block paragraphs, but allowing for a certain ‘through-flow’ of idea and argument.

- This is Memorial Device by David Keenan (2017) – normal-length (mostly longish) paragraphs, but separated by line breaks, rather than indented.

- Satin Island by Tom McCarthy (2015) – a series of long-ish numbered paragraphs, separated by line breaks.

- Unmastered by Katherine Angel (2012) – fragmentary aphoristic non-fiction, not strictly speaking narrative.

- Various late novels by David Markson, from Wittgenstein’s Mistress onwards

- Tristano by Nanni Balestrini (1966 and 2014) – a novel of fragmentary identically-sized paragraphs, randomly ordered, two to a page. The paragraphs are separated by line breaks, but my guess is that the randomness drives the presentation on the page.

Recent all-in-one-paragraph narratives:

- Lorem Ipsum by Oli Hazzard (2021)

- Dead Souls by Sam Riviere (2021)

- Ducks, Newburyport by Lucy Ellmann (2019)

And further back:

- Zone (2008) and Compass (2015) by Mathias Énard

- Various novels by László Krasznahorkai, of which I’ve only read Satantango (1985) – a series of single-paragraph chapters.

- Various novels by Thomas Bernhard, of which I’ve only read Correction (1975) and Concrete (1982)

- The first chapter of Beckett’s Molloy (1950) is a single paragraph, as is the last nine tenths of The Unnameable(1952)

- The final section of Ulysses, by James Joyce (1922)

So, my thoughts:

Continue readingMay reading 2021: Offill, Machado, Murata, Slimani, Kristof, Spark

Seven books, mostly quite short. I re-read Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill for what was at least the third time. I think I picked it up as I’d been reminded of it by Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This, which I wrote about last month, and is written in a somewhat similar format. While the fragmentary form in Lockwood’s novel is clearly intended to represent consciousness fractured through Twitter and social media, Offill’s book is less online, and more about consciousness fractured through modern life in general. Offill is more constrained, more zen. The narrator’s brain has filtered the world. Lockwood’s narrator can’t filter the world, and insists on adding to it, interpreting it.

Lockwood’s book, as I said in my post, is unnerving, even enervating to read. Offill’s is restful, even when it turns dark.

Nevertheless, it’s odd that the book seems to lose its way after the halfway mark. It can’t do the melodrama it has promised, through its story of marital breakdown, but it performs a wonderfully neat pirouette to avoid the collision. This happens in the superb chapter 32, in which the narrator confronts her errant, adulterous husband and his ‘other woman’, but undermines her own description with a viciously precise creative writing commentary: “Needed? Can this be shown through gesture?”

The scene that follows reminded me of the equivalent one in Elena Ferrante’s Days of Abandonment. But, where that is brilliantly visceral, this one just crumbles. That said, I suppose the temporary ‘failure’ of the novel is justified by its premise. The narrator is somebody who needs to be in control. That’s what’s behind her compulsive marshalling of facts, which she parcels out in those fragmentary paragraphs. When she loses control, the narrative dissolves into a swamp of entropy and only gradually, and it’s not entirely clear how, works its way back out. She reads a self-help book about surviving adultery, which she sneers at, but which – maybe – helps.

For sure, this book is not a self-help book about fixing a collapsing relationship. For all the nuggets of wisdom it purportedly contains, it’s never clear how they do it, the two of them, the couple and their daughter, beyond moving to the country, the “geographic cure”, which seems a surprisingly old-fashioned resolution to such an untraditionally presented story.

It reminds me of one of my all-time favourite books: Wittgenstein’s Mistress by David Markson. Similar in the fragmentary form, similar in the obsessive relay of facts, and knowledge, and wisdom. (Rilke! The Voyager recording!) All of which is weaponised, and then irradiated. Literature as series of fortune cookies. Knowledge is reducible, and manageable, and transferable, and this is at once a good and a bad thing. (It reminds me, too, of Lucy Ellmann’s Ducks, Newburyport, which I never did/still haven’t finished.)

All three books, or four, counting Lockwood, though perhaps that one less, are about the uselessness of knowledge in the face of the world. Forgert Rilke, forget wisdom. If you want to save your marriage, simply move to the country, get a puppy, chop firewood. Which is lovely, but… really?

In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado is an eye-opening account of an abusive relationship that turns expectations of the sub-genre on their head. The formal invention is impressive and effective, but some things do get lost. The book is a persuasive account of a subjective experience – of being gaslit and abused – and what I missed as a reader was the objective dimension. The ‘woman in the dream house’ – the abuser – remains something of an enigma. What was she like? What was her problem? Of course, this lack, this absence, may well be partly due to the ethical and legal aspect of memoir writing. The ‘woman’ presumably must remain vague in some aspects so she remains unidentifiable, and can’t sue. (I covered some of this in my review of Deborah Levy’s Real Estate.) For all its inventiveness, the book delineates the limits of what memoir can do.

I enjoyed Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata, which I read after listening to Merve Emre and Elif Batuman discussing it on the Public Books podcast. I didn’t agree with everything they said, but I was intrigued in particular about their description of the book as ‘an adultery novel’, i.e. a story build on a simple narrative model of thesis – anthesis – synthesis. I was preparing a workshop on plot and structure in novel-writing (for London Writer’s Café, hopefully more to come in the Autumn!) and thought it would be interesting to see how the novel managed this.

Continue readingMarch & April Reading 2021: Lockwood, Moore (Lorrie), Levy, Moore (Susanna), Nelson, Garner, Hall, Musil

At the start of 2021 I began an open-ended Twitter thread listing and commenting on my reading as I finish each book. This was supposed to help with these monthly round-ups, to save time, which clearly didn’t work at the end of March, as I didn’t post a round-up at all. So, for this two-month round-up I’ll be picking and choosing and expanding on those thoughts on some but not all of what I’ve read, rather than going through it doggedly.

It took me a bare couple of hours to read No One is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood, and I’ve spent at an hour elsewhere reading reviews and thinkpieces about it. Which only goes to show, as someone on here pointed out, that it’s the least well-titled book of the year. Unless she means it ironically. Or post-ironically. Or whatever.

I did really like the book, but also I found it exasperating and even anxiety-provoking. The short, fragmentary sections are clearly designed to mimic Twitter, but unlike Twitter you seem to have to read every one of them, as if there is something to ‘get’ from each of them.

This was confusing. On Twitter, after all, you skim through a dozen tweets in as many seconds before you deign to give one your more considered attention, sometimes scrolling back up to read one you initially skimmed over. Your micro-decisions about what to give your attention to are affected by names, and digital paratexts like avis and retweet and like counts. You don’t get that with tweet-length paragraphs on the page of Lockwood’s novel, but equally the usual narrative paraphernalia that allow you to speedily and efficiently navigate a story are also absent. Even Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation had more flow and propulsion across its narrative islets than this.

Of course you acclimatise, and for a while you drift through the novel, picking up little dopamine hits for identifying memes and moments. The incest advert. The plums poem. But the pace of reading picks up, and the drifting becomes sliding, and it takes a great line to slow you down. Thankfully there are plenty of great lines.

Then Something Happens, plot-wise, and this is where the real challenge for the novel lies. Having established a vehicle of utter affectlessness in the first half (even while critiquing and despairing over the same), can it step up and deal with a subject that demands genuine emotional engagement?

Well the answer is no, for me at least. The emotion is there, and if you’ve read the interviews and perhaps even if not you’ll know it’s real, but the novel simply cannot express it. None of the usual, traditional functional parts – the filters and switches – are present, or work as required. It’s as if the book knows it’s trapped, and wants to break out of the trap it’s built for itself – and that’s part of the project after all, that’s what so many of us want to know: is there a way through this way of being, that will lead to another, better one?

What’s missing is the connective tissue. Now, the online world, when we are in it, does contain a connective tissue, of sorts: what gets called ‘the discourse’ (as in: the discourse is particularly toxic this morning). The discourse is the suspension (in the scientific sense) in which the individual tweets float, and take their context, and to which they all, infinitesimally, add.

The point of the novel seems to be that this way of connecting with the world is leaving us adrift and unfulfilled. But when Lockwood gets to the second part of the novel, when tragedy drags her away from the Portal and immerses her in real life, the novel doesn’t change. It’s still written in that atomised, fragmentary style. Is that because this is the only way the narrator can think the world into being? Or is it intended to show the inability of ‘interneted narrative’ to represent the deep continuum of real life? Would it have been a failure of form if Lockwood had ‘reverted’ to a more traditional narrative style to cope with what happens ‘off-screen’?

No One is Talking About This is a tragedy of form, because although it allows me to empathise with the narrator when she is feeling sad about her unconnectedness, it fails to make me empathise when she suffers genuine tragedy. And it’s the form that engineers that failure.

Anagrams by Lorrie Moore was an impulse re-read. It has such a wonderfully idiosyncratic form – four short stories followed by a novella, all featuring the same three characters in different versions and permutations: anagrams of themselves, in other words. Here’s what I said when I read it for the first time on holiday, back in 2013. “These people are us! They are us squared!” is clearly me trying to channel Moore. But it’s true that Moore does use humour to set up devastation. And in fact I’d forgotten quite how bleak the end of Anagrams is.

Continue readingFebruary Reading 2021: Bennett, Rainsford, Galloway, Clark, Bonnet, Didion, de Kerangal, Levi

This post is built out of my year-long reading thread on Twitter, but expanded. You can read January’s reading round-up here.

I followed Claire Fuller’s Uncommon Ground with The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett. Two books about twins, which I read – in part – for a thing about twins in literature that I hope to be able to share soon. I was impressed by Bennett’s book without particularly being captivated by it. The characters were strong, and the through-line from generation to generation allowed her to cover a lot of ground. (The plot: twin light-skinned African-American girls in the Deep South of the 1960s go their separate ways, one passing as white, one staying black, their stories reconverging when their daughters meet, these two cousins having been entirely unaware of each other’s existence until they met.)

The narrative is shared out, and I liked seeing the daughters’ lives given as much space as their mothers’, but somehow I felt the novel didn’t have a true centre of gravity, a moral place from which it was being told. Which means the novel’s climactic moment (no spoilers) didn’t really have the emotional punch I was expecting, and wanted This is one of those books that feels rather as if it’s a treatment for a television series. The characters are there, but the work needed to make them really count is not; it’s as if it’s been delegated to a hypothetical director and cast. (Book not pictured as it was a loan, now returned.)

Another twins book was Redder Days by Sue Rainsford, like Bennett an author I hadn’t read before. This was a weird, slippery novel that comes on like an eco-dystopian fiction (shades of Oryx and Crake by Margaret Atwood), dropping us into an ailing world that’s reeling from the impact of some kind of viral cataclysm, and is now waiting feverishly for the oncoming end, a true apocalypse the characters call ‘The Storm’.

But with its isolated setting and tight character list – centred around a pair of adult twins, their mother, and a guru who has drawn them out to a remote commune to await total destruction – it’s more local in its emotional dynamics than global.

This has a stronger narrative drive, with scenes following the twins Adam and Anna scraping by in their gradually unravelling survivalist commune interspersed with journal entries written by their guru, Koan, about the onset of the virus, of which he alone saw the danger from the first moment.

The exact nature of the virus is left unclear, both in its origin and its effects. It seems to turn people into violent zombie-like automatons, but also to turn on themselves, licking at their skin where the red shows through like a cat, until they lick the skin right off. This is all described in a way I’d call poetically evasive, and often compellingly so, but at times I did wish for a bit more clarity. More to the point, why do the characters always have to talk like this too? Living the life they do, I’d have thought Anna and Adam might have been a bit less gnomic in their conversation. At times the writing reminded me of Don DeLillo, king of gnomic evocativeness, but I did want a bit more groundedness.

I read The Trick is to Keep Breathing by Janice Galloway too quickly, so as to be able to discuss it with a PhD student: looking for the angles, the quick and easy lessons. It’s not a novel that reads smoothly. Why should it be? It’s a novel about what was probably at the time called a nervous breakdown, as Joy, a single woman only barely getting by as a drama teacher and working weekends in a bookies battles anorexia and alcoholism on a remote Scottish council estate. The book is as fragmentary as her mind, with some really effective typographical play, including some of the most imaginative use of margins (and restrained at that: it wouldn’t work if there was more of it) I can remember seeing.

Continue readingJanuary Reading 2021: DeLillo, Moore, Townsend Warner, Power, Oyeyemi, Rooney, Fuller

This post is built out of my year-long reading thread on Twitter, but expanded.

I started the year with a short Don DeLillo blitz, research for an academic chapter I’m writing. Some of this was rereading, but Americana, his 1971 debut, was one I hadn’t read before. It is strangely split into different parts, as if moving through different tonal landscapes, which is not an approach I associate with this writer.

The opening is a zippy corporate media satire – at times like Joseph Heller’s Something Happened, published three years later – with lots of cynical male advertising executives trying to screw each other over, and screw each other’s secretaries. It then diverts into a long dull suburban childhood flashback, and then goes on a Pynchonesque road trip across the country, fantasmagorical in parts, skippably dull in others.

My conclusion on Twitter was: In the end I suppose I’m just not in the market for these old myths – which, now that I think about it, is basically a paraphrase of the opening line of Apollinaire’s Zone: “À la fin tu es las de ce monde ancien.” Unlike for Pynchon’s freewheeling carnival of invention, I got the feeling I was supposed to care for these characters, in their struggle to care about themselves, and there were simply too many unexamined assumptions that don’t align with my own for that to apply. It tries too hard to be cool, to shock, to provoke; it flails around to distract you from the fact it doesn’t know what it wants to mean, but as a debut novel it’s still hugely impressive and quite powerful.

I also zoomed through Great Jones Street (1973) and Running Dog (1978). In all these books DeLillo seems to be pushing against the novel form, wanting to find some other way of getting through than via a standard plot arc. Great Jones Street is interesting because of what it says about celebrity, and about music – which is a subject DeLillo has never really returned to. Running Dog to an extent is interesting about the mystique that arises when art and money converge, but he mishandles the thriller plot he starts off by gleefully satirising. The ultra-hardboiled dialogue boils dry, with pages and pages of interchangeable spooks tough-talking each other in the backs of limousines. There is an impressively destructive ending – as destructive as Great Jones Street, but really you get the sense that he’s given up before we even get there. By ‘given up’, I mean given up trying to find a way to resolve the plot in a way that honours equally his characters, his themes, and any remaining sense of reality/realism/credibility.

More on novel endings later in this post.

After DeLillo I moved onto A Gate at the Stairs by Lorrie Moore, which I’ve tried to read at least once before, but didn’t get far into. As with Moore’s best stories it made me absolutely snort with laughter on a regular basis. It also ends wonderfully and movingly and, in a way, thrillingly – doing that thing that I think DeLillo has tried to do, to move outside or above the confines or sphere of novelistic plot: not just giving you what you think deserve from what has come before.

It’s clever in the way it stretches what could have been a fine long short story to over 300pp, but there’s too much stodge: more childhood flashback than is necessary (with Americana, is this a lesson?), even bearing in mind the emotional ballast it contributes to the payoff at the end, and too much compulsive-idiosyncratic detail, delivered by the bucketload. This last is of course a familiar aspect of Moore’s short stories, and perhaps she simply though that the same intensity of narratorial gaze can be endlessly extended without consequence, but it ain’t so.

Lorrie Moore’s short stories work because we can only bear to spend so much time with her characters.

To which her characters would doubtless say, Imagine what it’s like being us!

To which I’d say, That’s not how this works.

Continue readingApril Reading 2020 Part 2: More Proust

Part One of my April 2020 Reading blog post covered the essays of Lydia Davis and Natalia Ginzburg. Read it here.

Apart from Ana María Matute’s The Island (reviewed here) the only other book I finished in its entirety in April was, I think, Sodom and Gomorrah, the fourth volume of Proust. I started reading Proust last year, as my 2019 New Year’s Resolution, but stalled after finishing the third volume on my summer holiday. By October I’d abandoned the fourth volume. (I’ve been dating the passage where I leave off each day, as well as posting notes on another Twitter account, @ProustDiary.) I picked the fourth volume back up in March of this year, and finished it in April. I am now most of the way through the fifth volume, The Prisoner.

So: I am making good progress, but in fact lockdown hasn’t given me that much more time to read than normal. It’s not just that I am working, from home, but that reading, in a busy house of five people (two adults and three teenage boys) can sometimes be a hard activity to justify. Sitting with a laptop is work. Sitting in front of the television is generally a communal activity, and one that can bring the family together outside of mealtimes in a way that board games and jigsaws, because of particular personality types, can’t always do. Reading, apart from at bedtime, is likely to get you looked at strangely – more strangely, I’m afraid to say, than looking at your phone.

I have been enjoying Proust very much in parts, and drifting through others. Indeed, I felt particularly skewered by this aside in Nabokov’s Lectures on Literature:

To a superficial reader of Proust’s work – rather a contradiction in terms, since a superficial reader will get so bored, so engulfed in his own yawns, that he will never finish the book – to an inexperienced reader, let us say…

So let’s call me an inexperienced reader. Certainly, there have been plenty of bits where I have been bored, and irritated. Irritated by the fascination with the workings of society, and bored by the endless unfoldings, like a piece of eternal fractal origami, of the intricate inner imbrications of sometimes mundane psychological impulses. More on this later. Continue reading

April Reading 2020 Part 1: Lydia Davis and Natalia Ginzburg – two essayists

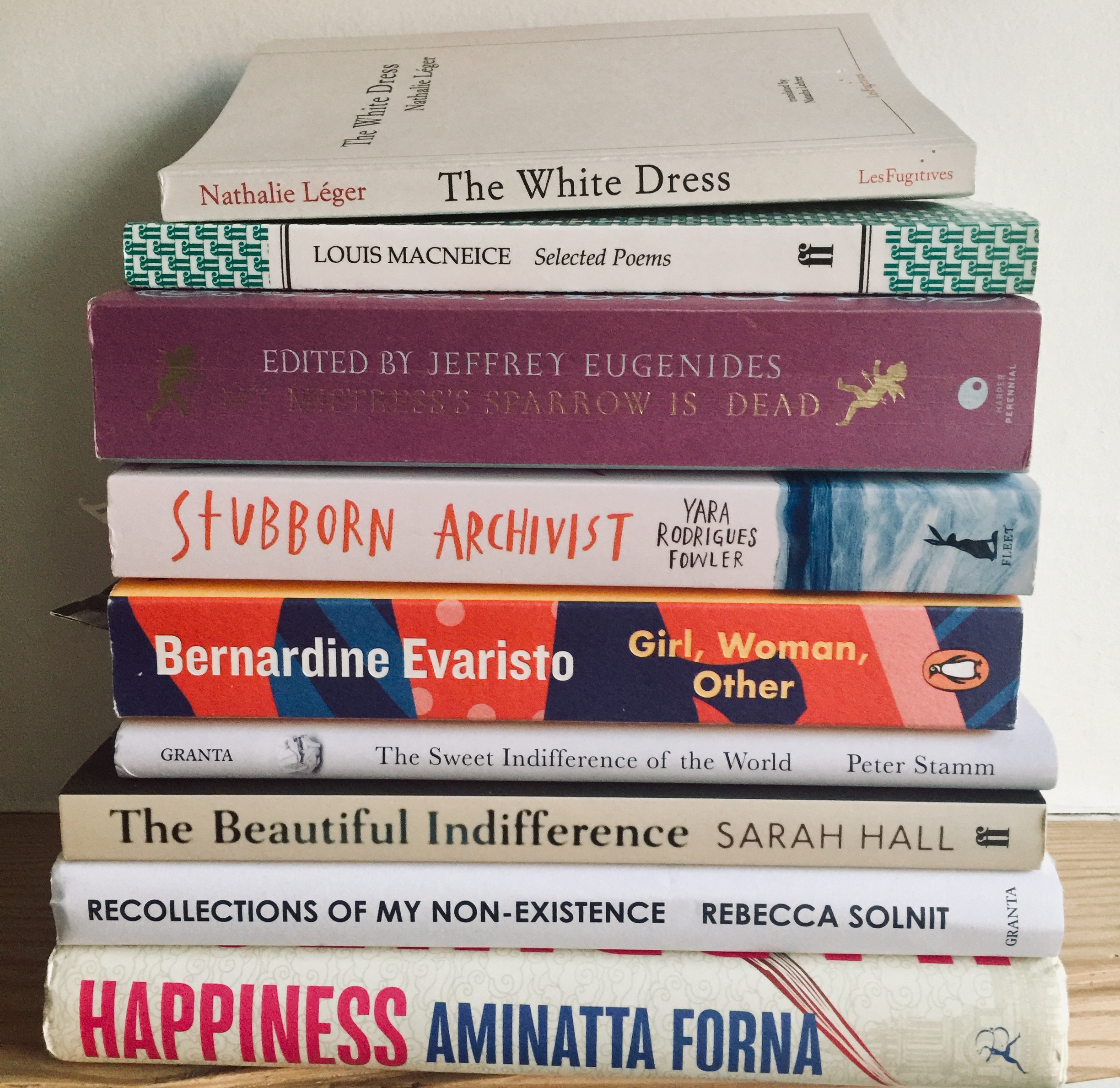

That pile of books looks more impressive than it should. I didn’t read all of the books there cover to cover. The two MacNeice books arrived only at the end of the month, and so far I’ve only read them scavenger-wise, mining them for the parts about the writing of ‘Autumn Journal’, MacNeice’s book-length poem that I’ve been using as a model for a poem I’m writing on our current Covid-times, called ‘Spring Journal’, that you can read here. I also wrote about Ana María Matute’s excellent novel, The Island, here.

That pile of books looks more impressive than it should. I didn’t read all of the books there cover to cover. The two MacNeice books arrived only at the end of the month, and so far I’ve only read them scavenger-wise, mining them for the parts about the writing of ‘Autumn Journal’, MacNeice’s book-length poem that I’ve been using as a model for a poem I’m writing on our current Covid-times, called ‘Spring Journal’, that you can read here. I also wrote about Ana María Matute’s excellent novel, The Island, here.

The essays (Lydia Davis and Natalia Ginzburg) I’ve been dipping in and out of, as you should with essays. Reading the Davis is perhaps the odder experience. She is so marked by her style, so wedded to it, you might say, and that style across all her writing is so essaystic anyway, or bellelettristic – and on occasion faux-essayistic, faux-bellelettristic – that the essays themselves seem to almost dissolve in their own solution.

Her stories often read like boiled-down or reduced essays, like you reduce a sauce – but reduced to the level of density and taste that Heston Blumenthal would approve of – but they also often seem to be poking fun at the idea of essays, of the gap between their confidence of delivery and the meaning of what is delivered.

None of the essays in the book are as outright enjoyable as the best of her stories, and the very placidity of her voice – placidly arch, you might say – means I kind of drifted through them. Some of them I must have read three or four times now, without them becoming fixed in my mind, good though they are.

(The essay about fragments, for example: how perfect, how useful, how now, how me: I love fragments! And she is interesting and useful about fragments, and she carefully considers various people who write in fragments, or forms that are akin to fragments, but at the end of it I’m no wiser than I was at the beginning.)

Perhaps she is trying hard not to be showy in her writing, which is good, in a way, but in another way it is not good. Certainly she is never aphoristic. She is only aphoristic in her stories, where she is lampooning aphoristic writing, with its idea that you can boil down wisdom into apercus:

‘Examples of Remember’

Remember that thou art but dust.

I shall try to bear it in mind.

Natalia Ginzburg is, on the face of it, a very different kind of essayist. (For those that don’t know, she was a prolific Italian writer and political activist who lived through the second world war, though her husband was murdered by the government, and lived to the early 90s.) She is not primarily writing about literature, and so about things thought, but about life, and lived experience.

(Davis seems to give the sense in her writing that she has not experienced anything in her life that has not been thoroughly, even entirely mediated by words. If you walked up to her and tweaked her nose, she would be thinking about the word ‘tweak’ before the sense-impression of the physical act had even reached her brain.)

The Little Virtues (published by Daunt Books) is another book that I have picked up more than once, and read bits of, and probably reread some bits of multiple times. Perhaps it took reading it under lockdown to really make it stick. Ginzburg is a simple writer, rather in the way that Davis is a simple writer, but the difference is that I am reading Ginzburg in translation, whereas Davis always reads like I am reading her in translation. Continue reading

March Reading 2020: Stamm, Hall, Solnit, Léger, MacNeice

I have this problem with the novels of Peter Stamm. I love reading them, but they evaporate from my reading brain after I have read them – like the conceptual artist mentioned in Nathalie Léger’s The White Dress who pushed a block of ice around Mexico City until it melted entirely away. All that is left from my reading of All Days Are Night is a sense of a couple coming together in a ski resort, and an all-night rave of some kind, and of the relationship not working; Seven Years I remember barely at all; To the Back of Beyond is more memorable, perhaps because more high-concept: it is a novel built on an audacious idea that all the same builds that idea into something subtle, and moving.

The only thing I could remember about Stamm’s latest novel, The Sweet Indifference of the World, when I put it in that stack of books read in March, and photographed it with my phone, was the idea of the doppelgänger – which is also foundational to To the Back of Beyond. Beyond that, I could remember not a thing.

Writing this, though, the book has come back to me. It is just as audacious as To the Back of Beyond, and for that reason cannot be described. Let me repeat that Stamm tends to write books that start from an audacious conceit, but which drift away from it, or sink down into it, or in any case hedge or fudge their treatment of that conceit, so that you are never forced to actually judge it in the clear light of day, as you would with a piece of speculative or fantastical fiction that leads you to ask: yes, well, but would it actually work like that?

There is a kind of disintegration loops approach to the writing here – these are thought experiments that are allowed to unfold only so far until they start to disintegrate, while continuing to unfold.

Or: they are Schrodinger’s Boxes novels, that allow their conceits to both be and not be, and honour both in the telling, on the page, where normally things just are.

I’ve just picked the book up and flicked through it: no notes, no underlinings, which is unusual for me. And as I flicked through the book I thought about the nasty trick it plays with its gimmick; and that that’s precisely the reason for having it. It’s a book that undermines its own narrative strategy, or at least its narrator, that kills him off and leaves him alive to see it. It made me think of Simon Kinch’s excellent Two Sketches of Disjointed Happiness, which plays a more similar trick, I think, to To the Back of Beyond. There is something to be written about doppelgängers in fiction – not the simplistic Jekyll and Hyde type, but the type of novel that plays with the foundational idea of narrative that the narrator is a stable, indivisible unit. There’s also Geoff Dyer’s The Search. It is only men who write this kind of novel?

A thought experiment novel, I like that. Perhaps also a little like a Borgesian novel, if Borges hadn’t been too lazy (to use his word) to write one, and had had the patience to let his conceit roll out and gradually disintegrate, like the 1:1 scale map in That Empire in ‘On Exactitude in Science’.

Just for reasons of titular symmetry I’ll move from Stamm to Sarah Hall’s The Beautiful Indifference. Now, I’ve never quite managed to get to grips with Hall as a writer: I’ve failed to make significant headway with any of the novels of hers I’ve tried, and although I remember being quite affected by the story ‘She Murdered Mortal He’ – the part with the creature following the woman along a beach in some far off holiday country – and I’m sure that I did get to the end of the story at least once, I was still surprised by that ending when I read it this time.

This time I read it because Hall was again picked as part of a Personal Anthology. Continue reading

January and February Reading, 2020: Simenon, Chandler, Evans, Markson

January was largely taken up with Simenon – for a piece still forthcoming, for which I tried to read as much of the famously prolific novelist as possible. This was not an entirely rewarding experience. After all, which writer can you honestly binge-read to the extent of weeks and weeks of nothing but them? Bear in mind that your average Inspector Maigret novel is around 170pp long, and you can absolutely blaze through them, so unencumbered are they by much in the way of plot, description or linguistic complexity.

The fact that they are crime novels, that they mostly open with a murder, and are peopled by rough, tough types, don’t stop them being, essentially, soft reads. They are close to Barthes’ Degree Zero Writing. As books, they practically read themselves. This is a good thing, individually: the Maigrets are ideal comfort reads; you can pick them up in confidence that you know what you’re getting. In conjunction, in succession, this is not the case.

Simenon’s romans durs (straight or hard novels) are different. Without the broad, brooding humanity of Maigret – so long as you’re not Jewish, or eastern European, or female and ugly – they give off an acid, acrid stench. Their anti-heroes are nastier than Patricia Highsmith’s basically amoral villains.

So, reading lots of Maigrets back to back was not a particularly edifying experience – in my photo they’re represented by Maigret in Vichy: a fine example. It doesn’t help that Simenon seems to have got more slipshod in the later novels. Nowhere really do the books offer up an ‘extended universe’, beyond the dependable lode stars of Madame Maigret and the inspector’s closest colleagues at the Quai d’Orfèvres, but they do repeat themselves, and they get sloppy. I will go on reading them, and acquiring them in their lovely new Penguin editions, and I will seek out more of the non-Maigrets, but by the time I filed my piece I was desperate for something sparkier, something punchier, something with more heart and mind. I turned to Raymond Chandler, thinking I could make do with one story from Pearls a Nuisance, but actually reading all three of them: the title story, ‘Finger Man’, and ‘The King in Yellow’.

Oh, Chandler is such a joy. Like Simenon he knew well enough to make his hero(s) good, honest men with gruff exteriors, knights in tarnished armour. Like Simenon, he knew that we don’t want Poirot or Holmes-style clever-clever cryptic crossword mysteries; we’re quite happy to tag along behind the detective, picking up clues with them. Bad guys are usually pretty obvious, after all. Most murder is decidedly uncryptic. Unlike Simenon, however, Chandler is a delicious prose stylist, who would never settle for Degree Zero. (He is so even in ‘Pearls are a Nuisance’, in which the first-person private dick protagonist talks like a Dulwich College stuffed-shirt, rather than a laconic, tooth-pick chewing gumshoe; when called on it, he answers:

‘I cannot seem to change my speech, Henry. My father and mother were both severe puritans in the New England tradition, and the vernacular has never come naturally to my lips, even while I was in college.’)

But it’s not just the case of a way with a particular vocabulary. The is a splendid sharpness to the narration in terms of what is told, and what is not. Here is a paragraph from ‘Finger Man’, in which the hero, another standard-issue private eye, comes back to his office to find a client, a standard-issue femme fatale, in his waiting room.

I unlocked the other door and she went in and sat in the chair where Lou had sat the afternoon before. I opened some windows, locked the outer door of the reception room, and struck a match for the unlighted cigarette she held in her ungloved and ringless left hand

The ‘ringless’ is a good detail, but you’d expect that from a private eye. It’s the fact of how that unlit cigarette comes right at the end of the paragraph, like the verb in a German sentence, and the way it sits there, patiently, on the page, shows us that she’s been sitting there like that for a while – for the time it takes him to lock the door and open the windows – waiting for him to light it, in the way of femmes fatales down the ages. And it only takes a second look at that sentence to realise (or guess, if you’re being picky) that he, the private eye, had spotted the cigarette, there in her hand, just as he spotted the ring, at some point in his tour of the office windows, and left her there, waiting, while the rest of the sentence rolled itself out. It’s not narrated, but it’s there. Continue reading

September and October reading: Atkinson, Hesse, Popkey, Sōseki, and a lot of other bits and pieces, honest

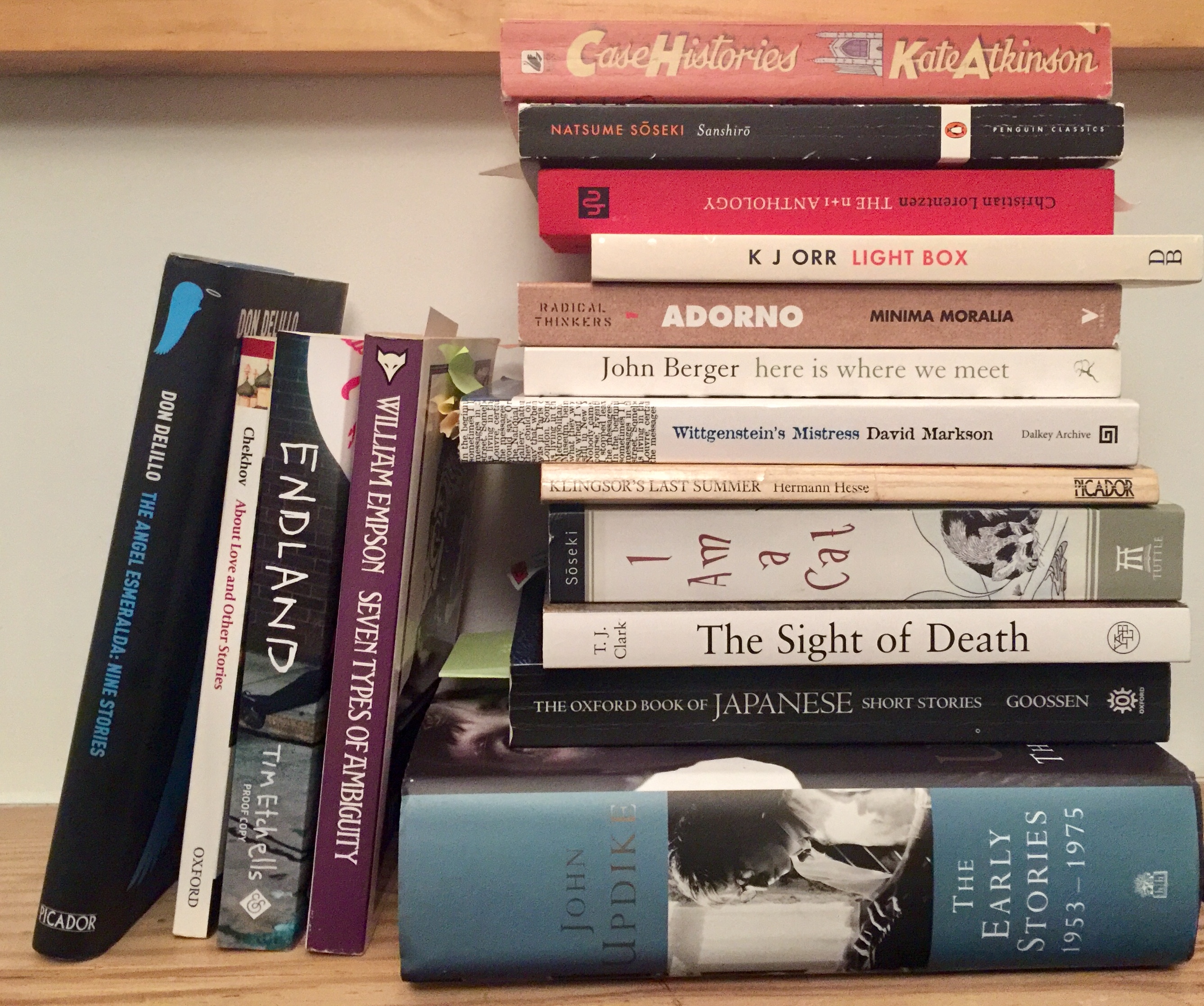

Wow! Look at that pile books! Did you read them all?

No, of course not. Don’t be so stupid.

Reading has been tricky over the last couple of months – I managed to completely miss out on my ‘September reading’, beyond taking a photo of the relevant book pile. The truth is, I didn’t read all of ANY of the books stacked up under September with the exception of Klingsor’s Last Summer, by Hermann Hesse, which is really just three stories slung together. (Bonkers in part. Boringly chauvinistic in the main.) The only other books I’ve read in toto since the beginning of September, when I raced through Running Dog by Don DeLillo are:

- Case Histories, by Kate Atkinson

- Topics of Conversation, by Miranda Popkey

- Sanshirō, by Natsume Sōseki

But, as I’ve written before, much of my reading is piecemeal. I mean, look at all those other books I picked up, read a bit of, and put back.

Why is this? Perhaps it is to do with the attention deficit that is supposedly affecting us all. Perhaps it is to do with my job, in which I have to read lots of students’ work. Perhaps it is to do with my online project A Personal Anthology, in which every week I ask someone to pick and introduce a dozen favourite short stories… I mean, it’s not like I read all twelve, every week, but I always read at least a few of them, both those I don’t know and those I do. (For instance, oh man, ‘Gusev’ by Anton Chekhov, as picked by Darragh McCausland!) Perhaps it’s the fact that I happen to be judging the Manchester Fiction Prize this year, alongside Nicholas Royle, Lara Williams and Sakinah Hofler, which means much of my spare time is spent reading entries. And perhaps it’s to do with the fact that this year I set myself the project of reading all of Proust, for the first time. (I’m not going to make it, by the way. But hey-ho, it was always just a project.)

But there is more to it than that.

I write. I review (less, just now). I teach. Much of my life is taken up with books and literature and writing, and for that I’m profoundly grateful. But the constant irruption into my eyes of real, good, meant words from all sides – a river of words bursting into an overwhelmed house through every opening – means that whole books have to fight to stake their claim.

To put it another way, the idea of a novel – which is, to be blunt, my foundational idea of what words, put together, can achieve – has started to seem crucial, less joyous.

The novel is the type of book above all which insists on being taken as a whole. It is a monad, as Leibniz would have had it; an absolute unit, if you know your memes. It ring-fences its words, encases them in a protective membrane, so as to stop you from taking any of them except on its own terms. A story or poetry collection is built to be divisible. A non-fiction book, even a piece of narrative nonfiction, can be thought of as containing information in discrete units, separable and parsable without the whole.

The novel is the thing that says: I only make sense if you read all of me. It’s all of me, or nothing! No cherry-picking allowed.

A novel is best read, in my experience, either slowly and steadily, over a week or two, in sedate and regular portions, so that your imagination comes to a reasonable accommodation both with the narrative pacing and with the demands of everyday life, negotiating between the two of them, making space for one in the other, and for the other in the one – or it is best read at a gallop, picked up at every opportunity, a page snatched here or there, between bites of breakfast, between meetings, between conversations: this novel consuming your every waking thought.

Over the last couple of months, I’ve been able to do the latter – twice, with Topics of Conversation and Case Histories – but not the former, or not successfully. Sanshirō is the kind of book that would work perfectly as a leisurely fortnight’s read: not much happens; the chapters are short; the characters are agreeable. (It might help to know that the book was originally serialised in weekly instalments.) You could read a decent chunk of it on a good-length train journey.

(It is the third novel by Sōseki that I’ve read, and certainly it doesn’t reach the poetical highs of Kusamakura or the tragic depths of Kokoro. It is a calmative, a thoroughly delightful and spring-like story about a young man come from the country to Tokyo to study at the university, but although I enjoyed it, it didn’t fit the slightly frantic rhythm of this particular autumn.)

What does a novel have to do, then, to grab you by the collar and force you to read it? To elbow its way into your life and take up temporary residence? Well, an itchily cryptic plot is one way to do it. Case Histories is the first book I’ve read by Kate Atkinson, though I own maybe four or five of them. I keep picking them up, trying the first page or two, then putting them back. (Probably best skip the next paragraph if you’ve not read it, and get to Matilda Popkey, as there will be plot-spoilers.)

Case Histories is Atkinson’s first novel featuring a now-recurring private eye, Jackson Brodie, and from reading it you’d think that she didn’t particularly intend to ever bring him back: the end of the book seems to gift him with the kind of narrative closure most series-writers would only dream of when they’re 95% sure they want to retire their egg-laying goose. (When they’re 100% sure, of course, they close them down completely.) The book is also at odds with the crime genre itself in terms of narrative structure. It opens with the matter-of-fact description of three unconnected family tragedies taking place over x years – one disappearance, and two murders. It’s a bravura performance, with none of the shivery glee with which the worst kind of crime thrillers serve up dead or gone girls and husband-topping psycho-bitches. But much of the rest of the book’s plotting is devious in the extreme, basically challenging the reader to work out not just the mystery of who did the crimes, but the secondary mystery of how these disparate narratives are going to come together, other than that Brodie is investigating them all. They do, in simple and more tangential ways, but it’s a bit of a slight of hand. You couldn’t write more than one mystery book this way.

That reaction only comes right at the end, however. On the way there you are treated to a wonderful mixture of the plottish and the character-led. The book is character-driven, you might say, but by characters who can’t drive very well. It reminded me of Iris Murdoch, for its plainly, even humdrumly unusual characters – but an Iris Murdoch who either can’t write well, or doesn’t care for good writing. I mean, Atkinson is a whizz at plotting, at characterisation, and there is some splendid dialogue here – I laughed, I turned the pages, zip-zip-zip – but at no point in the book did a sentence slow me down, or make me catch my breath, or suggest I reread it or underline it or tweet. Reading the book was like eating a huge bowl of plain pasta, cooked exactly as you like it, but with no sauce. It seemed almost willed. She’s clearly too good a writer not to know what she’s doing. Now I need to read some of her other books to see if she makes anything else of it.

Miranda Popkey’s Topics of Conversation I won’t go into here in detail, because I hope to be able to review it. It’s an excellent debut that splashes around in the currently warm waters of autofiction. You might say it’s a touch derivative – and in fact it has an incredible two-page acknowledgements section at the back that lists all the books, films, essays, plays and pasta recipes that inspired it, however tangentially. It’s wonderfully in your face. To be glib, it’s Rachel Cusk by way of Sally Rooney. But it deserves something more than glibness. I want to read it again, slower. I’m tired. Some more books just arrived. I’m off to not read them all, from cover to cover.

Many thanks to Serpent’s Tail for the Popkey, which is out in February 2020.