Category: Reading

Occasional review: on finishing A.S. Byatt’s ‘Frederica quartet’: The Virgin in the Garden, Still Life, Babel Tower, A Whispering Woman

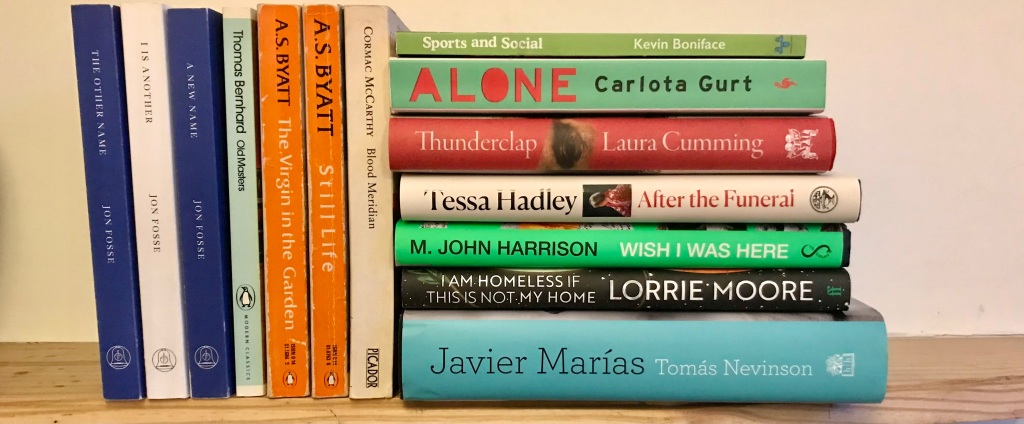

A. S. Byatt died on 16 November 2023 and the next day, when her death was announced, I took down The Virgin in the Garden from the shelf, where it had sat unread for I don’t know how long, and began to read it. I’d previously only read Possession by her, plus some short stories, which I’d liked well enough, but this I enjoyed far more. So much so that I went straight from The Virgin in the Garden to the second novel in ‘the Frederica Quartet’, Still Life, as I already had that to hand, but then paused for a couple of months before reading Babel Tower and then had another pause before A Whistling Woman, which I finished at the start of April 2024. I thoroughly enjoyed the whole of the quartet, and found parts of it absolutely thrilling, intellectually and on occasion emotionally. These are novels of ideas, and ambition, but are also threaded through by a writer’s love for her characters: love here meaning care and attention, or attentiveness.

These books get called ‘The Frederica Quartet’ because they follow the life and intellectual development of one central character, Frederica Potter. Frederica is 17 at the start of the first book, which is set in the year of Elizabeth II’s coronation, 1953, and she’s in her mid 30s at the end of the last book, in 1970 – in fact in historical terms she’s an exact contemporary of Byatt. The books do expand their concerns beyond Frederica, sometimes far beyond, and sometimes too far. To start with we spend as much time with her parents, the domineering Bill and emollient Winifred, and her siblings – elder sister Stephanie and younger brother Marcus – and also with Alexander, the older man with whom the teenaged Frederica is infatuated. In later books this diffuseness of focus increases, such that at times Frederica seems almost tangential. This isn’t necessarily a good thing, especially – cough – if you are in love with Frederica, as it’s possible to be in love with, for instance, As You Like It‘s Rosalind. Byatt says in an interview: “It isn’t Frederica’s book – though she’s the sort of person who would muscle in and try to take it!”

These notes draw on and develop the comments in my 2023 and 2024 Reading threads on Bluesky.

My first point, looking back on the quartet, is the oddity that the period covered by the novels is shorter – at 17 years – than the period over which they were published: 24 years. In other words the novels became more historical as the period they covered receded – and the novels in part are realist depictions of a specific period in English social and cultural history, a thrusting and exciting period that saw the rise of television and the new universities, and of the counter-culture of the 1960s.

As a series of books these are less programmatically ‘historical’ or ‘historical-thematic’ than, say, the Rabbit tetralogy, or A Dance to the Music of Time. (As a side note, and based on my distant memory of reading Powell’s twelve-novel sequence, the treatment of the anarchic-religious commune in Byatt’s A Whistling Woman is rather similar to the Harmony cult in Hearing Secret Harmonies.) The treatment of early BBC Two-style television is great – all Jonathan Miller and ‘Alice in Wonderland’ – but the attempts at creating a Bowie-esque pop star fall flat. Byatt can do many things, but she can’t do rock. Occasional historical events are mentioned in passing, but Byatt is more interested in the intellectual and spiritual tenor of the times than their politics, in blunt terms.

Here are the dates of the novels:

- The Virgin in the Garden: published 1978; set 1953.

- Still Life: published 1985; set 1953-1956

- Babel Tower: published 1996; set 1964-1967

- A Whistling Woman: published 2002; set 1968-1970.

Part of the gap between the second and third novel was, Byatt has said, caused by the death of her son, killed aged 11 by a drunk driver. She also delayed writing Babel Tower to write Possession, which apparently seemed like it would be more fun to write. It was – and it was also a massive commercial success, winning her the Booker Prize in 1990. Which doubtless also delayed things.

The books are hugely ambitious. They want to give a picture of England in London and Yorkshire over this period of accelerated upheaval, but they also offer the pleasures of a family saga (how does parenting affect children? how do siblings get along? who will Frederica sleep with, and why?), and they are full to brimming of the ideas that the characters are having: about science, art, sex, psychology, religion, education, literature. The ideas are built into arguments, in conversations and letters, but also in the characters’ thoughts, thanks to Byatt’s brilliant use of omniscient narration. That said, I agree with Ruth Bernard Yeazell’s balanced LRB review of A Whispering Woman, in which she says:

“it’s possible to feel that the Potter novels occasionally suffer from an overindulgence of their author’s cognitive appetites. In a recent interview, Byatt credited Proust with having taught her that one could ‘put everything into’ a novel, but A la recherche du temps perdu may not be the safest model in this respect; and of course much depends on how ‘everything’ is reimagined and articulated. The problem is not that Babel Tower or A Whistling Woman ‘smells of the lamp’, as Henry James famously complained of Eliot’s historical scholarship in Romola, but that the proliferation of vocabularies and allusions – not to mention the sheer number of characters, many of them introduced in previous volumes – sometimes threatens to bury the narrative rather than illuminate it.”

By the way, do NOT so much as glance at any more of Yeazell’s review before reading the books if you want to avoid major spoilers!

Although Byatt said she was responding to D. H. Lawrence and George Eliot in writing the books, my original response to The Virgin in the Garden was that:

she takes the Murdochian novel – the concatenation of sex and ideas produced by daft, intelligent, passionate people in a closed environment – and i) improves the plotting and ii) gives the prose a touch of the Jamesian-Bowenesque high church style, tightening a corset that Murdoch wears slack.

It’s good to see the omniscient narrator done well, when it’s currently so out of fashion. Byatt makes it work at a domestic level – the smooth passage between different characters’ POVs in the Potters’ kitchen – but she’s also up for orchestrating major set pieces, of which there are many, with aplomb.

Here’s Byatt, in that same interview, talking of George Eliot:

“Sometimes she says, ‘He thought,’ and sometimes she almost suggests that she doesn’t quite know what somebody thought, but that it was a bit like this. She can do all those things, because she’s got a flexible instrument.”

She also does the interesting thing of starting (after the prologue) with a central character (Alexander) who is not there at the end. His emotional arc drives the plot of the first book, but is not absolutely central to the thematic concerns of the novel. And in fact the intricate plotting of a love affair or mutual seduction involving this 34-year-old male teacher and Frederica’s wilful, self-possessed 17-year-old schoolgirl (he’s not her teacher, if that makes it any less reprehensible) is very carefully negotiated – were things different then? you wonder, in anguish – and it pays off in a way I could only applaud with my hands over my eyes, as it were.

Although the plotting of the first book is tight, this loosens as the quartet goes on. In part this is to let all the ideas in, and all the characters – the long cast list is important for the novel’s realism, so that Byatt can move up and down the country and through British society without making the world of the book too compressed and coincidence-prone. Because of this some of the secondary characters become rather easy to muddle up – or easy, in fact, to give up on identifying at all. Sometimes re-encountering, say, a Monica Thone, or Geoffrey Parry or Thomas Poole late in one of the novels is a bit like seeing someone coming towards you across the room at a party, when you think, I know you, I know I know you, but who the hell are you again?

Byatt is also generous and catholic in her use of different literary modes (or ‘instruments’, to her use term). The third and fourth books include extended passages from two different novels-within-novels, and the fourth book has long epistolary sections, with Babel Tower also including legal transcripts and four very funny ‘reader reports’ that Frederica writes on books from a small publisher’s slush pile. When Frederica gets divorced we don’t just get the legal letters; we also get Frederica’s angry Burroughs-style cut-ups of those same legal letters. Her legal deposition for the divorce is seen first as her anguished scribbled notes and then in impersonal legalese.

These postmodern techniques are mostly there for a reason, and they build and echo the novels’ themes in a variety of ways. Byatt gives a spoken cameo to Anthony Burgess (no longer alive at time of publication) and mentions in her acknowledgements ‘borrowing’ an Iris Murdoch character – who, I wonder. I was less taken with the increasingly silly character names. You can roll your eyes at an ambitious academic called Gerard Wijnnobel – ha and indeed ha – but the likes of Hodder Pinsky, Elvet Gander, Kieran Quarrell and Avram Snitkin – all from A Whispering Woman – pile up with no real sense of who they actually might be, let alone why they’re called that.

Byatt also chops and changes her structural approach to the books.

- The Virgin in the Garden has 44 named and numbered chapters across three sections, plus a proleptic (flash-forward) prologue to 1968.

- Still Life likewise has 33 named and numbered chapters, though not split into sections, and a proleptic prologue that actually hopfrogs the entirety of the quartet’s chronology to land us in 1980!

- The last two books are simpler, which is perhaps a shame. Babel Tower has 21 numbered but un-named chapters, and no sections, and a one-page prologue that is more epigraph than scene.

- A Whistling Woman has 27 chapters, again unnumbered, again not in sections and this time with no prologue at all.

The sense I hope this gives is that Byatt is not programmatic about her books. They change their approach in line with her developing skills and intentions as a novelist. At times it seems like she’s improvising, as a concert pianist might improvise – or she’s like Glenn Gould or Keith Jarrett, humming along with her keyboard work.

An example here from the romance between Alexander and schoolgirl Frederica in The Virgin in the Garden, when Frederica says to him: “Just hold me a little. Without obligation.”

Continue readingBooks of the Year 2023

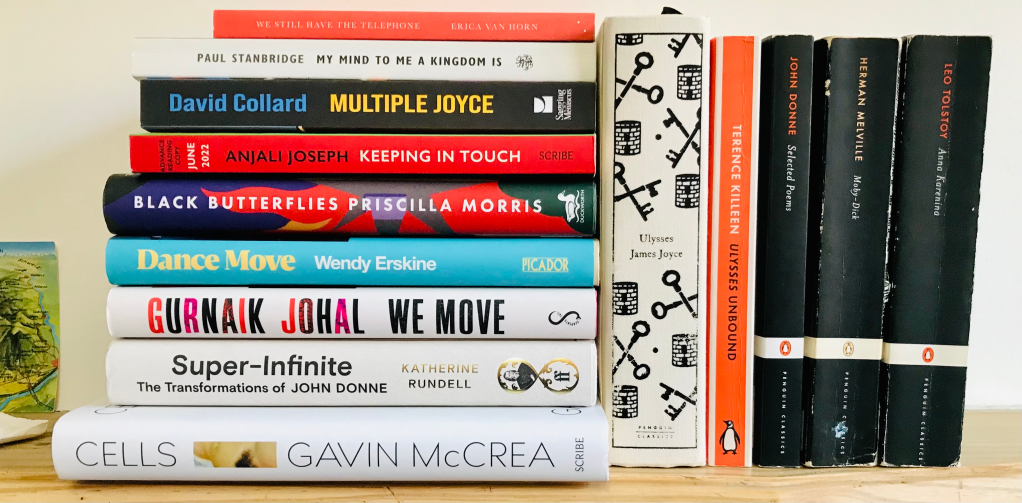

As for the last few years, I’m reading fewer new books, in part as my university teaching replaces book reviewing as the driver of much of my ‘strategic’ reading, and in part perhaps because of my continued and always-belated attempted to catch up with unread classics (2023: War and Peace; 2022: Moby-Dick, Ulysses, Anna Karenina; 2019-20: In Search of Lost Time; Middlemarch; 2024? I’m not sure yet…)

Anyway, here are my ‘books of the year’ – I’m keeping the title for consistency’s sake, though really this is intended as a record of my reading. In 2023, as I’ve done in some of my previous years, I kept a ‘reading thread’, which migrated halfway through the year from Twitter/X to Bluesky. (I’m keeping my X account live, really just for the purposes of promoting A Personal Anthology; I’ve deleted it from my phone, and carry on my book conversations now on Bluesky). I’m grouped the books according to i) new books, i.e. published in 2023 ii) books read by authors who died in 2023 iii) other books, with a full list at the end.

Best new books

After the Funeral by Tessa Hadley was my book of the year. She is truly a contemporary master of the short story. I delight in her rich use of language, in her ability to draw me into characters’ lives and particular perspectives (though I’m aware that, in broad sociological terms, those characters are very much like me) and in the power and deftness with which she manipulates the narrative possibilities of the short story. She’s like an osteopath, who starts off gently – you think you’re getting a massage; you feel good; you feel in good hands – but then she does something more dramatic, leaning in and applying leverage, and you feel something shift, that you didn’t know was there. ‘After the Funeral’ and ‘Funny Little Snake’ are both brilliant stories well deserving of their publication in The New Yorker. ‘Coda’ is something else: it feels more personal (though I’ve got no proof that it is), more like a piece of memoir disguised as fiction, which is not really a mode I associated with Hadley. I read or reread all her previous collections in preparation for a review of this, her fifth, for a review in the TLS, and I have to say: there would be no more pleasurable job that editing her Selected Stories – the collections all have some absolute bangers in them – though equally I’d be fascinated to see which ones she herself would pick.

Tomás Nevinson by Javier Marías, translated by Margaret Jull Costa. Not a top-notch Marías, but a solid one: Nevinson is a classic Marías sort-of-spook charged with tracking down and identifying a woman in a small Spanish town who might be a sleeper terrorist, from three possible targets, which naturally involves getting close to and even sleeping with them. I found some of the prose grating – flabbergastingly so for this writer (“we immediately began snogging and touching each other up” – I mean, come on!) – but the precision of the novel’s ethical architecture is absolutely characteristic.

Alone by Carlota Gurt, translated by Adrian Nathan West. A compelling and moving Catalunyan novel about the stupidity of thinking you can sort your life out by relocating to the country. Similar in theme to another book I read this year (Mattieu Simard’s The Country Will Bring Us No Peace) though I liked that one far less. I won’t say much about it as I read it without preconceptions and recommend it on the same terms. I will say it reminded me of The Detour by Gerbrand Bakker, which is another novel of solitude and the land, which again benefits from stepping into as into an unknown locality.

I am Homeless if This is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore. Oh boy. I love love love Moore at her best and though this aggravated as much as delighted me it’s been nagging me ever since I really want to go back and read again. [NB I have gone back to it, as my first book of 2024, and am being far less aggravated than on the first read). After a brisk, unexpected and exhilarating opening the novel seems to go into stasis, a slow series of disintegrating loops. It fails to do the thing that Moore usually seems to do quite effortlessly: keep you dizzily engaged with a cavalcade of daft gags and darkly sly sharper wit and observation. The protagonist, Finn, seems to miss what Moore usually gives her central characters: a dopey friend to dopily muddle through life with. He has a brother, Max, but he’s dying, and an ex, Lily, who, well… But all of this is done in flat dialogue wrestling with the big questions. Moore usually lets the big questions bubble up from under the tawdry minutiae of life (as, brilliantly, in A Gate at the Stairs); here, they’re front and centre. More tawdry minutiae, I say! I think part of my frustration with the novel comes from a place of ‘Creative Writing pedagogy’. Wouldn’t it be better, I think, to open up Finn’s character, show him as a teacher, his banter with the students, and his entanglement with the head’s wife? Rather than making all of that backstory, dumping it into reflection. The scene with Sigrid, for instance – her attempts to flirt with Finn – would be stronger if we’d already met her in the novel, already seen their relationship (such as it is) in action. You tell students, first you establish the ‘normal’ of the protagonist’s existence, then you throw it into confusion. So, am I giving LOORIE MOORE MA-level feedback? Well, yes. To which the response (beyond: “she’s LORRIE MOORE”) is: she’s not writing that kind of ‘normal’ novel. For every bit of LM brilliance (the gravestone reading “WELL, THAT WAS WEIRD”; the line “Death had improved her French”) there’s something off, that should or could be fixed or cut: the cat basket sliding around on the car backseat; the scene where Finn’s car spins off the road.

A Thread of Violence by Mark O’Connell. A suavely written book that digs into the true crime genre but stops short of the moral reckoning it at least flirts with: that in truth it shouldn’t exist – as a published book, at least. Will surely sit on reading lists of creative non-fiction in the future.

Tremor by Teju Cole. Read quickly and carefully (in physical not mental terms: it was bought as a Christmas present and sneakily read before being wrapped up and given ‘as new’), with the full intention of going back and reading it again. Cole is a literary intelligence for our times, that I’d drop into the Venn diagram of the contested term ‘autofiction’, not for its supposed relationship to the author’s life, but for its relation to the essay form.

Wish I Was Here by M. John Harrison. In fact I haven’t finished reading this. But I dug what I read, and will go back and finish it, but feel like I wasn’t in the right headspace for it at the time. It’s a book to sit with, to scribble on, to squint, to make work on the page. It’s not a book to do anything as basic as just read.

Sports and Social by Kevin Boniface. Stories from the master of quotidian observation that somehow avoids observational whimsy (the curse of stand-up comedy). If we build a new Voyager probe any time soon this should be on it, but failing that I’d recommend putting a copy in a shoebox and burying it in your garden, for future generations to find.

Thunderclap by Laura Cumming. A slight cheat, as I finished this on the first of January 2024. But it was a Christmas present and perfectly suited the slow, thoughtful last week of the ending year. I loved Cumming’s take on Dutch art, and how its thingness is often overlooked, and I loved the way she mixed together scraps of biography of Carel Fabritius (about whom little is known) and a memoir of her father (James Cumming, about whom little is known to me). The fragments hold each other in tension very well, but it’s not fragments for fragments’ sake. Cumming delineates a space for thinking about art, and its relationship to life, and lives, and other elements, big and small: death, sight-loss, colour-blindness, the nature of explosions, dreams, more. Tension’s not the word: it’s more like a provisional cosmology, that puts thematic and informational pieces in orbit around each other. There’s no symphonic tying-together at the end, but things are allowed back in, with new things too.

I only started underlining (in pencil: it’s a beautiful book!) towards the end. Here are some lines:

- “Open a door and the mind immediately seeks the window in the room”

- “Painting’s magnificent availability”

- Of an explosion witnessed first-hand: “a sudden nameless sound […] a strange pale rain”

There is so little known about Fabritius, with so many of his paintings lost, but really there’s so little known about any of us, the book suggests… and most of our paintings will be lost (as paintings by Cumming’s father have already been lost) but yet looking at art brings a special kind of knowledge, showing us “the intimate mind” of the artist, as of a novelist, or – as here – a writer. The love of art and of life shines through, or not shines, but diffuses, as in one of the grey Dutch skies Cummings writes about.

“But I have looked at art” she says, and she shares that looking (as does T. J. Clarke in his magnificent The Sight of Death) but she also opens up a space for looking. If “But I have looked at art” is an understatement, a compelling gesture of humility, then Cumming can also write, again towards the very end of the book, “What a glorious thing is humanity” and not have it jar, or smack of pomposity. There is much to cherish – much humanity (and what else is there in the world truly to cherish? – in Thunderclap.

Continue readingBooks of the Year 2022

Reading habits and outcomes change according to personal inclination, of course, but also according to external factors: life circumstances, temperament and age, the demands of a job. All of which is to say I’ve read fewer new books this year than in the past. I review less than I used to, certainly, and when I read for work (teaching Creative Writing at City, University of London) I’m more interested in the books that came out a year or two ago, and that have perhaps started to settle into continued relevance, than the whizz-bang must-read of the year.

Of the new books I have read, that have made a lasting impression, here are seven:

Ghost Signs by Stu Hennigan (Bluemoose) is an unforgettable journal of the 2020 Covid pandemic lockdown, during which the author was furloughed from his job working for Leeds City Council libraries and volunteered to deliver food parcels to vulnerable people and families. The eerie descriptions of empty motorways and fearful faces peering round front doors evoke that weird time in 2020, but the true and lasting impact of the book comes from Hennigan’s realisation that the poverty and distress he discovers in his adopted city isn’t down to the pandemic at all, but to entrenched government policies that have forced council services to the brink, and thousands of people into shamefully desperate circumstances. It’s a political book, sure, but one written out of necessity, rather than out of desire or ideology, and one that you want every politician in the country to read, and quickly, so that the responsibility for dealing with the issues it raises passes to them, rather than resting with Hennigan. (That’s the problem with writing books like this, isn’t it? That by being the person who identifies or expresses the problem, you become inextricably linked to it, a spokesperson, a talking head, with all the emotional labour that implies.)

(Ghost Signs isn’t in the photo because I’ve given away or lent both copies I’ve owned.)

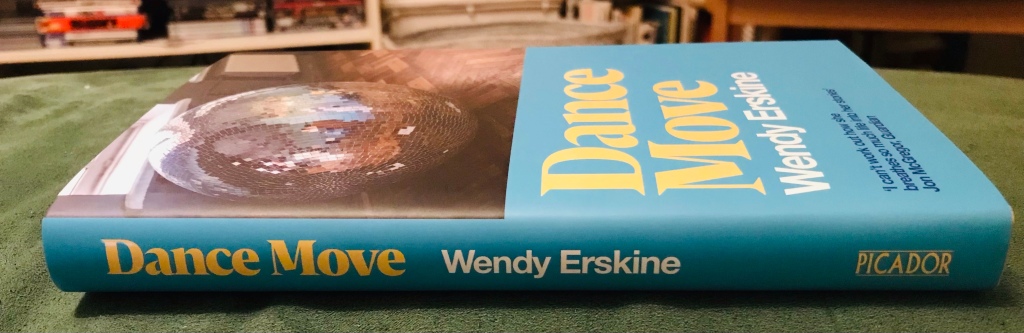

I heard Hennigan read from and talk about the book at The Social in Little Portland Street, London this year, and the same goes for Wendy Erskine, who was promoting her second collection of short stories, Dance Move (Picador). Erskine is one of the most talented short story writers in Britain and Ireland today, and I’ll read pretty much anything she writes. Dance Move is at least as good as her first collection, Sweet Home, and if you made me choose I’d say it’s better. The stories are muscly, chewy. Erskine has had to wrestle with them, you can tell. They are worked. She takes ordinary characters and by introducing some element that might be plot, but isn’t quite, she forces their ordinary lives into unprecedented but gruesomely believable shapes. These stories are perfect examples of the idea that plot and dramatic incident should be at once surprising and inevitable. But the thing I love most about her stories (I wrote a blog post about it here) is how she ends them:

You are so immersed in these characters’ lives that you want to stay with them, but the deftness of the narrative interventions means that the stories aren’t wedded to plot, so can’t end with a traditional narrative climax or denouement.

(As David Collard said, in response to my original tweets, “Wendy Erskine’s stories don’t end, they simply stop” – which is so true. Perhaps it would be even better to say, they don’t finish, they simply stop.)

So how does she end them? She kind of twists up out of them, steps out of them as you might step out of a dress, leaving it rumpled on the floor. In a way that’s the true ‘dance move’: the ability to leave the dance floor, mid-song, and leave the dance still going.

Take the story ‘Golem’, definitely one of my favourites in the collection. It’s a story that does everything Erskine’s stories do. It densely inhabits its characters’ lives, and it has its comic-surreal interior moments, but most incredibly of all, it manages to end at the perfect unexpected moment. The story goes on, but the narrative of it ends. It departs, exits the room, taking us with it.

Perhaps the best way to put it is that you feel that, yes, the characters are ready to live on, and yes, you’d be ready to keep on reading the prose and the dialogue forever, but no, you wouldn’t want the stories themselves to last a single sentence longer.

My other favourite short story collection of the year is We Move by Gurnaik Johal (Serpent’s Tail), which is a thoroughly impressive debut, that again seems to show how short stories can be the perfect receptacle for characters: they give us characters, rather than plot, rather even than writing, or prose, or words. The difference between this and Dance Move is that We Move, to an extent, looks like the traditional debut-collection-as-novelist’s-calling-card. I’d love to read a novel by Johal – or for Erskine, for that matter, but equally I’d love her to just go on writing stories, because the more people like her keep writing stories, rather than novels, the stronger and more vital the contemporary short story as form will be.

My Mind to Me A Kingdom Is by Paul Stanbridge (Galley Beggar – publisher of my debut novel, though I don’t know Paul) is an exquisite piece of writing that does live or die by its sentences. (Narrator: it lives). An account of the aftermath of the author’s brother, it is indebted to WG Sebald, in terms of the way it leans on and deals out its gleanings of learning, but also in terms of how its lugubriousness slides at times into a form of humour, or perhaps of playfulness. No mean feat when you’re writing about a sibling who killed himself. A hypnotising read.

My most unexpectedly favourite book of the year was Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne, by Katherine Rundell (Faber), which I wrote about for The Lonely Crowd, here. I didn’t know I needed a biography of a Sixteenth Century English Metaphysical poet in my life, but Rundell fairly grabs your lapels and insists you read him. Frankly I’d read any book that contains lines like “A hat big enough to sail a cat in” and “joy so violent it kicks the metal out of your knees, and sorrow large enough to eat you” in it.

My final new book of the year is We Still Have the Telephone by Erica van Horn (Les Fugitives), which I received as a part of a support-the-publisher subscription. It’s a delightfully sly and spare account of the author’s relationship with her mother. “My mother and I have been writing her obituary” etc. One to file alongside Nicholas Royle’s Mother: A Memoir, and Nathalie Léger’s trilogy of Exposition, Suite for Barbara Loden and The White Dress (also from Les Fugitives) as great recent books about mother-child relationships.

A mention here too for Reverse Engineering (Scratch Books) which is a great idea: a selection of recent short stories accompanied by short craft interviews with their authors. It’s got succeed on two levels: the stories themselves have to be worth reading, and the interviews have got to add something more. It succeeds on both, with wonderful stories from some of our best contemporary story writers: Sarah Hall (at her best the best contemporary British short story writer), Irenosen Okojie, Jon McGregor, Chris Power, Jessie Greengrass etc, and useful commentary. I look forward to reading more in the series.

(Copy not shown in photo as loaned out.)

I’ll include another section here on new books, but new books written by writer friends or colleagues: Cells by Gavin McCrea (Scribe) is a jaw-droppingly raw and honest memoir that bristles with insight, and revelation, and liquid prose. Keeping in Touch (also Scribe) is my favourite yet of Anjali Joseph’s novels, a properly grown-up rom-sometimes-com, that makes you want to get on airplanes, travel the world, travel your own country, wherever that is, talk to people, work people out, and fall in love, which is perhaps the same thing. And Black Butterflies by Priscilla Morris (Duckworth) is a novel I’ve been waiting more than a decade to read, and it didn’t disappoint. It’s a moving and delicate told narrative of the siege of Sarajevo, that perhaps wasn’t best served by its publication date just as something horribly similar was happening in and to Ukraine. Finally, 99 Interruptions is the latest slim missive from Charles Boyle, who published my Covid poem Spring Journal in his CB Editions. It sits alongside his pseudonymous By the Same Author as a perfect short book – with the same proviso that it’s so damned slim that it’s easy to lose. And indeed barely a month after buying it I already can’t find it to put in the photo. No matter. I’ll find it, months or years hence, by accident, and enjoy rereading it all the more for that.

For various reasons, this was a strong year for me for successfully finishing fat chunky classics that I’d tried and failed to read in the past: the kind of book I usually can’t read unless I can organise my life around it.

Continue readingOccasional review, of sorts: Dance Move, by Wendy Erskine

Dance Move is the second story collection from Wendy Erskine, following Sweet Home, which had some killer stories in. Dance Move is a more consistent and impressive collection, I think. There are some stone-cold classics in it, five at least that I feel I will be reading for the rest of my life, and certainly none that don’t leave an impact.

There are three things that impress and astonish me about Erskine’s writing, and that’s what I’m going to write about in this blog post, which isn’t really a review. (There’s a single spoiler right towards the end).

So, here’s what I love about Erskine’s stories:

i) the ‘realness’ of the people that she writes about.

I want to say you can barely call them ‘characters’, they’re so real, and yes I know that sounds cheesy. But they are the kinds of people you simply don’t read about in most contemporary literature (or not the literature I read, anyway). They make most characters in books look like they’ve either been put there for a reason – because the writer wants to make a point: character as sock-puppet or a straw man – or else they’ve been put there for no reason at all: the writer can’t imagine anything other than a faceless avatar of their own desires and fears.

Erskine’s characters aren’t like this. They are the reason why people mention Chekhov around her name. The characters are ‘ordinary’, but not in a fill-the-blanks way, or a central casting misfits way (like those model agencies that recruit ‘interesting-looking’ ugly people), but in an organic, from-the-inside-out, seemingly verifiable way. Because – cheesy again – nobody in real life is entirely ordinary. They’ve all got some weirdness going on. That ordinary weirdness is what Erskine’s characters have got.

ii) the very un-Chekhovian twists she gives her narratives.

The gun not hanging over the mantlepiece, but in the attic. (And you can be damn sure that if the gun’s going to be fired, it’s not because Chekhov said so.) The faded pop star’s call out of the blue for one last gig. The sister/sister-in-law’s mega-expensive party. These interventions hover around the surreal, while remaining entirely believable. I don’t mean formally or programmatically surreal, but surreal in the way they affect the characters’ lives. They are at once overwhelmingly weird, and able to be taken in the stride. They are surreal in context, not form.

And iii) the way she ends her stories.

She ends her stories brilliantly. You are so immersed in these characters’ lives (that Chekhov thing again) that you want to stay with them, but the deftness of the narrative interventions means that the stories aren’t wedded to plot, so can’t end with a traditional narrative climax or denouement.

(As David Collard said, in response to my original tweets, “Wendy Erskine’s stories don’t end, they simply stop” – which is so true. Perhaps it would be even better to say, they don’t finish, they simply stop.)

So how does she end them? She kind of twists up out of them, steps out of them as you might step out of a dress, leaving it rumpled on the floor. In a way that’s the true ‘dance move’: the ability to leave the dance floor, mid-song, and leave the dance still going.

Take the story ‘Golem’, definitely one of my favourites in the collection. It’s a story that does everything Erskine’s stories do. It densely inhabits its characters’ lives, and it has its comic-surreal interior moments, but most incredibly of all, it manages to end at the perfect unexpected moment. The story goes on, but the narrative of it ends. It departs, exits the room, taking us with it.

Perhaps the best way to put it is that you feel that, yes, the characters are ready to live on, and yes, you’d be ready to keep on reading the prose and the dialogue forever, but no, you wouldn’t want the stories themselves to last a single sentence longer. In this she’s the opposite of Alice Munro, who has the miraculous ability to extend her stories beyond where you think they surely must end. (Think ‘The Bear Came Over the Mountain’, or the incredible ‘Train’, from Dear Life.)

(NB, Wendy talked at her Social reading about ending stories, and it was great, and I thought I’d taken some notes, but I don’t think I did, so some of this is probably stolen from her. The only note I did take, I now see, is “against central casting”, which I now see I did steal. So it goes.)

In fact there’s one story in Dance Move where I wanted Erskine to ‘go Munro’, to stretch the possibilities of narrative: the opening story.

[Mild spoiler follows]

…

…

‘Mathematics’ introduces us to Roberta, a cleaner, likely cognitively impaired after a childhood accident, and happy enough in the circumscribed world of her job and life. (So far, so Chekhov.) Then, on a job, she discovers a primary school-aged girl in a hotel room, abandoned by her mother.

Six pages in, and Erskine has blown the floor out from under her story. Roberta tries to return the girl to her mother, via her school, but ends up looking after her. The ‘stakes’, for a story by Wendy Erskine, are incredibly high. So much could go wrong. We are so willing them to go right. Erskine has done something she doesn’t normally do: she has reached up out of the page, grabbed me by the hair and pulled me down into the story, forcing me to connect emotionally with the story. Normally she is too cool for that. (And that’s fine. I like her for that.)

And the story succeeds. Erskine pushes it just far enough, and then she does her brilliant effortless thing of deftly stepping out of it, ascending, quitting the room, leaving the dress on the floor, giving just enough for us to be sure that Roberta will go on with the narrative, on our behalf.

But, BUT, I wanted, I really wanted the story to continue, and for the floor to be blown out again. I wanted that rush again. Damn.

Thanks to Picador for the original proof copy of Dance Move. I was very happy to purchase my own copy of the hardback at Wendy’s brilliant reading at The Social, London, last week, though I had to leave before I could ask her to sign it.

Books of the year 2021

Here then are my best books of 2021 – which I’m limiting to books published in that year.

(Of books read for the first time and not published this year that I loved, I’d mention Sandra Newman’s wondrous The Heavens, Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea, M John Harrison’s Climbers and The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin.)

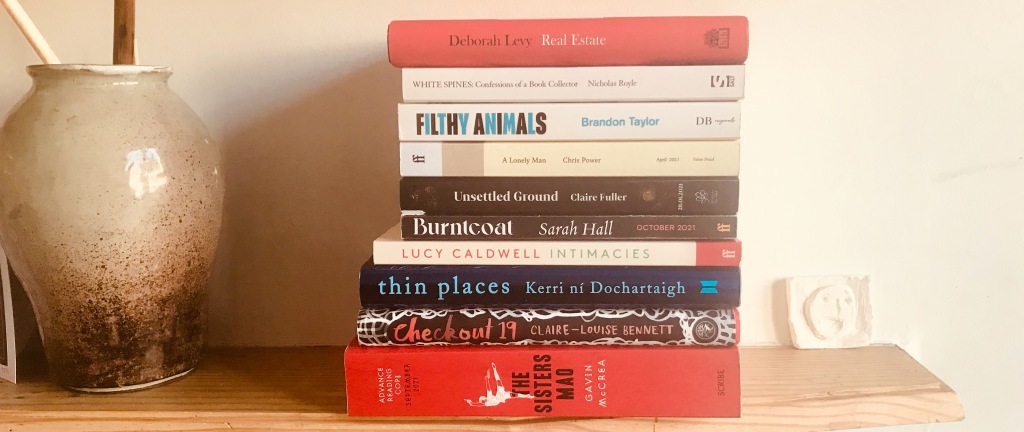

Looking at this stack, I see some powerfully good writing, some fine novels and short story collections and memoirs variously entertaining (Royle) and painfully exposing (Dochartaigh). Overall, it seems quite a middle-of-the-road selection, and if it seems to me slightly disappointing then perhaps that’s because all but one of the books are by writers I have already read, and so fully expected to enjoy. (Some of the writers, it has to be said, I know personally to a greater or lesser degree: Claire Fuller, Gavin McCrea, Chris Power, Nicholas Royle.)

So let’s say it wasn’t particularly a year of great discovery for me, which is a shame, and something that only really occurs to me as I write this round-up. Books can offer reassurance and comfort, and they can offer the thrill of the new. They are something you can settle into, or something that can unsettle you as it broadens your understanding of the world, and of reading as an endeavour and an experience. Newman’s The Heavens – the only one of those four ‘old’ books mentioned above that was by a new-to-me writer – surprised me as it unfolded, which is perhaps even more rare than surprising you from the off, with a rollicking premise or an unprecedented, irrepressible voice.

The one new-to-me writer on the ‘best of new books’ pile is Kerri ní Dochartaigh, whose memoir Thin Places I read in its entirety on the penultimate day of the year – so it’s possible that it benefits from recency. I didn’t completely love it from the start – there is a tendency, especially in its prologue, towards purple prose, and imagery that seems to be scattered into the prose too incautiously, like herbs in cooking – but it settles into its telling and the rationale of its narrative approach becomes more convincing the clearer it becomes.

The book is the story of a life lived under the shadow of the Troubles and the trauma induced by it, even when the author flees from her home town of Derry. She has a petrol bomb thrown through her bedroom window at the age of 11, her best friend is brutally murdered at the age of 16, her family breaks up and disintegrates, she experiences abusive relationships, addiction and suicidal thoughts. All of this is approached through what might be termed nature writing, as is common elsewhere, but this is done very much in the abstract, through the experience of remembering or recasting experience, rather than trying to take us through the experience as they might have happened. It is contemplative, rather than immersive. It helps, too, that Dochartaigh frames her story through a consideration of the damage that Brexit has done and is still doing to Northern Ireland. She looks outward, and onward, as well as inward, and back. There is repetition in the prose, but this takes the form of slight, extended echo, rather than insistent stuttering. If the writing is intended or effected as a process of healing, then that is because she uses language to stitch sentences – not to close wounds but to fashion bandages. You can see the work the words are doing.

The novel that surprised me the most – that felt most like a discovery – was Claire-Louise Bennett’s Checkout 19, which weaves and leaps with the strangeness of its voice: weirder and more vivacious I think than in Pond, her debut. It is a – possibly – autofictional account of a life lived in thrall to books, with quite simple anecdotes put through the wringer of this way of telling: swerving and recursive, like a childish Beckett making itself sick on sweets. This (non-) story then takes a capricious and absolutely unpredictable left-turn into an account of a ludicrous fictional character called Tarquin Superbus. I said in my original Twitter response that it left me in a state of energised perplexity – “I want to read it again, to see if I can understand it. But I don’t want to understand it” – and although I haven’t yet reread it, I have picked it up and glanced at it, and I do still very much want to reread it.

For the first time in 2021 I built a Twitter thread responding to all the books I finished (you can start it here), with the idea that this would help me with my monthly reading round-up blog posts, though unfortunately it replaced them rather than aided them. I only got as far as May, and then stopped. There were of course reasons for this, but I’m not yet sure how I will proceed next year.

As I’ve said before, this thread, and those posts, only offer a partial account of my reading: they are the books I read from cover to cover, and there are plenty of books I thoroughly enjoyed that I didn’t read completely, most obviously essays and short stories. It is noteworthy that the two short story collections that show up in this pile are ones that lend themselves to reading in full: Brandon Taylor’s phenomenally good Filthy Animals because of the linked stories following a trio of characters that thread through the book, and Lucy Caldwell’s Intimacies because of a more subtle narrative development that means the stories seem to kind of drift into autofiction towards the end, or rather seem to abandon plot development for a more thematic cluster of concerns. Read out of sequence they might seem rather the less for it. I wrote about Caldwell’s book here.

The continuation of my A Personal Anthology project (now approaching two thousand individual short story recommendations) means that I read lots and lots of short stories, but these rarely get mentioned. It would be great to think of a way to make this happen.

My job teaching Creative Writing at City, University of London, means that I also read a lot to work out what books I want my students (undergrad and postgrad) to be reading. This means I half-read a lot more books than I read in full. I half-read a lot of creative non-fiction this year, as I worked up to the launch of the MA/MFA Creative Writing, with its non-fiction strand. You can read about my selection process here.

I’m starting 2022 with a side-project to read Finnegans Wake a page a day in a group read organised by Paper Pills aka @ReemK10, and I have one other idea that may or may not come to fruition. Looking at my 2021 reading I feel the lack of a big classic in there – a Middlemarch, Proust or Magic Mountain. Another Mann is a possibility (Buddenbrooks or Joseph and his Brothers), and with every year that passes the fact of not having read Anna Karenina seems to loom more darkly. Two immediate work reading projects mean that I can’t think about that now.

Finally, my reading is always at odds with my writing. I am close to finishing a first draft of a novel that should have been done a year ago, but then I tell myself that I wrote a book-length poem in 2020 (Spring Journal, which you can still buy of course from the publisher, the brilliant CB Editions), and I launched a postgraduate degree in 2021, so perhaps 2022 will be the year it gets submitted. 2021 did also see the shortlisting of a story of mine – ‘A Prolonged Kiss’ – for the Sunday Times Audible Short Story Award, which was thrilling. You can find the story in its initial publication in The Lonely Crowd, and listen to it read brilliantly on Audible.

Instead of June reading 2021: the fragmentary vs the one-paragraph text – Riviere, Hazzard, Offill, Lockwood, Ellmann, Markson, Énard etc etc

This isn’t really going to function as a ‘What I read this month’ post, in part because I haven’t read many books right through. (Lots of scattered reading as preparation for next academic year. Lots of fragmentary DeLillo for an academic chapter I filed today, yay!)

Instead I’m going to focus on a couple of the books I read this month, and others like them: Weather by Jenny Offill, and Dead Souls, by Sam Riviere. I wrote about the fragmentary nature of Offill’s writing last month, when I reread her Dept. of Speculation after reading Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This (the month before), all three books written or at least presented in isolated paragraphs, with often no great through-flow of narrative or logic to carry you from paragraph to paragraph.

Riviere’s novel, by contrast, is written in a single 300-page paragraph, albeit in carefully constructed and easy-to-parse sentences. And, as it happens, I’ve just picked up another new novel written in a single paragraph – this one in fact in a single sentence: Lorem Ipsum by Oli Hazzard. I haven’t finished it, but it helped focus some thoughts that I’ll try to get down now. These will be rough, and provisional.

Questions (not yet all answered):

- What does it mean to present a text as isolated paragraphs, or as one unbroken paragraph?

- Is it coincidence that these various books turned up at the same time?

- Does it tell us something about ambitions or intentions of writers just now?

- Are fragmentary and single-par forms in fact opposite, and pulling in different directions?

- If they are, does that signify a move away from the centre ground? If not, what joins them?

Let’s pull together the examples that spring to mind, or from my shelves:

Recent fragmentary narratives:

- No One is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood (2021)

- Weather (2020) and Dept. of Speculation (2014) by Jenny Offill

- Assembly by Natasha Brown (2021) – in part, it jumps around, I haven’t read much of it yet.

And further back;

- This is the Place to Be by Lara Pawson (2016) A brilliant memoir written in block paragraphs, but allowing for a certain ‘through-flow’ of idea and argument.

- This is Memorial Device by David Keenan (2017) – normal-length (mostly longish) paragraphs, but separated by line breaks, rather than indented.

- Satin Island by Tom McCarthy (2015) – a series of long-ish numbered paragraphs, separated by line breaks.

- Unmastered by Katherine Angel (2012) – fragmentary aphoristic non-fiction, not strictly speaking narrative.

- Various late novels by David Markson, from Wittgenstein’s Mistress onwards

- Tristano by Nanni Balestrini (1966 and 2014) – a novel of fragmentary identically-sized paragraphs, randomly ordered, two to a page. The paragraphs are separated by line breaks, but my guess is that the randomness drives the presentation on the page.

Recent all-in-one-paragraph narratives:

- Lorem Ipsum by Oli Hazzard (2021)

- Dead Souls by Sam Riviere (2021)

- Ducks, Newburyport by Lucy Ellmann (2019)

And further back:

- Zone (2008) and Compass (2015) by Mathias Énard

- Various novels by László Krasznahorkai, of which I’ve only read Satantango (1985) – a series of single-paragraph chapters.

- Various novels by Thomas Bernhard, of which I’ve only read Correction (1975) and Concrete (1982)

- The first chapter of Beckett’s Molloy (1950) is a single paragraph, as is the last nine tenths of The Unnameable(1952)

- The final section of Ulysses, by James Joyce (1922)

So, my thoughts:

Continue readingHow should one read a short story collection? On ‘Intimacies’ by Lucy Caldwell

So Lucy Caldwell’s Intimacies was one of my May reads, but I’ve split off into a separate blog to write about it, because I found it so interesting. I’ll say straight out that it is a great collection of stories, which much of the same calm, wry, politically and socially observant writing as her debut collection, Multitudes, but the reason I want to write about it (and not just it) is something different from just the quality.

I’ll also say second out that I met Lucy last year, when she kindly agreed to talk with me, and Michael Hughes and David Collard, for the Irish Literary Society about my poem Spring Journal and its connection to Louis MacNeice, of whom she is a great fan, as evidenced by her Twitter handle @beingvarious, and in fact the great anthology of contemporary Irish short stories of the same title that she edited; and she was kind enough to say some words about the book, which were used for a blurb. So I am in her debt for that.

And but so…

Short story collections.

I own maybe 100 single-author individual collections, as opposed to anthologies or Collecteds, but I’ve got no idea how many of them I’ve read in their entirety. I do read plenty of short stories, not least because of A Personal Anthology, the short story project I curate, which pushes me weekly in all sorts of directions, some of them new, some of them old, but when I do read stories I mostly read one, two or at most three stories by a particular author at a time.

This partly comes down to the practicalities of reading. A short story you can read in the bath, and a long decadent bath with bubbles and candles might stretch to three or four, depending on the writer. Or, as I have done this afternoon, sitting outside in the garden, reading ‘Heaven’, the final story in Mary Gaitskill’s seminal Bad Behaviour, a story which… but now’s not the time.

But seriously: what a story!

What I generally don’t do is read collections in order, from start to finish. I appreciate that this might be annoying for authors, who presumably put some effort into sequencing their collections, but a collection isn’t like a music album – not quite – which lends itself almost exclusively to listening in order. (I remember when CD players came out, and the novelty of random play. It’s not something I would ever do now, and I find it annoying that it seems to be a default setting on Spotify.)

The reason why I don’t tend to read collections in order, is partly because I like reading stories in isolation. I think it’s a Good Idea. If – to be reductive about it – novels are a writer doing one big thing, slowly, and stories are writers doing a small thing, over and over, then there is a risk, in reading a collection in one go, of seeing a writer repeat themselves. After all, they most likely wrote the stories to be read individually. Read me here, doing my thing, in The New Yorker. Read me here, doing my thing again, in Granta. And here I am, doing something similar but different in The Paris Review.

Some collections of stories are just that: agglomerations of pieces that have individual lives of their own, published here and there, and their coming-together is primarily a commercial rather than an artistic act. Some collections are more integrated than that, more self-sufficient or autarchic, having no particular dependence on anything outside of its little biosphere.

As I tweeted about the theme of this blog, John Self mentioned David Vann’s Legend of a Suicide and Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son as two collections that operate like this, that need to be read in order. He’s right, though annoyingly I don’t have either to hand. The Vann I think is in a box in the loft, and I’ve never owned a copy of Jesus’ Son, despite it being a touchstone of sorts. Claire-Louise Bennett’s Pond is another example, with its famous ambiguity as to whether it’s a novel or a collection of stories, but that has the oddity that I think you could read it in any order.

There must be others. I might think further and come back to this. You might have thoughts yourself.

So once you’ve leaned away from the idea of reading a collection in one go – to avoid the risk of diminishing marginal returns – then the need to read them in order seems somehow weaker. So that’s what I do. I take a collection down from the shelf, a new one or an old one, and I scan the contents page; I consider the titles; I look at the page-length. I make my choice.

Continue readingMay reading 2021: Offill, Machado, Murata, Slimani, Kristof, Spark

Seven books, mostly quite short. I re-read Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill for what was at least the third time. I think I picked it up as I’d been reminded of it by Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This, which I wrote about last month, and is written in a somewhat similar format. While the fragmentary form in Lockwood’s novel is clearly intended to represent consciousness fractured through Twitter and social media, Offill’s book is less online, and more about consciousness fractured through modern life in general. Offill is more constrained, more zen. The narrator’s brain has filtered the world. Lockwood’s narrator can’t filter the world, and insists on adding to it, interpreting it.

Lockwood’s book, as I said in my post, is unnerving, even enervating to read. Offill’s is restful, even when it turns dark.

Nevertheless, it’s odd that the book seems to lose its way after the halfway mark. It can’t do the melodrama it has promised, through its story of marital breakdown, but it performs a wonderfully neat pirouette to avoid the collision. This happens in the superb chapter 32, in which the narrator confronts her errant, adulterous husband and his ‘other woman’, but undermines her own description with a viciously precise creative writing commentary: “Needed? Can this be shown through gesture?”

The scene that follows reminded me of the equivalent one in Elena Ferrante’s Days of Abandonment. But, where that is brilliantly visceral, this one just crumbles. That said, I suppose the temporary ‘failure’ of the novel is justified by its premise. The narrator is somebody who needs to be in control. That’s what’s behind her compulsive marshalling of facts, which she parcels out in those fragmentary paragraphs. When she loses control, the narrative dissolves into a swamp of entropy and only gradually, and it’s not entirely clear how, works its way back out. She reads a self-help book about surviving adultery, which she sneers at, but which – maybe – helps.

For sure, this book is not a self-help book about fixing a collapsing relationship. For all the nuggets of wisdom it purportedly contains, it’s never clear how they do it, the two of them, the couple and their daughter, beyond moving to the country, the “geographic cure”, which seems a surprisingly old-fashioned resolution to such an untraditionally presented story.

It reminds me of one of my all-time favourite books: Wittgenstein’s Mistress by David Markson. Similar in the fragmentary form, similar in the obsessive relay of facts, and knowledge, and wisdom. (Rilke! The Voyager recording!) All of which is weaponised, and then irradiated. Literature as series of fortune cookies. Knowledge is reducible, and manageable, and transferable, and this is at once a good and a bad thing. (It reminds me, too, of Lucy Ellmann’s Ducks, Newburyport, which I never did/still haven’t finished.)

All three books, or four, counting Lockwood, though perhaps that one less, are about the uselessness of knowledge in the face of the world. Forgert Rilke, forget wisdom. If you want to save your marriage, simply move to the country, get a puppy, chop firewood. Which is lovely, but… really?

In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado is an eye-opening account of an abusive relationship that turns expectations of the sub-genre on their head. The formal invention is impressive and effective, but some things do get lost. The book is a persuasive account of a subjective experience – of being gaslit and abused – and what I missed as a reader was the objective dimension. The ‘woman in the dream house’ – the abuser – remains something of an enigma. What was she like? What was her problem? Of course, this lack, this absence, may well be partly due to the ethical and legal aspect of memoir writing. The ‘woman’ presumably must remain vague in some aspects so she remains unidentifiable, and can’t sue. (I covered some of this in my review of Deborah Levy’s Real Estate.) For all its inventiveness, the book delineates the limits of what memoir can do.

I enjoyed Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata, which I read after listening to Merve Emre and Elif Batuman discussing it on the Public Books podcast. I didn’t agree with everything they said, but I was intrigued in particular about their description of the book as ‘an adultery novel’, i.e. a story build on a simple narrative model of thesis – anthesis – synthesis. I was preparing a workshop on plot and structure in novel-writing (for London Writer’s Café, hopefully more to come in the Autumn!) and thought it would be interesting to see how the novel managed this.

Continue readingMarch & April Reading 2021: Lockwood, Moore (Lorrie), Levy, Moore (Susanna), Nelson, Garner, Hall, Musil

At the start of 2021 I began an open-ended Twitter thread listing and commenting on my reading as I finish each book. This was supposed to help with these monthly round-ups, to save time, which clearly didn’t work at the end of March, as I didn’t post a round-up at all. So, for this two-month round-up I’ll be picking and choosing and expanding on those thoughts on some but not all of what I’ve read, rather than going through it doggedly.

It took me a bare couple of hours to read No One is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood, and I’ve spent at an hour elsewhere reading reviews and thinkpieces about it. Which only goes to show, as someone on here pointed out, that it’s the least well-titled book of the year. Unless she means it ironically. Or post-ironically. Or whatever.

I did really like the book, but also I found it exasperating and even anxiety-provoking. The short, fragmentary sections are clearly designed to mimic Twitter, but unlike Twitter you seem to have to read every one of them, as if there is something to ‘get’ from each of them.

This was confusing. On Twitter, after all, you skim through a dozen tweets in as many seconds before you deign to give one your more considered attention, sometimes scrolling back up to read one you initially skimmed over. Your micro-decisions about what to give your attention to are affected by names, and digital paratexts like avis and retweet and like counts. You don’t get that with tweet-length paragraphs on the page of Lockwood’s novel, but equally the usual narrative paraphernalia that allow you to speedily and efficiently navigate a story are also absent. Even Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation had more flow and propulsion across its narrative islets than this.

Of course you acclimatise, and for a while you drift through the novel, picking up little dopamine hits for identifying memes and moments. The incest advert. The plums poem. But the pace of reading picks up, and the drifting becomes sliding, and it takes a great line to slow you down. Thankfully there are plenty of great lines.

Then Something Happens, plot-wise, and this is where the real challenge for the novel lies. Having established a vehicle of utter affectlessness in the first half (even while critiquing and despairing over the same), can it step up and deal with a subject that demands genuine emotional engagement?

Well the answer is no, for me at least. The emotion is there, and if you’ve read the interviews and perhaps even if not you’ll know it’s real, but the novel simply cannot express it. None of the usual, traditional functional parts – the filters and switches – are present, or work as required. It’s as if the book knows it’s trapped, and wants to break out of the trap it’s built for itself – and that’s part of the project after all, that’s what so many of us want to know: is there a way through this way of being, that will lead to another, better one?

What’s missing is the connective tissue. Now, the online world, when we are in it, does contain a connective tissue, of sorts: what gets called ‘the discourse’ (as in: the discourse is particularly toxic this morning). The discourse is the suspension (in the scientific sense) in which the individual tweets float, and take their context, and to which they all, infinitesimally, add.

The point of the novel seems to be that this way of connecting with the world is leaving us adrift and unfulfilled. But when Lockwood gets to the second part of the novel, when tragedy drags her away from the Portal and immerses her in real life, the novel doesn’t change. It’s still written in that atomised, fragmentary style. Is that because this is the only way the narrator can think the world into being? Or is it intended to show the inability of ‘interneted narrative’ to represent the deep continuum of real life? Would it have been a failure of form if Lockwood had ‘reverted’ to a more traditional narrative style to cope with what happens ‘off-screen’?

No One is Talking About This is a tragedy of form, because although it allows me to empathise with the narrator when she is feeling sad about her unconnectedness, it fails to make me empathise when she suffers genuine tragedy. And it’s the form that engineers that failure.

Anagrams by Lorrie Moore was an impulse re-read. It has such a wonderfully idiosyncratic form – four short stories followed by a novella, all featuring the same three characters in different versions and permutations: anagrams of themselves, in other words. Here’s what I said when I read it for the first time on holiday, back in 2013. “These people are us! They are us squared!” is clearly me trying to channel Moore. But it’s true that Moore does use humour to set up devastation. And in fact I’d forgotten quite how bleak the end of Anagrams is.

Continue readingOccasional review: Real Estate, by Deborah Levy

I remember the first Deborah Levy book I read, and where I acquired it. It was Beautiful Mutants, in its splendid Vintage paperback edition, with its Andrzej Klimowski collage cover, and I bought it from a remaindered bookshop in Tenterden in Kent, where my grandmother lived. Tenterden had a good old-fashioned sweetshop, and it had this bookshop, with two low-ceilinged rooms, at the far end of the high street, which I used to try to try to get to whenever we visited.

I’ve always preferred bookshops to libraries. I know how that sounds, and I do love libraries, but it’s true. Books are things I want to acquire. Reading them is not enough; I need to have them. There are reasons behind this beyond mere materialism: I want to be able to read the book in my own time; I want to be able to put it down and pick it up again; I want to be able to write in it; I like to read books I believe I will want to read again; I want it there in my house to remind me I’ve read it, so I can reread it if I want. And yes, book is a statement about the person who buys it. Books are part of the way I interact with the world. This is the way we make culture out of art, by sharing it, and sharing through it.

I love new bookshops, and I love secondhand bookshops, and I love the book sections in charity shops, and each of these venues offers something slightly different as an experience to browser and buyer, but I have always had a fondness for remaindered bookshops.

Remaindered bookshops (good ones – are there still good ones? perhaps there were more of them in the days of the Net Book Agreement) give you two fine things: a sense of getting something new, for cheap, a bargain; and a sense that you’re getting something that perhaps has slipped under the radar, that didn’t sell as well as the publishers thought, that is likely to be something you haven’t heard of, that you might want to take a punt on, that is perhaps not quite first rate, but all the more interesting for that, a potential future cult classic.

I can’t remember all the other books I bought from that shop in Tenterden, except for a book of the graphic design of Neville Brody, and a hardback collection of letters written to George Bernard Shaw by ordinary members of the public. I don’t think I have either of those two books any more, but I do have the Levy.

(How I wish had written in the front of all my books the details of where I got them. Imagine the Perecesque autobiography those details would tell.)

I do know where I got the newest Deborah Levy, which was sent to me by the publisher. Real Estate is the third of Levy’s ‘living autobiographies’, sort of diary-cum-memoir-cum-essays. I read the first, Things I Don’t Want to Know, and reviewed it for The Independent when it came out, in 2013, published by Notting Hill Editions, but I don’t know where my copy is. Either I reviewed it from a digital copy, or I lent or gave it away. I certainly wouldn’t have charity-shopped it. I didn’t read the second instalment, The Cost of Living, but having now read Real Estate, I’ve ordered a copy.

Real Estate I enjoyed hugely, and more than I was expecting to. I’ve been reading Levy since the early 90s, and loved Beautiful Mutants and Swallowing Geography, though not so much Billy and Girl, I seem to remember. (I can’t find my copy of that either, to update my thoughts.) I was less taken with her second wave or renaissance books, Swimming Home, Black Vodka (stories) and Hot Milk. I felt she had toned down her exuberance but lost the craziness – the burning zoo, the “Lapinsky is a shameless cunt” – that seemed to carry crackling danger in every sentence, every page. The newer novels were tilted off their axis, certainly, but either didn’t entirely find their footing or didn’t take to the air.

I don’t remember that much about Things I Don’t Want to Know, and will reread it, to see how the three books operate together, but here’s what I think about Real Estate: it’s a swift, sure, clean, clear account of and reflection on Levy’s world, post-success, post-marriage, with both of her daughters now left home, leaving her to consider how she will make the most of her fully independent life at an age (she turns 60 in the course of the book) when one might hope she can fully capitalise on her promise, and success.

The title refers to the question of house ownership, as a dream and as an anchor, an aspect of self-identity and self-worth. During the book Levy writes in two sheds in two different people’s gardens, packs up her dead stepmother’s apartment in New York, travels to Mumbai for a literary festival, and decamps to Paris for a nine-month fellowship; she visits a friend in Berlin, and rents a house in Greece to write in for the summer. She is also haunted by the family house where she was once happy, and then unhappy.

All the while she cultivates her dream of a “grand old house with a pomegranate tree in the garden”, furnishing it in her mind with articles and objects she has accumulated over her life that would deserve their place in this ideal dwelling.

If Levy is playing ‘dream house-hunting’ then that’s fine with me. In a way, she herself is living a dream that belongs to many of the rest of us: a writer comes into well-deserved success after early years of promise, and middle fallow years, finding the literary superstructure bending itself as if by magic around her and to her and lifting her up. (Mumbai… Paris… Greece… what writer wouldn’t dream of that! What writer wouldn’t at least consider the painful end of a marriage a fair psychic payment for this other daydream…)

She uses the house metaphor to bring in other themes and issues: the difficulties female writers face, the lack of self-knowledge of male writers who turn up at festivals with their wives in tow as assistants, who corner you at parties with self-centred wining.

Continue reading