Tagged: Elena Ferrante

May reading 2021: Offill, Machado, Murata, Slimani, Kristof, Spark

Seven books, mostly quite short. I re-read Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill for what was at least the third time. I think I picked it up as I’d been reminded of it by Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This, which I wrote about last month, and is written in a somewhat similar format. While the fragmentary form in Lockwood’s novel is clearly intended to represent consciousness fractured through Twitter and social media, Offill’s book is less online, and more about consciousness fractured through modern life in general. Offill is more constrained, more zen. The narrator’s brain has filtered the world. Lockwood’s narrator can’t filter the world, and insists on adding to it, interpreting it.

Lockwood’s book, as I said in my post, is unnerving, even enervating to read. Offill’s is restful, even when it turns dark.

Nevertheless, it’s odd that the book seems to lose its way after the halfway mark. It can’t do the melodrama it has promised, through its story of marital breakdown, but it performs a wonderfully neat pirouette to avoid the collision. This happens in the superb chapter 32, in which the narrator confronts her errant, adulterous husband and his ‘other woman’, but undermines her own description with a viciously precise creative writing commentary: “Needed? Can this be shown through gesture?”

The scene that follows reminded me of the equivalent one in Elena Ferrante’s Days of Abandonment. But, where that is brilliantly visceral, this one just crumbles. That said, I suppose the temporary ‘failure’ of the novel is justified by its premise. The narrator is somebody who needs to be in control. That’s what’s behind her compulsive marshalling of facts, which she parcels out in those fragmentary paragraphs. When she loses control, the narrative dissolves into a swamp of entropy and only gradually, and it’s not entirely clear how, works its way back out. She reads a self-help book about surviving adultery, which she sneers at, but which – maybe – helps.

For sure, this book is not a self-help book about fixing a collapsing relationship. For all the nuggets of wisdom it purportedly contains, it’s never clear how they do it, the two of them, the couple and their daughter, beyond moving to the country, the “geographic cure”, which seems a surprisingly old-fashioned resolution to such an untraditionally presented story.

It reminds me of one of my all-time favourite books: Wittgenstein’s Mistress by David Markson. Similar in the fragmentary form, similar in the obsessive relay of facts, and knowledge, and wisdom. (Rilke! The Voyager recording!) All of which is weaponised, and then irradiated. Literature as series of fortune cookies. Knowledge is reducible, and manageable, and transferable, and this is at once a good and a bad thing. (It reminds me, too, of Lucy Ellmann’s Ducks, Newburyport, which I never did/still haven’t finished.)

All three books, or four, counting Lockwood, though perhaps that one less, are about the uselessness of knowledge in the face of the world. Forgert Rilke, forget wisdom. If you want to save your marriage, simply move to the country, get a puppy, chop firewood. Which is lovely, but… really?

In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado is an eye-opening account of an abusive relationship that turns expectations of the sub-genre on their head. The formal invention is impressive and effective, but some things do get lost. The book is a persuasive account of a subjective experience – of being gaslit and abused – and what I missed as a reader was the objective dimension. The ‘woman in the dream house’ – the abuser – remains something of an enigma. What was she like? What was her problem? Of course, this lack, this absence, may well be partly due to the ethical and legal aspect of memoir writing. The ‘woman’ presumably must remain vague in some aspects so she remains unidentifiable, and can’t sue. (I covered some of this in my review of Deborah Levy’s Real Estate.) For all its inventiveness, the book delineates the limits of what memoir can do.

I enjoyed Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata, which I read after listening to Merve Emre and Elif Batuman discussing it on the Public Books podcast. I didn’t agree with everything they said, but I was intrigued in particular about their description of the book as ‘an adultery novel’, i.e. a story build on a simple narrative model of thesis – anthesis – synthesis. I was preparing a workshop on plot and structure in novel-writing (for London Writer’s Café, hopefully more to come in the Autumn!) and thought it would be interesting to see how the novel managed this.

Continue readingBooks of the Year 2020

The best books of the year – or rather the books that gave me the best reading experiences. Meaning the deepest, highest, widest, closest, most pleasurable. In all the strange ways we measure pleasure.

Well, I’d better start by saying I finished my complete, first reading of Proust – which I’d started on 1st January 2019 – on 31st May 2020. The plan had been to read the whole thing in a year, but by October 2019 I was still only on volume 4, and the last date that year (I took to writing the date in the margin to mark where I finished reading each day) was 21st October, halfway through that volume. I picked it back up in February 2020, beginning again at the start of vol 4, and made good progress through lockdown. All along I jotted thoughts and posted screenshots on a dedicated Twitter account (@proustdiary), and if I had the time I would try to scrabble together and collate these into something more coherent. It was a major reading experience, yes, full of great highs but also full of longeurs and swampy sections to trudge through. Don’t go reading it thinking it’s like other novels. It’s not.

Other major reading experiences of the year from books not published in the year:

- Middlemarch, read for the first time, on holiday in that odd distant summer window when I was lucky enough (for lucky read privileged) to be able to spend 10 days on a Greek island. Not just a wonderful, exemplary novel, it is also a vindication of the very idea of the Victorian novel, of what it can do: stolid realism, intrusive omniscient narration, all the things we like to think we do without in our literary style today.

- The Third Policeman. I’d tried At Swim, Two Birds before, more than once, and never got far with it, admiring its precocious undergraduate wit without being convinced that it would develop into anything more worthwhile. This one, though, tugged at me from the first pages, and delivered, in all dimensions. The spear, and the series of chests! The lift to the underworld. The ending! My god, the ending. Let me kneel before the scaffold, which must be the best piece of tactical diversionary business in the history of literature. Read it, then let me buy you a beer to talk about it. (By the bye, I’ve been reading Kevin Barry’s Night Boat to Tangier, on and off, this last month or so – for so slight a book, it’s taken a long time to get through – and you think: oh man, you have talent, but you don’t have that bastard’s wicked spear, so sharp it will cut you and won’t even notice. “About an inch from the end it is so sharp that sometimes – late at night or on a soft bad day especially – you cannot think of it or try to make it the subject of a little idea because you will hurt your box with the excruciaton of it.” Recommended to me by Helen McClory, to whom I am grateful.

- Midwinter Break by Bernard MacLaverty. My first by him. The kind of writing I feel able to aspire to. Precise building of characters in the round. All tilting towards a moment. That moment in the Anne Frank House. It made me reconsider VS Prichett’s line about a short story being something glimpsed out of the corner of your eye. That particular scene could have made a great short story, and it would have remained a glimpse. Sometimes, however, a novel can be a heavy and ornate or structurally robust frame or scaffold designed to hold a glimpse, and the glimpse hits home harder than it ever would at the length of a story.

- Autumn Journal. My true book of the year. From March to August I read it every day, as I was writing my own poem, Spring Journal, given out first on Twitter, and now published by CB Editions. I learned so much about metre, and rhyme, from immersing myself in it.

But, of books published this year:

The Lying Life of Adults by Elena Ferrante (translated by Ann Goldstein, Europa Editions, not pictured as lent out) was my novel of the year. Such a relief, to start with, that she was able to follow the Neapolitan Quartet, and with something that was neither a shorter version of those books, nor a return, quite, to the short vicious claustrophobia of the three brilliant standalone novels. It is perhaps less fully distinctive than any of those works – more similar, in scope, to what other people write as novels, but no less pleasurable for that. I read it, along with Middlemarch, on holiday, and it gave me the great pleasure of holiday reading, of allowing reading time to overflow the usually watertight boundaries of hours and activities, of blocking out the world. It’s strange, isn’t it, how we go to lovely places on holiday – places with great views, great landscape, and great climate – and read. I mean, you could lock yourself up in your bedroom and read, for a week, but you don’t. (If you can afford to, you don’t.) There must be something about the climate and landscape that improves the reading, or something about the reading that makes the landscape and climate more precious, for being ignored, or not being made the most of. The Ferrante reminded me of Javier Marías – who, incidentally, I had auditioned for taking on that same holiday, buying Berta Isla in anticipation, but I glanced at it a few times before setting off and, chillingly, found it utterly unappealing and most likely dreadful.

Similar in a way to Ferrante’s quartet was Ana María Matute’s The Island (translated by Laura Lonsdale), another essential discovery from Penguin Modern Classics. I reviewed it on this blog, here. As I say there, it was the incantatory aspect of the narration, calling back over the years to the lost friends, lost love, lost self, that stayed with me from reading it.

2020 saw the publication in translation of Natalie Léger’s The White Dress (translated by Natasha Lehrer, Les Fugitives), the third part of her trilogy of monograph-cum-memoirs that began – in English – with Suite for Barbara Loden, and continued with Exposition (those two were written and published in French in the opposite order). What a set of books these are! As strong on the furious waste of female artistic talent, and the general and specific ways that men, and male social and cultural structures, set out to achieve this end, as anything by Chris Kraus; as simply, naturally adventurous in its manner of navigating its different forms as Kraus or Maggie Nelson. Each book is brilliant, no one of them is put in the shadow by the other two, but the ending of The White Dress – this book is about Pippa Bacca, an Italian performance artist who was abducted, raped and murdered while hitchhiking across Europe to promote world peace – is as sickeningly powerful in its effect as the end of Spoorloos (The Vanishing). You feel helpless. I wrote more about The White Dress in a monthly reading round-up, before these petered out, here.

I chose Nicholas Royle’s Mother: A Memoir (Myriad Editions) and Amy McCauley’s Propositions (Monitor Books) as my books of the year for The Lonely Crowd. They’re both brilliant, and you can read my thoughts on them here.

Another memoir that I devoured, and that gave me tough minutes and hours of thinking and reflection, even as, on the page, it sparked and effervesced, was Rebecca Solnit’s Recollections of my Non-Existence (Granta). In a way it’s the opposite to Royle’s book, which is only ever caught up in the flow of time as if by happenstance. Royle’s mother happened to live through certain years, and be of a certain nationality and generation, so the exterior world does impinge, but impinges contingently. (The book is about personality, and how personalities bend towards, away from and around each other in a family.) Solnit’s book, by contrast, is absolutely caught in the flow of time. Solnit is who she is because of when she lived, and lives. In this it’s somewhat similar to Annie Ernaux’s superb The Years, which I wrote about here, and chose for my Books of the Year in 2018. And it’s as intelligent and insightful as Léger’s books, though Solnit has no reservations about writing about herself. (Léger, you feel, can only write about herself by way of writing about others. She is reticent, and so to an extent subject to the ego. Solnit writes memoir without ego.) This is certainly the book of Solnit’s that I’ve enjoyed the most.

From memoir to essays – and yes there is a lot of non-fiction on this list, among the new books I mean. I’m not sure why this is. There are other contemporary novels and short stories (in collections, journals, on their own) that I’ve read this year that I enjoyed, but none of them impacted on me as heavily as these books. Perhaps it’s because fiction is less concerned with its impact on the reader here and now, it drifts into the timeless time of world and story that must, perforce, be largely unlinked to the phenomenal world. By contrast, all these essays address me, here today, and demand something of me. (Incidentally, timeliness is not a guarantee of meaning. I tried reading Zadie Smith’s ‘lockdown’ essay collection Intimations, and found it rather insipid. It seemed like noodles and doodles, when Solnit, Léger and Ernaux, as good as sat me down and talked important things to me, things that needed to be said.)

I very much enjoyed Elisa Gabbert’s The Unreality of Memory and Other Essays (Atlantic), the essays of which seemed to spring from the world – they are about disaster, ecological crisis, terrorism, things that we know as it were unknowingly. They are unknown knows. The subjects seemed to be held still by Gabbert as if by force of will, in a way that seems different from the other non-fiction pieces mentioned here. They were not a natural outpouring or distillation of insight – as, for example, and famously, was Solnit’s brilliant ‘Men Explain Things to Me’ – but worked pieces, pieces Gabbert had to work at, to get right, topics she had to apply herself to in order understand them, to bring them under the law of her thought. She was forcing herself to think, and we were beneficiaries.

Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence (Fitzcarraldo) is a characteristically intelligent, urbane, distinguished set of essays that focus on particular writers by zooming in on – and then building out from – single sentences of their writing. They are master-classes, and they remind me of Clive James’s Cultural Amnesia, though that book ranged more widely (James ranged more widely, full stop). Suppose a Sentence is wonderful because what it offers is unapplicable. You can’t use it for anything else. Its lessons are oblique. It’s like a walking tour of a part of the city you’d never found on your own, and never will be able to again.

Exercises in Control by Annabel Banks (Influx Press) was perhaps the most interesting new collection of short stories I read this year. The stories are mostly short, and don’t try too hard to be polished or well-rounded, nor to be artfully extraordinary. But they grab you with their insouciance, their not-caring. The story ‘Rite of Passage’, with a girl (I should say ‘woman’) who crawls into hole in a rock on a beach on a date, was thrilling for its unpredictability. It didn’t quite have the courage of its convictions, in the end, but many of the stories left me feeling deliciously unmoored.

Finally, my other book of the year, it goes without saying, was The Snow Ball by Brigid Brophy, reissued by Faber, my favourite novel of one of my all-time favourite writers, who is hopefully becoming better known. This book was, to some extent, the model for my last novel, The Large Door, set, like Midwinter Break, in Amsterdam. I love The Snow Ball with a reader’s passion, that is say excessive, partial, formed by circumstance and transference.

- The following books were courtesy of the publishers: The Island, The Snow Ball, The Lying Life of Adults, The White Dress, Suppose a Sentence. Thank you to Penguin, Faber, Europa Editions, Les Fugitives and Fitzcarraldo.

Sally Rooney and the hardback/paperback dilemma (A Graphic Index Part IV)

I hadn’t read any Sally Rooney until a couple of days ago when I was reminded on Twitter that there was a story in a back issue of The White Review that features the two characters – Marianne and Connell – from Normal People, Rooney’s Booker-longlisted and roundly lauded second novel. (Interestingly, this is from 2016, before the publication of her debut, Conversations with Friends.)

I hadn’t read any Sally Rooney until a couple of days ago when I was reminded on Twitter that there was a story in a back issue of The White Review that features the two characters – Marianne and Connell – from Normal People, Rooney’s Booker-longlisted and roundly lauded second novel. (Interestingly, this is from 2016, before the publication of her debut, Conversations with Friends.)

I read it, and loved it.

Then this morning I decided to take the latest Granta magazine (‘Generic Love Story’) into the bath with me for a lazy Sunday morning read, and there she was again, in the form of an actual extract from the book. (You can read it online.)

I read it, and loved it too, and finished with teary eyes.

Although this isn’t the main point of this post, I’ll say briefly that my reasons for loving it are more or less the same reasons other people have mentioned in reviews and online: that Rooney makes you care about the characters, which is perhaps an unfashionable thing; but also she seems utterly contemporary. This comes partly in the depiction of contemporary attitudes – to relationships, to sex – or rather of the contemporary ways of conceptualizing attitudes that themselves are probably as old as the hills; and also partly in the smooth integration of contemporary technology etc into the narrative, but also in the way the prose seems alive to the texture of life today.

One example: in the Granta extract, teenage Connell’s mother puts the kettle on, something that has happened countless times in realist prose fiction since the invention of kettles, or realism, whichever came first, but this time we get this: “She laughed, fixing the kettle into its cradle and hitting the switch.” And I realise that’s the first time I’ve had a writer notice that that’s how kettles work these days. (Perhaps someone else has used it, but I missed it.) And if Rooney is noticing that, then what else is she noticing about modern life? The kettle moment is like a concrete token offered to reader that encourages them to believe that the more intangible things she’s noticing (do young people really think like that about sex?) are credible also.

Now as it happens I’m off out to my local bookshop shortly to buy a book as a present (in fact it may well be a copy of Conversations with Friends) and so I’m asking myself: should I get Normal People? I’m sure I’ll like it. There is also a definite thrill to buying a new book to read straightaway when I’m not exactly short of other books that I either want to read or feel I should.

But… here’s the thing: it’s hardback, and I don’t want to read Normal People in hardback. Nor do I want to have the hardback of Normal People on my shelves.

Why is this?

Well, there are bad and shallow reasons why I might feel this. She’s a female writer is the most obvious one, and I don’t want to accord her the status of hardback author. She’s a paperback writer, to quote George Harrison out of context. Do I think this? I hope not. Or rather: the status thing is true. Not everything is worth buying in hardback. But I hope that my measuring of her worth doesn’t involve sexism.

Let’s take a step back. Continue reading

January reading: Gide, Riley, Hoban, Thorpe, Melo, etc…

My month’s reading began with Russell Hoban’s Pilgermann and ended with First Love, by Gwendoline Riley, read in a day, started on the train to work, and finished – nearly – on the train home. I read the last five pages leaning over the kitchen counter, eating hobnobs. If it had been light I would happily have stood out on the street to finish it. How does it end? Unexpectedly, desultorily, off-handedly, as it proceeds. It is, I think, the second Riley I’ve read. It’s excellent: a sketch (not a portrait) of a toxic marriage, with the narrator’s other relationships – ranging from also toxic to just failing to simply meh – doodled in the margins. Looking at it now I feel there’s a real risk that, for all my pleasurable immersion in its slantwise take on life, it will evaporate from my mind, as, indeed has the other Riley I’ve read, Joshua Spassky. (Maybe I’ve also read Opposing Positions. I’ve definitely got it. This isn’t looking good.) So, here’s me telling to re-read First Love in five years’ time. Item: “a small, poxed mirror”. Item: “We walked up to the shops, into the throat of the wind.” Item: “Outside the sunset abetted one last queer revival of light.” Item: the handful of walnuts; those final, vituperative rants. If some novels are the equivalent of a nice cup of tea, this book is a cup of tea, spilled. Deliberately, and pointedly.

Hoban couldn’t have been more different. It’s as much an outlier in the Hoban oeuvre as Riddley Walker, which it follows. A middle-aged reel through the Middle Ages, it follows the man (and owl) Pilgermann through some kind of life, some kind of afterlife. It lifts itself into operatic riffs on various religious preoccupations; it’s got walking corpses and terrible battles and Jewish folklore. It starts better than it finishes, though it starts brilliantly. The idea of picking it up again, now, four weeks on, to work out what was going on in it, seems rather too tiring. I prefer his later, more obviously comic novels, that seem to carry themselves more lightly.

Black Waltz, by Patrícia Melo, translated from the Portuguese by Clifford E Landers, is a re-read. I’d been meaning to try it again. It’s a story of a man – a successful international conductor – unhinged by jealousy. With no apparent reason apart from his own delirium, he he decides that his younger wife, a violinist, is being unfaithful to him. He ends up losing much more than her. It’s smoothly gripping, and effectively guts the reader at crucial moments. It reminded me of the early standalone Elena Ferrante novels, especially Days of Abandonment.

My Name is Lucy Barton, by Elizabeth Strout. Well: it’s exquisitely written – but I wasn’t fully taken in. Something about the reticence, the distance with which emotions are held, and for what purpose, meant it didn’t work its magic on me as it has on others. I wonder if it’s something to do with American reticence, which has a slightly different tenor to British, or English, reticence. Perhaps Americans see it as less of an inherent national trait, puritanism aside, and so it tastes that bit more delicious to an American palate.

Seven Brief Lessons on Physics – a Christmas present from my sister – was a bit of a frustration. I mean, how many times do I have to read accounts of quantum physics, black holes and the rest of them, before I actually understand them? I don’t think it will ever happen. (It happened, once, briefly, watching Michael Frayn’s Copenhagen. I got it, I really did – with the way the characters walked across the stage representing the movement of quarks or whatever they are – but I lost it the moment I left the theatre.) It doesn’t help that Carlo Rovelli uses some hokey metaphors to try to explain his science. When he says that the elementary particles “combine together to infinity like the letters of a cosmic alphabet to tell the immense history of galaxies, of the innumerable stars, of sunlight, of mountains…” and so on, I just can’t see how that helps. That’s not how letters work, really, and I can’t imagine that that’s how elementary particles work either: placed in sequence to form clusters as much made up with reference to the letters that aren’t there as to those that are, these clusters then being themselves arranged in particular sequences, so as to suggest meaning. That’s how the universe is made? No, it’s not.

River (by Esther Kinsky, translated by Iain Galbraith) and Sight (by Jessie Greengrass) are there because of reviews, still forthcoming. An Account of the Decline of the Great Auk… was homework for that review. (Review links added, to The Guardian and The White Review)

Flight was (re)read for the MA Creative Writing module I’ll be teaching this semester. It’s a great blokey literary thriller, a little too on-the-nose in the way it looks for flight metaphors, but agreeably credible in its blend of mystery and violence, and its slow unfolding of human relations, and evocative in its description of the remote Scottish coastline.

Heinrich Böll’s The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum (trans Leila Vennewitz) was read as a palette cleanser, because it was so short. But, for a short book, it’s dicey to read, and not just because this old Penguin paperback is going at the spine. At this distance (it was written in 1974) its twin themes of sensationalist tabloid journalism and the furore around the Red Army Faction terrorist group don’t seem to carry equal weight. The journalism stuff seems heavy-handed, but also naïve by comparison with the way news organisations treat individual privacy today, while the terrorism, so much meatier as a theme, is treated less thoroughly. The documentary style is interesting, certainly, and it’s made me want to keep exploring Böll. His stories, apparently, are superb.

Another short book I (re)read in a day is André Gide’s Strait is the Gate, translated by Dorothy Bussy, who features in Kate Briggs’s fascinating book about translation, This Little Art. Picked up because its title accidentally mirrors the title of my current work in progress, it astonished me again with the pure music of its prose, and the aching passion of its story, melodramatic and melancholy at the same time. It’s the story of a young love destroyed by excess religious sense, that sees heaven only in self-denial. It made we well up, and as good as cry, twice. If you read Gide in French as a schoolchild (probably La Symphonie Pastorale) it might be time to pick him up again. I want to go on straight to another of his books. I’ll see what I have. This, though, is a sublime little book.

The stories (Chris Power, M John Harrison, Bridget Penney, in a lovely old Polygon edition) I’ve been dipping into and enjoying. I may write about them next month.

Also read, but not pictured: The Language of Kindness, the forthcoming nursing memoir written by my colleage at St Marys, Twickenham, Christie Watson. That made me well up more times than I care to remember. A stonkingly human book, brilliantly pitched and controlled.

Goodbye, January.

A short Ferrante-inspired reading list

Yesterday I was at the South Bank’s Women of the World festival, deputising as host for a book group that met to discuss Elena Ferrante’s marvellous second novel, The Days of Abandonment. Reading it again ahead of the weekend (the third time of reading), this remains, for me, one of the most visceral and eye-opening pieces of fiction of recent years.

The story, for those that don’t know it, is about a woman, nearing 40 and with two young children, who is walked out on by her husband, and the spiral of mania, hatred and despair this sends her into. The story is full of violence and passion – more is abandoned than just a wife – but it never loses its grip on language or narration. It is as much a philosophical novel, as a psychological one. It’s also got a sex scene in it that has made me look at my partner with new, fearful eyes – it’s entirely naked in the way that Kerouac meant when he titled Williams Burroughs’ novel for him: “a frozen moment when everyone sees what is on the end of every fork.” On the one hand, this is the book that should be given to every new husband, just on the off chance they might, one day, be tempted by a piece of young flesh. It shows what abandonment can mean to the person you not just betray, but drop: what that can do to the sense of self. On the other hand, for reasons I won’t spoil, this would probably be a bad idea.

Obviously one of the topics of discussion during the group was Ferrante’s anonymity, and the fact that it would be hugely surprising if this was allowed to last, and lo and behold when I got home, I found stories on the web informing me that an Italian journalist thinks he has unmasked her. Denials followed, from everyone concerned, but even if this particular journalist was wrong, it’s bound to happen at some point. Fuckers.

Rather than dwelling on that, however, I thought I’d share another topic of discussion in the book group, which was – as with any book group – other writers and other books that this particular writer or book brought to mind. Everyone present scribbled down these recommendations, but here they are for general information:

Another book about betrayal and the end of a marriage: Stag’s Leap by Sharon Olds (poetry: not the first time I’ve heard great things about this)

Another book written by an anonymous author: Salt by Nayyirah Waheed, an entirely absent author, though one with an active Twitter feed – a way of reaching readers while bypassing the usual literary rigamarole. Poetry, again.

An even more ambitious form of anonymity: Wu Ming – a group of anonymous Italian novelists who write and publish their works collectively under an assumed name. They previously operated as Luther Blisset, under which name they published the successful novel Q.

Another book about a female friendship: We racked our brains trying to think of other novels that rivalled the Neapolitan Quartet for its portrayal of a life-long female friendship, with all the love, affection, rivalry, tension and comfort that entails. Someone suggested The Grandmothers by Doris Lessing, a novella about two old friends who both fall in love with each other’s teenage sons – a brilliant sounding conceit, and definitely one I will be checking out. (It was filmed as Adore, aka Two Mothers, starring Robin Wright and Naomi Watts. In book form it is available as a standalone film tie-in, called Adore, or as the title story in a collection of four novellas, The Grandmothers.)

Another book about female friendship: Animals by Emma Jane Unsworth. I chipped in with Sula by Toni Morrison. Someone also mentioned A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara as a take on male friendships written by a woman – the reactions were the usual mixture when this book comes up.

Another book that treats violence against women: The Book of Night Women by Marlon James – the previous book by the author of the Man Booker-winning A Brief History of Seven Killings.

Another (female) Italian author to check out: Margaret Mazzantini. There was one Italian woman in the book group, and she explained how she was rather surprised when she first saw the attention that Ferrante got in the UK. She was well-known in Italy, she said, and well-regarded, but was not necessarily lauded and celebrated quite as she is here. She suggested Mazzantini as the one of the most popular contemporary novelists, whose new book always causes a stir. Currently available in translation: Twice Born and Don’t Move, with another book, The Morning Sea, coming out May 2016.

Elena Ferrante: Four ways in to the Neapolitan novels, and no way out

To Lutyens & Rubinstein last night to help launch the final instalment of Elena Ferrante’s quartet of Neapolitan novels, The Story of the Lost Child, along with Cathy Rentzenbrink (The Last Act of Love), Tessa Hadley (The London Train etc), and Susanna Gross, literary editor of the Mail on Sunday. We had a fascinating discussion, with help from the attentive audience, though as was pointed out by I think Cathy, this was largely because by the end we were less certain of our thoughts and opinions on the books and its author than we had been at the beginning.

I’ll say a little about my personal take on the books in a moment, but perhaps the best way of sharing something of the spirit and content of the evening would be to introduce the four passages that each of us chose to read. This was very much unplanned: we only decided to do it when we met up just before the event, but of course we all had our favourite bits marked in our copies and knew precisely what we’d like to read. What was so fun about this element was that it was different to a standard author reading, where – and I know I’m guilty of this – the author reads a bit they’ve probably read a dozen times, because they know it works, or it’s funny, or has got some sex in it. (And the humour, or comedy, of Ferrante is something that got discussed: Susanna said she remembered precisely the two points in the four books that made her laugh, and we agreed that while the books aren’t funny as such, and are full of violence, pain and misery, still there is something of the human comedy that runs through them; if their 1,600 pages were simply unremitting tragedy and trauma then we wouldn’t skip through as eagerly and easily as we – most of us – do.)

We read our passages in the order they came in the books, and introduced them by saying what the books and the author meant for us personally.

Susanna read from the second book, The Story of a New Name, from when the still teenage Elena has taken Lila along to her professor’s house for an evening of intellectual debate. Lila, the spikily intelligent but essentially unschooled best friend, says not a word all evening, while Elena tries valiantly to keep up and ingratiate herself, but once they’re out in the car, Lila sounds off to her husband, Stefano: Continue reading

A year in reading: 2014

I haven’t been keeping a strict list of books read during 2014 so this won’t be a strict list of best books, but rather a recollection of the most memorable reading experiences. Which itself leads to an interesting question. How much does a book have to stay with you after finishing it for it to be a good book? I ended my TLS review of Mary Costello’s remarkable Academy Street with the observation that I wasn’t sure if Tess was “the kind of character to stay with the reader long after the book is closed, but during the reading of it she is an extraordinary companion.”

I was discussing the book with David Hayden of Reaktion Books, and the name Deirdre Madden sprung up, whose latest novel Time Present and Time Past I’d just read. I said that I’d hugely enjoyed her earlier book Molly Fox’s Birthday, and that although that judgment stood – that it was a good book – I honestly wouldn’t have been able to tell you anything that happened in it at all.

What books have stayed with me, then? For new novels, Zoe Pilger’s helter-skelter semi-satire Eat My Heart Out and Emma Jane Unsworth’s more groundedly rambunctious Animals both offered up visions of contemporary Britain that I found winning and accurate, or appropriately overdone. Unsworth’s had the thing I thought Pilger’s lacked (though there was more at stake in Pilger) – a sense of where the character might be heading at the end of the dark trip of the narrative. Thinking back on Pilger’s book now, it occurs to me – and I wonder if it’s occurred to her– that Anne-Marie would make a superb recurring character. She’s great at showing where London is, a decade or so into the century. She’d be a useful guide to future moments, too.

The characters I spent the most time with over the year were Lila and Elena from Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels, aka My Brilliant Friend. I read the first volume early in the year, having been previously blown away by the gut punch/throat grab/face slap of The Days of Abandonment. I read the second and third Neapolitan volumes on holiday in the summer. I was reviewing it, so my proof copy is full of scribbles, but the scribble on the final page of Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay says just: ‘Wow’. As has been said before, these books do so many things – European political history, female friendship, anatomisation of Italian society, child to adult growth and adult to child memory – but it does two things that I found particularly powerful. Continue reading

Some thoughts on Elena Ferrante: the long and the short of it

Daniela Petracco of Europa Editions (standing) introduces, from left to right: Joanna Walsh, Catherine Taylor and myself. Photo courtesy Richard Skinner

Last night I was at Foxed Books in West London for the London launch for Elena Ferrante’s Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, the third in her ‘Neapolitan novels’ – a projected sequence of four books telling the intense, dialectical relationship between two women over, thus far, thirty years. What with Ferrante being a non-public author, it was up to others to do the promotional duties, and I was asked to join Joanna Walsh, who chaired, and Catherine Taylor to read from and discuss her work.

Walsh has written on Ferrante for the Guardian, while Taylor and I both reviewed the new book, she for The Telegraph and I for The Independent. It was a great evening, with what I hope was an interesting discussion, both for those that already knew Ferrante’s writing and those that didn’t, and some incisive comments from the floor.

As might be hoped, most of the talk was less about the enigmatic Ferrante herself, as about the books. As a critic, I have to say, it is a joy to be able to talk about the writer without the sense that they are listening in, and might stalk up to you at another launch, months hence, and throw a glass of wine in your face. (If it’s true, as the hints would have it, that Ferrante’s decision to absent herself from the public gaze is at least partly down to constitutional shyness, then I guess she doesn’t read her reviews.) Ferrante, so far as the critic is concerned, may as well be dead. Or, as the final two lines of one of her novels read:

Deeply moved, I murmured:

“I’m dead, but I’m fine.”

One theme that recurred over the evening, and that I think worth reiterating, is the highly specific Italian-ness of her books: the overwhelming, overweening importance of family; and, one circle further out from that, of ‘the neighbourhood’. These are facets of the Neapolitan novels that simply couldn’t be successfully transplanted to any other setting, not even really to, say Italian New York. And yet there is nothing foreign about them. The effect on the characters’ lives of ‘family’ and ‘neighbourhood’ in Ferrante’s books is at once universally recognisable and highly localised.

In preparation for the talk I read the two Ferrante books that I hadn’t read before (and, in fact, re-read another, The Days of Abandonment), and this drilled home for me one other aspect of her oeuvre, thus far, that is worth mentioning. Continue reading

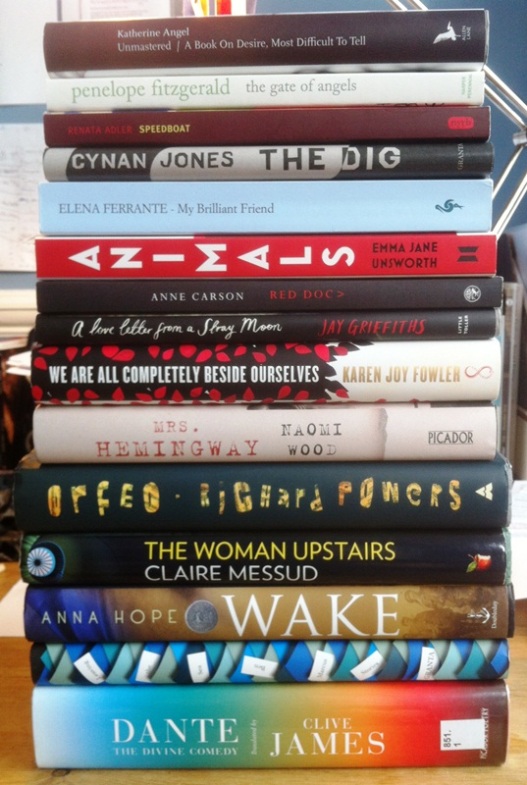

February and March Reading: Messud, Powers, Ferrante, Adler, Fitzgerald, Angel

I am bad. This is old. We are going back to early February here. I’ve been reading, but I’ve not got round to writing any of it up. There are two reasons for this, beyond sheer laziness. One of them is that I wanted to use one of these month’s round-ups to reconsider the whole ‘reading women writers’ / #ReadWomen2014 thing, which beyond being a prompt to myself to read more women was originally supposed to be a prompt to thought: not just why don’t I read more of them, but why do I read them as women; why when I’m reading them am I aware, at some level, of treating them, in my reading, as women writers, not male writers.

Is this true? Or do I just worry that it’s true?

Is awareness thought?

Am I turning into my own thought police?

Do I cut male writers more slack than women, or do I genuinely prefer male writers to women (my personal pantheon of contemporary writers, as I said before, starts with Geoff Dyer, Javier Marías, Knausgaard, Foster Wallace, Nicholson Baker… and goes through a few more, probably, before it hits Lorrie Moore, Lydia Davis.

And of course you’re entitled to question the very idea of the pantheon as a method of literary assessment.)

So, the four months I spent reading women last year was supposed to end with some kind of accounting of that experience, and it never did. I wanted to include that in my Feb reading post, but wasn’t ready to, hadn’t marshalled my thoughts.

I’m not ready now.

I have not marshalled my thoughts. Continue reading

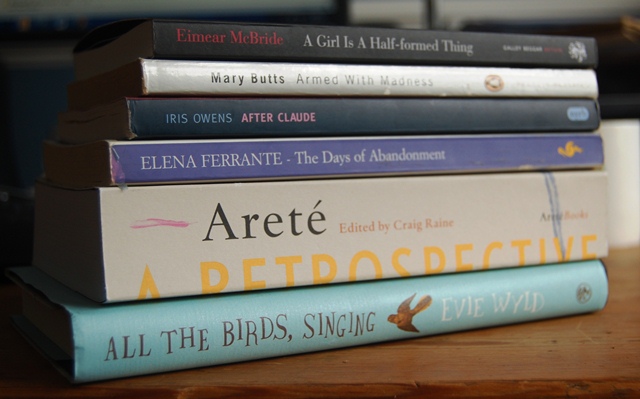

June and July Reading: Wyld, McBride, Ferrante, Owens, Butts, Arete

Two months’ reading conflated, due to the small matter of PhD thesis duly submitted, with this post rushed due to impending holiday – which, though, should allow plenty of time for more reading – and all coming out in the wrong order, a concatenation of events, stitched together with tiredness, a tinnitus of the calendar.

Two months’ reading conflated, due to the small matter of PhD thesis duly submitted, with this post rushed due to impending holiday – which, though, should allow plenty of time for more reading – and all coming out in the wrong order, a concatenation of events, stitched together with tiredness, a tinnitus of the calendar.

Working backwards, from July to June we have: After Claude, by Iris Owens, The Days of Abandonment, by Elena Ferrante, All The Birds, Singing, by Evie Wyld, A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing, by Eimear McBride and Armed With Madness, by Mary Butts. To which I’m adding a long poem, ‘You, Very Young in New York’, by Hannah Sullivan, from Areté’s Retrospective. Two new novels, one of them a new debut novel, the others recommendations from my Myopic/Misogynist reading list, one recent Italian translation and two classics of varying modernity – bitchy 70s New York, and and England between the wars.

And all touching, in one form or another, on madness, on a mind battling to contain and control the rising tide of reality – although strangely enough it’s the one with Madness in the title that least matches with what we think of as madness today – which I’d characterise as psychological disturbance. (I might be influenced in some of this by the fact that I’m married to a psychologist, who is very much against any kind of mystification or romanticisation of the topic.)

Perhaps that’s not surprising at all. Mary Butts’ book, Armed With Madness is a piece of modernism, coming somehow between Virginia Woolf and the Beats, if that’s a valid continuum, and seems to be of a time, or a moment, or a genre, that sees madness as something divine, and tragic, rather than, as today, something medical, and solvable. Continue reading