Tagged: Spring Journal

London Consequences 2 – a collaborative novel

Announcing a new and very exciting collaborative writing project: London Consequences 2.

London Consequences 2 is a collaborative novel being written from September to December 2022 by a collection of amazing contemporary writers (see below!). It is organised and curated by David Collard, Jonathan Gibbs and Michael Hughes, and is a creative response and homage to a little-known but very interesting book published 50 years ago called, yes, London Consequences.

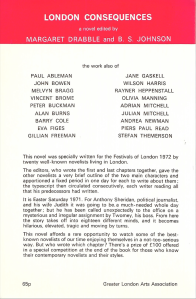

London Consequences was a collaborative novel written for the 1972 Festivals of Britain and edited by Margaret Drabble and BS Johnson. Drabble and Johnson co-wrote an opening chapter, and then passed the manuscript on to a series of 18 writers (including Melvyn Bragg, Olivia Manning and Eva Figes) who each wrote one chapter before passing it on, until it returned to the editors, who co-wrote the closing chapter. The published book listed the contributing novelists, but each chapter was anonymous, giving readers the fun parlour-game challenge of trying to work out who wrote what. (There was a £100 reward for whoever could successfully do this – as yet we have no idea if this was collected!)

Original writers:

Paul Ableman

John Bowen

Melvyn Bragg

Vincent Brome

Peter Buckman

Alan Burns

Barry Cole

Eva Figes

Gillian Freeman

Jane Gaskell

Wilson Harris

Rayner Heppenstall

Olivia Manning

Adrian Mitchell

Julian Mitchell

Andrea Newman

Piers Paul Read

Stefan Themerson

The original novel features a middle-class London couple, Anthony (a journalist) and his wife Judith (a mother and housewife) on a single day – Easter Sunday, 1971 – as they navigate the capital, and their relationship with each other. It was published in 1972 by the Greater London Arts Association, with a cover price of 65p.

The idea for this new project came about in a strange and serendipitous way. In April 2022 I turned 50, and Michael Hughes gave me as a present a copy of London Consequences, which I read and very much enjoyed. I tweeted that it would be a fun idea to do a contemporary version, to which David Collard, who knew the original, responded by throwing down the gauntlet. We should do it, he said.

Continue reading‘Spring Journal’ a year on: anniversary and review

On Friday 19th March 2021 it will be one calendar year since I lay on a sofa, phone in hand, and had the idle thought that one could tweet about the impending coronavirus pandemic, and the lockdown that had just started, in the form of a mash-up with / homage to / pastiche of Louis MacNeice’s ‘Autumn Journal’. I created a new account (that’s one of the things I love about Twitter as a creative platform; you can put ideas into action with no planning or forethought), grabbed my MacNeice Selected Poems paperback from the shelves, to copy those famous opening lines, and posted two tweets, that same evening. Here they are:

And here are the corresponding opening lines from MacNeice:

Close and slow, summer is ending in Hampshire,

Ebbing away down ramps of shaven lawn where close-clipped yew

Insulates the lives of retired generals and admirals

And the spyglasses hung in the hall and the prayer-books ready in the pew

And August going out to the tin trumpets of nasturtiums

And the sunflowers’ Salvation Army blare of brass

And the spinster sitting in a deck-chair picking up stitches

Not raising her eyes to the noise of the ’planes that pass

I carried on Tweeting my version of MacNeice in sporadic bursts over the next few weeks (I particularly remember standing in the aisle at Sainsbury’s Tweeting about standing Tweeting in the aisle at Sainsbury’s) and maybe the whole thing would have fizzled out if David Collard hadn’t asked if would like to feature the poem on his online salon A Leap in the Dark, which ran on Friday and Saturday evenings right through lockdown, on Zoom. It was a typically generous offer, but David’s stroke of brilliance was to invite, or persuade, Northern Irish novelist and actor Michael Hughes to do the readings – a canto a week, starting in early April, and running through until I had matched MacNeice’s 24 cantos. Michael read the final canto as part of a full read-through of my poem on Friday 28th August.

As it happens, the anniversary of the poem’s inception coincides with the first review of the book of the poem, which was published by CB Editions in December, after a typically nimble quick turnaround by Charles Boyle.

Tristram Fane Saunders in the Times Literary Supplement starts by setting the poem against the responses from more famous names (Don Paterson, Paul Muldoon, Glyn Maxwell), and is generous in his estimation of how my poem measures up to its inspiration and model:

aiming somewhere halfway between cheap pastiche and serious homage, Gibbs hits his mark. He nails Autumn Journal’s casual, yawning metres and late-to-the-party rhymes, its balance of didacticism and doubt.

You can read the whole review here.

(And if you have the print copy of the paper, you can have the additional thrill of turning the page to find, recto to my review’s verso, a review by Michael Hughes himself, of Anatomy of a Killing, by Ian Cobain.)

This anniversary also coincides with the vigil for Sarah Everard and protest against male violence on Clapham Common, so appallingly handled by the Met Police, which I mention only to point out the obvious fact that the pandemic only brought to the surface frustrations and inequalities that had been brewing and burning for much longer. And that if it felt like the six months during which I wrote the poem happened to have given me material to bounce at MacNeice, as it were, as a sounding board, then that’s missing the point. Whenever this had happened, these things or something like them would have happened, because they’re always happening.

The lines that Charles Boyle chose to put on the back of his edition of ‘Spring Journal’ were these:

Too many are dead, but jobs are dying too, all over.

The virus reveals the flaw

In our way of living: the rich fly it around the planet

And dump it on the doorsteps of the poor.

And the fact that the murder of Sarah Everard, and the way it triggered deep-lying anger about structural misogyny in our society, seems to repeat what happened last year when the murder of George Floyd did the same for structural racism, only goes to show that we are stuck in a cycle. The anniversary puts us no further forward in the kind of world we want to live in, and nothing to show for the lesson of so many dead.

As I wrote in August, in the penultimate canto of my poem, addressing MacNeice:

And then autumn will come,

And I’ll pass back the baton,

Let you handle your natural season,

And I’ll be there waiting, in March, when you’re done.

For as long as there’s something vicious looming

Beyond the horizon, and just as long

As we keep on getting things hopelessly wrong,

We can keep this thing turning, from poem to poem.

‘Spring Journal’

On the evening of Thursday 19th March 2020 I was lying on the sofa, phone in hand, when I had the idea of tweeting about the coronavirus epidemic in short poetic bursts, inspired by Louis MacNeice’s wonderful long poem ‘Autumn Journal’. I have used Autumn Journal in teaching poetry to undergraduate students, offering it as an example of how to write outwards from the self, how to mix politics and the personal to give a sense of how you see the world. I could do that, I thought. I could do it on Twitter.

I created a new account, @SpringJournal, and wrote two tweets that evening, and six more the following day. Each tweet contained four lines of poetry in MacNeice’s “elastic kind of quatrain”, with rhymes coming on alternate lines, but the line lengths immensely variable, while still keeping to a sort of rhythm. As well as his easy, down-to-earth way of tackling his themes, one of the other things I love about MacNeice is his rhyming. He allows for awkwardness in his syntax, he can be occasionally leaden, but he uses rhyme to pay things off, like a bell till chiming to mark the end of a transaction.

I’ve written more about the poem – and am posting Cantos as they are completed and edited – on a page on this blog, here.

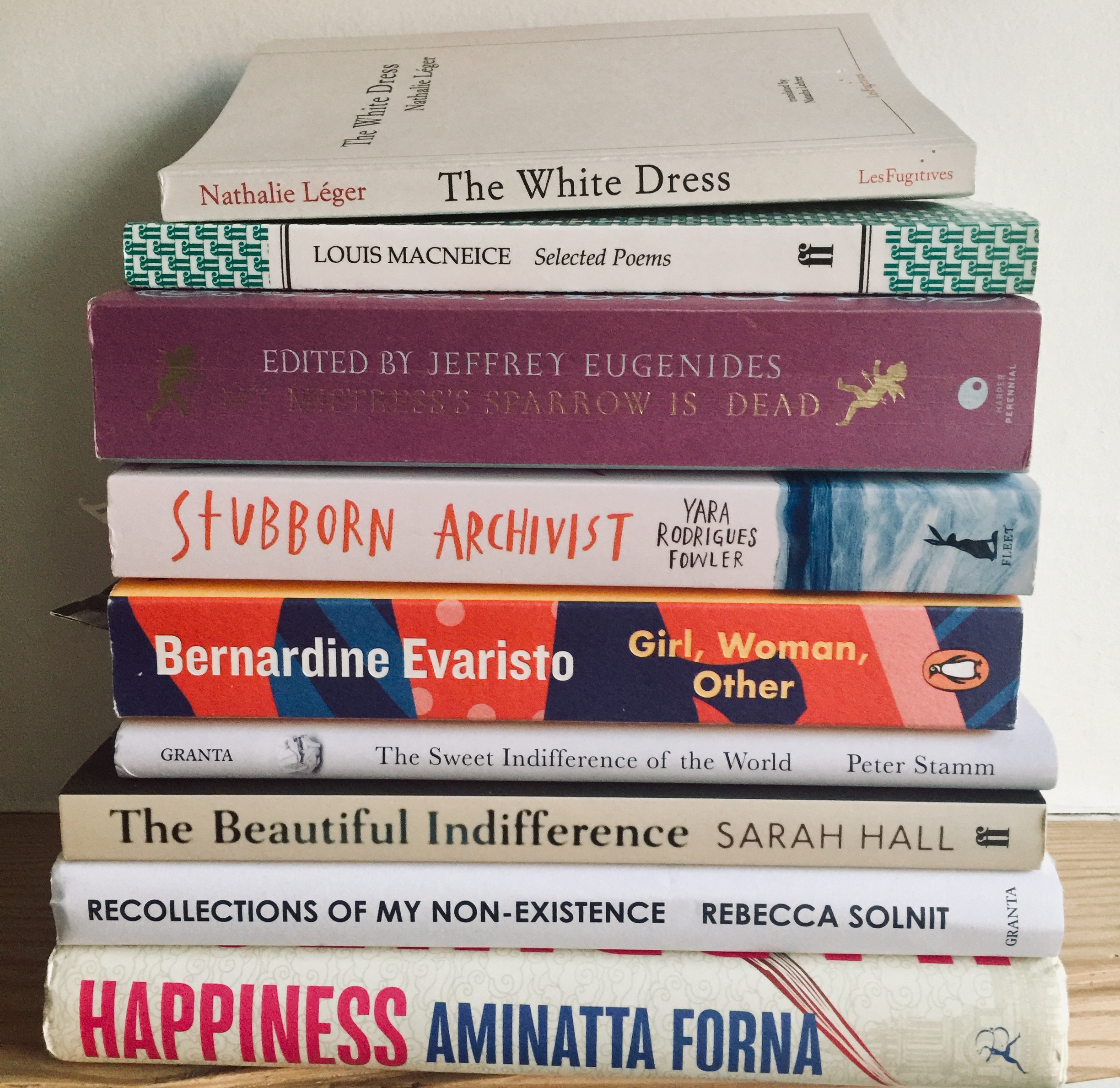

March Reading 2020: Stamm, Hall, Solnit, Léger, MacNeice

I have this problem with the novels of Peter Stamm. I love reading them, but they evaporate from my reading brain after I have read them – like the conceptual artist mentioned in Nathalie Léger’s The White Dress who pushed a block of ice around Mexico City until it melted entirely away. All that is left from my reading of All Days Are Night is a sense of a couple coming together in a ski resort, and an all-night rave of some kind, and of the relationship not working; Seven Years I remember barely at all; To the Back of Beyond is more memorable, perhaps because more high-concept: it is a novel built on an audacious idea that all the same builds that idea into something subtle, and moving.

The only thing I could remember about Stamm’s latest novel, The Sweet Indifference of the World, when I put it in that stack of books read in March, and photographed it with my phone, was the idea of the doppelgänger – which is also foundational to To the Back of Beyond. Beyond that, I could remember not a thing.

Writing this, though, the book has come back to me. It is just as audacious as To the Back of Beyond, and for that reason cannot be described. Let me repeat that Stamm tends to write books that start from an audacious conceit, but which drift away from it, or sink down into it, or in any case hedge or fudge their treatment of that conceit, so that you are never forced to actually judge it in the clear light of day, as you would with a piece of speculative or fantastical fiction that leads you to ask: yes, well, but would it actually work like that?

There is a kind of disintegration loops approach to the writing here – these are thought experiments that are allowed to unfold only so far until they start to disintegrate, while continuing to unfold.

Or: they are Schrodinger’s Boxes novels, that allow their conceits to both be and not be, and honour both in the telling, on the page, where normally things just are.

I’ve just picked the book up and flicked through it: no notes, no underlinings, which is unusual for me. And as I flicked through the book I thought about the nasty trick it plays with its gimmick; and that that’s precisely the reason for having it. It’s a book that undermines its own narrative strategy, or at least its narrator, that kills him off and leaves him alive to see it. It made me think of Simon Kinch’s excellent Two Sketches of Disjointed Happiness, which plays a more similar trick, I think, to To the Back of Beyond. There is something to be written about doppelgängers in fiction – not the simplistic Jekyll and Hyde type, but the type of novel that plays with the foundational idea of narrative that the narrator is a stable, indivisible unit. There’s also Geoff Dyer’s The Search. It is only men who write this kind of novel?

A thought experiment novel, I like that. Perhaps also a little like a Borgesian novel, if Borges hadn’t been too lazy (to use his word) to write one, and had had the patience to let his conceit roll out and gradually disintegrate, like the 1:1 scale map in That Empire in ‘On Exactitude in Science’.

Just for reasons of titular symmetry I’ll move from Stamm to Sarah Hall’s The Beautiful Indifference. Now, I’ve never quite managed to get to grips with Hall as a writer: I’ve failed to make significant headway with any of the novels of hers I’ve tried, and although I remember being quite affected by the story ‘She Murdered Mortal He’ – the part with the creature following the woman along a beach in some far off holiday country – and I’m sure that I did get to the end of the story at least once, I was still surprised by that ending when I read it this time.

This time I read it because Hall was again picked as part of a Personal Anthology. Continue reading