Tagged: Don DeLillo

January Reading 2021: DeLillo, Moore, Townsend Warner, Power, Oyeyemi, Rooney, Fuller

This post is built out of my year-long reading thread on Twitter, but expanded.

I started the year with a short Don DeLillo blitz, research for an academic chapter I’m writing. Some of this was rereading, but Americana, his 1971 debut, was one I hadn’t read before. It is strangely split into different parts, as if moving through different tonal landscapes, which is not an approach I associate with this writer.

The opening is a zippy corporate media satire – at times like Joseph Heller’s Something Happened, published three years later – with lots of cynical male advertising executives trying to screw each other over, and screw each other’s secretaries. It then diverts into a long dull suburban childhood flashback, and then goes on a Pynchonesque road trip across the country, fantasmagorical in parts, skippably dull in others.

My conclusion on Twitter was: In the end I suppose I’m just not in the market for these old myths – which, now that I think about it, is basically a paraphrase of the opening line of Apollinaire’s Zone: “À la fin tu es las de ce monde ancien.” Unlike for Pynchon’s freewheeling carnival of invention, I got the feeling I was supposed to care for these characters, in their struggle to care about themselves, and there were simply too many unexamined assumptions that don’t align with my own for that to apply. It tries too hard to be cool, to shock, to provoke; it flails around to distract you from the fact it doesn’t know what it wants to mean, but as a debut novel it’s still hugely impressive and quite powerful.

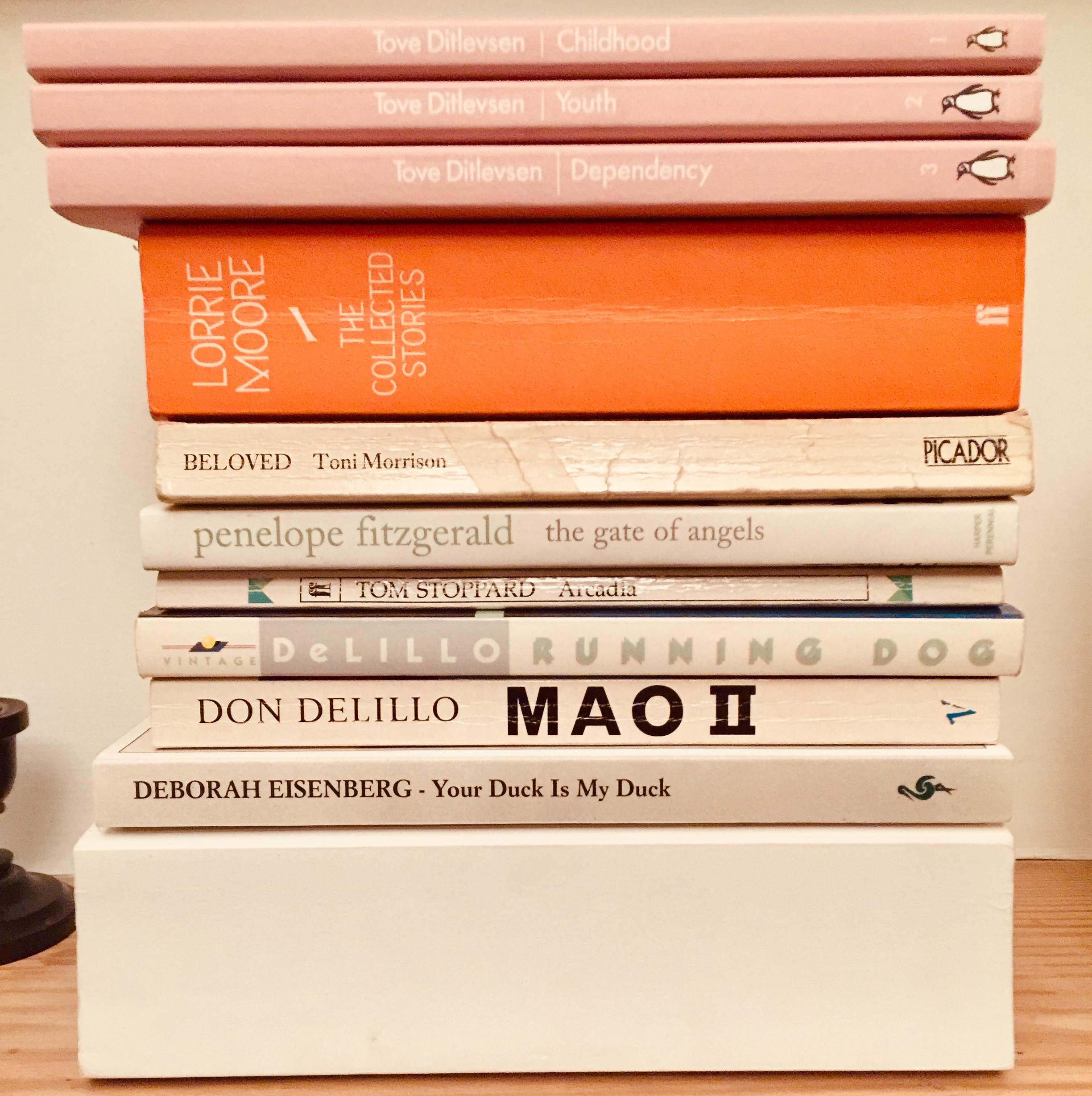

I also zoomed through Great Jones Street (1973) and Running Dog (1978). In all these books DeLillo seems to be pushing against the novel form, wanting to find some other way of getting through than via a standard plot arc. Great Jones Street is interesting because of what it says about celebrity, and about music – which is a subject DeLillo has never really returned to. Running Dog to an extent is interesting about the mystique that arises when art and money converge, but he mishandles the thriller plot he starts off by gleefully satirising. The ultra-hardboiled dialogue boils dry, with pages and pages of interchangeable spooks tough-talking each other in the backs of limousines. There is an impressively destructive ending – as destructive as Great Jones Street, but really you get the sense that he’s given up before we even get there. By ‘given up’, I mean given up trying to find a way to resolve the plot in a way that honours equally his characters, his themes, and any remaining sense of reality/realism/credibility.

More on novel endings later in this post.

After DeLillo I moved onto A Gate at the Stairs by Lorrie Moore, which I’ve tried to read at least once before, but didn’t get far into. As with Moore’s best stories it made me absolutely snort with laughter on a regular basis. It also ends wonderfully and movingly and, in a way, thrillingly – doing that thing that I think DeLillo has tried to do, to move outside or above the confines or sphere of novelistic plot: not just giving you what you think deserve from what has come before.

It’s clever in the way it stretches what could have been a fine long short story to over 300pp, but there’s too much stodge: more childhood flashback than is necessary (with Americana, is this a lesson?), even bearing in mind the emotional ballast it contributes to the payoff at the end, and too much compulsive-idiosyncratic detail, delivered by the bucketload. This last is of course a familiar aspect of Moore’s short stories, and perhaps she simply though that the same intensity of narratorial gaze can be endlessly extended without consequence, but it ain’t so.

Lorrie Moore’s short stories work because we can only bear to spend so much time with her characters.

To which her characters would doubtless say, Imagine what it’s like being us!

To which I’d say, That’s not how this works.

Continue readingAugust Reading: DeLillo, Ditlevsen, Eisenberg, Ellmann, Moore, Morrison, Proust

(What a pleasingly alliterative set of author names)

(What a pleasingly alliterative set of author names)

There’s an epigraph that I often remember, from Dave Eggers’ debut A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius (2000 – and boy I wonder if anyone’s read or reread that book recently. It would be an interesting experience.) In fact the book has two memorable epigraphs: firstly, ‘THIS WAS UNCALLED FOR.’; and, secondly:

First of all:

I am tired.

I am true of heart.

And also:

You are tired.

You are true of heart.

Both of them sum up the radical sincerity and potential mawkishness at the heart of his writing. Both, because of this, are memorable. They stay with me, because as statements they are so widely applicable – they are applicable now – as well as being pertinent to the book for which they act as curtain raisers, or perhaps, rather, mottos painted on the safety curtain of the book’s theatre.

I am tired. Teaching starts next week. Summer’s over. I am sure that you are tired. I make no claims for the trueness of either of our hearts, but let’s accentuate the positive.

I am tired. That’s it. That’s the tweet.

And but so:

Books are wonderful relaxation. They are also wonderful energising. There’s nothing I love more than grabbing my phone to tweet a response to something I’m reading, whether it’s Don DeLillo describing a woman putting a condom on a man’s penis as “dainty-fingered and determined to be an expert, like a solemn child dressing a doll”,

No big deal, just a DeLillo sentence describing someone putting a condom on a penis. Fuck sake, Don. pic.twitter.com/i5oBTEN1ly

— Jonathan Gibbs (@Tiny_Camels) August 31, 2019

or Lorrie Moore pole-axing the reader with the devastating end to the first page of her story ‘Terrific Mother’.

Here is the first page of ‘Terrific Mother’. Who else would *dare* to open a story like that? pic.twitter.com/vr4qFHJFXR

— Jonathan Gibbs (@Tiny_Camels) August 22, 2019

I’ve been trying to read Proust with my phone to hand, too, as an enhanced form of annotation, and that, too, has been fun and exciting.

Fun and excitement: wow. That’s it. That’s the tweet.

But, sometimes, writing about books can be a chore. It’s a terrible thing that a book, once read, even a good book, can be put on one side and forgotten. What’s the point of all of this, you think, if a book that engages your brain and emotions over a number of hours over a number of days just gets put back on the shelf and, to all intents and purposes, forgotten? Because sometimes they are picked up again. Sometimes they are passed on. My August reading contained left-turns and blind alleys, slogs up stony hills and brief gleefully shrieking slides down sandy dunes. There was reading for work, reading for the soul, reading by accident and reading by design.

The Don DeLillos are there for an academic chapter I’m writing, and I found myself zooming through them. Mao II, a re-read, is far from my favourite of his novels: too slick and portentous, too glib in the way it throws around its themes.

In one aspect at least it’s a victim of its success. The famous riff about terrorists having replaced the novelists at the heart of the inner life of the culture is blandly prophetic, but it’s too on the nose. The other ‘prophetic’ moments or images in his novels – such as the most photographed barn in America, or the playing dead response to the Airborne Toxic Event, are more oblique, more generally symbolic. The writing is spiffing. It’s spiky poetry has just become too easy to read.

Running Dog, by contrast, I enjoyed. I don’t think I’d read it before. It’s more corny in its plotting – closer to a spy thriller or a contemporary hardboiled thriller – and that allows the author to have more fun, and for the punchier writing to stand out from the more familiar skeleton. Another extract I tweeted managed to pick out something that occurred to me elsewhere about the male (I think) approach to language. Here it is: Continue reading

Unspeakable behaviour, of the very best kind: Ten fictional artists

“Tell me this,” says a character in Don DeLillo’s novel, Falling Man: “What kind of painter is allowed to behave more unspeakably, figurative or abstract?”

It would be easy enough to rack up examples on both sides, from fiction, no less than from real life. Novelists love artists as characters, after all. If books furnish a room, then artists furnish a novel – with their artworks, and their antics. You might say they are the perfect writer’s avatar: analogue, clown and straw man rolled into one. Their created work is so much more describable than prose, their creative act too. And they get to have models, some of them, to go to bed with.

My novel, Randall, is, in intention, an satirical and elegiac alternative history of Young British Artists and art world in general, and while writing it I’ve naturally collected a menagerie of other fictional artists, sometimes badly behaved, sometimes not, but all exemplary in the way they dramatize an aspect of human nature that is, by definition, out there.

The Horse’s Mouth, by Joyce Carey Continue reading

February reading: Means, DeLillo, Hollis, Perrotta, Walser, Baker, Proust

Close reading is one of the joys of academia. You have to read stuff over and over again, you can’t give it the benefit of the doubt, and let it just slide by you. Thus a multiple reading, among the chaos of a weekend when I probably should have been doing something familial, of David Means’ story The Gulch.

Short stories have such obvious pleasures, and yet are – for me – such hedged around with confusion and uncertainty, that I positively love it when someone instructs or encourages me to read one. One – out of so many.

Short stories have such obvious pleasures, and yet are – for me – such hedged around with confusion and uncertainty, that I positively love it when someone instructs or encourages me to read one. One – out of so many.

Collections of short stories, it often seems to me, are quite the worst place to read short stories. The presence of so many others, equally good, a few pages to the left or the right, seem to make the piece you are reading embarrassingly contingent, at worst redundant, as if they’re somehow shrugging at their own existence.

It is the wonderful trick of the novel, the bossy, lazy, egotistical novel, to make you feel, as you are reading it, that it is somehow necessary, obvious, inescapable. That they are the only novel in your life. In between readings, if it’s a good one, the novel will percolate, stew, grow, run the laps of your synapses. It’s got stamina. It’s got the time and the space to include its own rereadings (repetitions). Stories, even those as good as The Gulch, demand rereadings – which is a risk: after all there are all those other stories right there waiting to be read.

The DeLillo jag (Point Omega, again, most of The Angel Esmerelda, Running Dog) was academia-related, too. Point Omega, on about the third reading, is increasingly brilliant. What I’m coming to admire most about DeLillo, once I get beyond the pacing and the dialogue (okay: the sentences – even the spaces between the words seem charged, the prose equivalent of the Pinter pause) is the insouciance with which he manages to bring tacky low-rent thrillerish elements into his ascetic, high-flown prose. In Point Omega he actually (okay: not actually at all) brings Norman Bates down off the screen in the plot of the novel. He’s got a serial killer in his book, for crying out loud. It shouldn’t work. It should be like having a clown tumble on stage in the middle of Swan Lake. But somehow he pulls it off. Continue reading

January reading: Jenkins, Roth, Bakker, Houellebecq, Iyer, Dyer, Burnside, Masters, Knausgaard

I started the month finishing Elizabeth Jenkins’ The Tortoise and The Hare, a mid-20th century novel reissued in chichi hardback (there’s becoming something of a glut of them, isn’t there?) by Virago, with an introduction by Hilary Mantel. It was a Christmas present, though quite why my wife chose to give me a book about the breakdown of a marriage, I’m not sure.

The novel is one of those (like Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday) that is entirely governed by the formal gesture of its narrative: in this case, the gradual and implacable usurpation of the wifely role to rich, shallow barrister Evelyn Gresham by ‘handsome’, practical Blanche Silcox – to which Evelyn’s floaty, feminine wife, Imogen, can only stand by and watch. Any deviation from this movement (the possibility of Imogen having an affair, the needs and desires of the Greshams’ horrid son Gavin) gets dragged into the slipstream of the narrative and ruthlessly flung aside.

The novel is one of those (like Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday) that is entirely governed by the formal gesture of its narrative: in this case, the gradual and implacable usurpation of the wifely role to rich, shallow barrister Evelyn Gresham by ‘handsome’, practical Blanche Silcox – to which Evelyn’s floaty, feminine wife, Imogen, can only stand by and watch. Any deviation from this movement (the possibility of Imogen having an affair, the needs and desires of the Greshams’ horrid son Gavin) gets dragged into the slipstream of the narrative and ruthlessly flung aside.

The key moment of the book comes for the reader when they realise that there is nothing organic about the plot’s progress: it is entirely teleologically determined. Jenkins knows exactly where her characters are going to end up: Blanche in Imogen’s place, Imogen cast out. It’s as mathematical as a Pinter short, or Ionesco’s The Lesson. There is something unreal about the bluntness of this reversal, though it’s mitigated by the domestic texture of the prose. (That said, the book does commit a venal sin: “books that include minor characters just to satirise them”)

Here is Karl O Knausgaard on form: “Form, which is of course a prerequisite for literature. That is its sole law: everything has to submit to form. If any of literature’s other elements are stronger than form, such as style, plot, them, if any of these take control over form, the result is poor. That is why writers with a strong style often write poor books. That is also why writers with strong themes so often write poor books. Strong themes and styles have to be broken down before literature can come into being. It is this breaking down that is called ‘writing’.” (From ‘A Death in the Family’ – more on this below.) Continue reading