Tagged: WG Sebald

A first look at Patrick Modiano: ‘The Search Warrant’

Yesterday I picked up, in the UEA library, the English translation of Nobel laureate Patrick Modiano’s non-fiction book Dora Bruder (translated by Joanna Kilmartin for Harvill as The Search Warrant) and read it on the train back to London – easy enough to finish in the two hours that journey allots.

Yesterday I picked up, in the UEA library, the English translation of Nobel laureate Patrick Modiano’s non-fiction book Dora Bruder (translated by Joanna Kilmartin for Harvill as The Search Warrant) and read it on the train back to London – easy enough to finish in the two hours that journey allots.

And, despite its subject matter, it is an easy read: clear without being limpid, articulate without eloquence, conscientious and free of guile. It is easy to see why a book such as this might appeal to the Nobel committee. It sets writing out as a humane art, a way of seeing clearly, with none of the complications and doubts that Twentieth Century thought has thrown up to complicate and explain our inability to come to terms with our own history.

That’s not to say that there is no ambiguity in Modiano’s book, which is his account of his attempt, over many years, to uncover what traces remain of a Parisian Jewish teenager sent to the camps, starting from a short notice in a newspaper, in 1941, asking for her whereabouts after she had run away from her convent school.

(It’s tempting to talk about Modiano’s writing, but I can’t yet generalise about that; this is the first book of his I’ve read. I’ve just started an earlier novel, with another, in French to follow. For a useful overview, see Leo Robson’s piece for the New Statesman.)

So, yes, the book is full of gaps, but the gaps are seen clearly. The author is present, inserting elements of his own autobiography as well as the details of his search of Dora, but his presence is a stable one, troubled but untroubling. There is none of the anguished breast-beating of Laurent Binet’s HHhH, in which the author questions his motives in writing about the activities of the Third Reich, and even his right to do so. There is none of the strategic obfuscation of WG Sebald, whose path through the labyrinth seems to build new, secondary or side-labyrinths, splitting off like fractals, as he goes. Continue reading

December reading: Mann, Arendt, Bataille, Chandler, and Ken Worpole and Jason Orton

You know those people who reread Ulysses every year? I hate those people. Those with long memories may remember that the book I was reading as 2013 began was Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain.

Well, I can now reveal that the book I’m reading as the new year turns is… again, The Magic Mountain. Or, rather, still The Magic Mountain.

This wasn’t a reread, oh no. This was the same, first read. I just hadn’t finished it yet. Other books had been read in the meantime, of course, and for most of the year I wasn’t reading it at all. But I picked it back up, in November, turned back 50 or so pages, and pressed on.

It’s a slow, hard read, this book, a slow, hard climb. But the views, when you pause and turn and take stock, are jaw-dropping, the flora underfoot often charming, and the intellectual air bracing to say the least.

Set in the years before the First World War, Mann’s novel opens with young, healthy (in body and mind) engineer Hans Castorp visiting his soldier cousin Joachim in a Swiss sanatorium, where the latter is being treated for tuberculosis. The three week visit turns into a temporary and then indefinite stay when he develops first a temperature, and then is found to have “a moist spot” in his chest.

The narration of these three weeks, I feel it must be said – and the author feels it needs pointing out too – takes up over 200 pages, during which there is a lot of talk, a lot of ideas tossed artfully around, much of which is intriguing enough when it occurs, but little of which I could safely summarise for you now. Does this matter? I’m not sure that it does. There has been no point in this book at which I have not wanted to read on; as Mann puts it in his foreword, “only thoroughness can be truly entertaining.”

Foremost among the brilliancies of the book is that Mann is especially alert to the fact and activity of reading; he is constantly concerned with how the novel will appear from the far side of the textual abyss. In the foreword he warns that the story is going to take more than a moment or two to tell. “The seven days in one week will not suffice, nor will seven months […] For God’s sake, surely it cannot be as long as seven years!”

After those three weeks, easily demarcated in the text, time starts to act weirdly, and how long the events of the rest of the narrative are supposed take is never quite clear. Which in fact makes it perfect for this kind of uncertain and extended reading that I have been giving it: reading, in fact, that becomes as cyclical and seasonal as Hans Castorp’s stay in the sanatorium. Up there in the Swiss Alps, in that strange pre-war time (when Weimar Berlin, for instance, was being highly temporally specific) time expands and contracts; it exists in a very different to way to the time in Proust. There, the past is something gone, that must be sought out to be retrieved. Here, the past is never truly past, it floods up and engulfs the present. Time (and illness) is something to be escaped, not found again. Continue reading

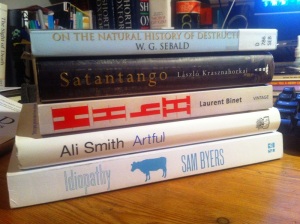

November reading: Krasznahorkai, Binet, Byers

Reading Lászlo Krasznahorkai’s Satantango was a struggle. I wish it hadn’t been, and I’m the first to argue for the improving qualities of difficult books, but this was one that I persevered with in the face of a dwindling conviction that I was going to be able to make any sense of it.

I picked it up largely out of respect for the names on the cover and title page – admiring quotes from WG Sebald (who has loomed large in my reading this year) and Susan Sontag, and the added interest of reading the translation of George Szirtes, lest we forget he is significantly more substantial a literary presence than his marvellous Twitter feed.

I knew nothing about the author, nothing about the book, and took the opportunity to add nothing to this sum before reading – as someone pointed out about the Olympic opening ceremony, the opportunity to sit down to a cultural experience with absolutely no preconceptions is a rare one. Nor have I read anything about the book since finishing it, which I am tempted to do now, in part to see what it is I missed. For a lot of its incredibly dense 270 pages I was trying, trying so hard, to find meaning, discern allegory, pick out the thread or symbol or standpoint that would allow me to take a view on the book as a whole.

I knew nothing about the author, nothing about the book, and took the opportunity to add nothing to this sum before reading – as someone pointed out about the Olympic opening ceremony, the opportunity to sit down to a cultural experience with absolutely no preconceptions is a rare one. Nor have I read anything about the book since finishing it, which I am tempted to do now, in part to see what it is I missed. For a lot of its incredibly dense 270 pages I was trying, trying so hard, to find meaning, discern allegory, pick out the thread or symbol or standpoint that would allow me to take a view on the book as a whole.

Forgive the clumsy phrasing, but never has there been a book so impossible to read between the lines of. Continue reading

July reading: Blackburn, Ridgway

Some months go by and you look at the list of books you’ve read and wonder: how so short? How can I have read so little? The reasons are often dull, though sometimes they do come down to a lack of engagement with the books to hand, sometimes a lack of engagement with the idea itself of reading, or perhaps the idea of reading novels.

After finishing Keith Ridgway’s Hawthorn & Child (which I’ll get to below) I picked up and put down Christoph Simon’s Zbinden’s Progress (didn’t grab me at all), Richard Beard’s Lazarus is Dead (oh, I thought, after reading less than two pages, it’s Joseph Heller’s God Knows) and Thierry Jonquet’s Tarantula (as recommended by a detective in Houellebecq’s The Map and the Territory… but, my god, the translation is appalling, and the “story of obsession and desire, or power and revenge” more or less the level of any other Sade knock-off). Perhaps I’m jaded. Perhaps I’m read out. Perhaps I’m waiting for August, and the chance to leave London and sit outside a tent or by a pool and really get into a ‘big’, ‘proper’ novel. Continue reading

After finishing Keith Ridgway’s Hawthorn & Child (which I’ll get to below) I picked up and put down Christoph Simon’s Zbinden’s Progress (didn’t grab me at all), Richard Beard’s Lazarus is Dead (oh, I thought, after reading less than two pages, it’s Joseph Heller’s God Knows) and Thierry Jonquet’s Tarantula (as recommended by a detective in Houellebecq’s The Map and the Territory… but, my god, the translation is appalling, and the “story of obsession and desire, or power and revenge” more or less the level of any other Sade knock-off). Perhaps I’m jaded. Perhaps I’m read out. Perhaps I’m waiting for August, and the chance to leave London and sit outside a tent or by a pool and really get into a ‘big’, ‘proper’ novel. Continue reading

June Reading: Sebald, Clark, Joseph, Barthelme, Ridgway, Moore, Updike

This month I finished reading two books that had been lying open – by my bedside, on my desk – for months and months: WG Sebald’s Rings of Saturn (a re-read) and TJ Clark’s The Sight of Death. Obviously, this makes them the opposite of page-turners – page-turn-backers, perhaps, as, with the Sebald especially, I found myself going back and starting chapters over, settling myself back in to whichever slippery, slow-moving digression he was taking me on. With the Clark the stop-start process was not a problem. I knew what I was reading it for: I was reading it for insight, for ideas about how we look at paintings, and what it means to come back and look at paintings over and over again, day after day, rather than assume that we can take them in at one glance.

It’s a marvellous book about art, that exhibits its authority not in the range of its reference (though that’s there), but in the focus of its attention. In it Clark spends a six-month sabbatical sitting in a gallery looking at two paintings by Poussin, giving his thoughts not in a clever post-hoc essay, but in diary form, as they come. It makes me want to read Martin Gayford’s Man With a Blue Scarf, his book about sitting for a portrait by Lucien Freud, which presumably has as much to say about the day-to-day process of art on the other side of the aesthetic divide.

Clark’s book might have something to say about why I’ve chosen, or ended up, reading the Sebald in slow, overlapping, self-replicating waves, rather than a simple linear progression. He is particularly good on the importance of the viewing position in front of the painting, something that is impossible to recreate with any kind of reproduction – and boy the reproductions in The Sight of Death are good, dozens and dozens of details on high-gloss paper, magnified crops to illustrate whatever point Clark is making. I went to see one of ‘his’ Poussins in the National Gallery last week, and it was – in its current condition, or lighting, or situation – a sad and muddy mess: impossible to make out even half of what the book shows us, but then Clark is all about the contingencies of the moment: the hanging, the room in the gallery, whether the lights are on or off, the weather outside. He says:

So pictures create viewing positions – don’t we know that already? Yes, roughly we do; but we have only crude and schematic accounts of how they create them, and even cruder discussions of their effects – that is, of how the positions and distances are or are not modes of seeing, modes of understanding, intertwined with the events and objects they apply to.

Every time he goes back to look at the painting he must reorient himself in front of it, let himself work his way back in. Does something similar happen with books? Perhaps. The key problem with Sebald, for me, is how you should negotiate the information he gives you. Continue reading

March reading: The seduction styles of Gale, Le Carre, Sebald

March has been a strange month for reading. It looks like not a lot got read, but there was plenty of Adorno and Benjamin and DeLillo, mostly in bits and pieces, that’s just not going to get a look-in on this blog. From last month I’m glad to say I finished Nicholson Baker’s Room Temperature – a slim, wondrous book, that I was thrilled to be able to pass on to my brother-in-law, who’s about to enter that strange second world of parenthood – and I was equally thrilled to read Just William’s Luck’s review of Chris Bachelder’s Abbott Awaits, which I’ll be looking out when I’m in the US next month. Together these two books make up what must be the totality of that minor sub-genre Intelligent Dad-Lit. Any other contenders, let me know.

Reviewing-wise, I read Tom Perrotta’s The Leftovers (for the TLS) and Patrick Gale’s A Perfectly Good Man (for the Indy). A sobering pair of authors for someone just having had his own novel sent out to publishers, and seeing the first rejections come back. Here, you might think, is how to write bankable books. Gale’s characters, especially, are delivered up on a plate – so touchable, so knowable, it’s almost fetishistic. People should stop going on about Franzen and McEwan – Gale is today’s realist novelist par excellence, if you take realism to be the strand of literature that sets out, above all, to flatter the bourgeois readership that they, too, have, if not immortal souls, then inviolable selves. Good god, you think: if these characters on the page seem real, then how much more real must I be! (The comeback, of course, being that you only feel real, dear reader, because you’ve been hypnotised into it by all those novels you’ve read.) Continue reading

Reviewing-wise, I read Tom Perrotta’s The Leftovers (for the TLS) and Patrick Gale’s A Perfectly Good Man (for the Indy). A sobering pair of authors for someone just having had his own novel sent out to publishers, and seeing the first rejections come back. Here, you might think, is how to write bankable books. Gale’s characters, especially, are delivered up on a plate – so touchable, so knowable, it’s almost fetishistic. People should stop going on about Franzen and McEwan – Gale is today’s realist novelist par excellence, if you take realism to be the strand of literature that sets out, above all, to flatter the bourgeois readership that they, too, have, if not immortal souls, then inviolable selves. Good god, you think: if these characters on the page seem real, then how much more real must I be! (The comeback, of course, being that you only feel real, dear reader, because you’ve been hypnotised into it by all those novels you’ve read.) Continue reading