Category: Yearly reading

Books of the Year 2023

As for the last few years, I’m reading fewer new books, in part as my university teaching replaces book reviewing as the driver of much of my ‘strategic’ reading, and in part perhaps because of my continued and always-belated attempted to catch up with unread classics (2023: War and Peace; 2022: Moby-Dick, Ulysses, Anna Karenina; 2019-20: In Search of Lost Time; Middlemarch; 2024? I’m not sure yet…)

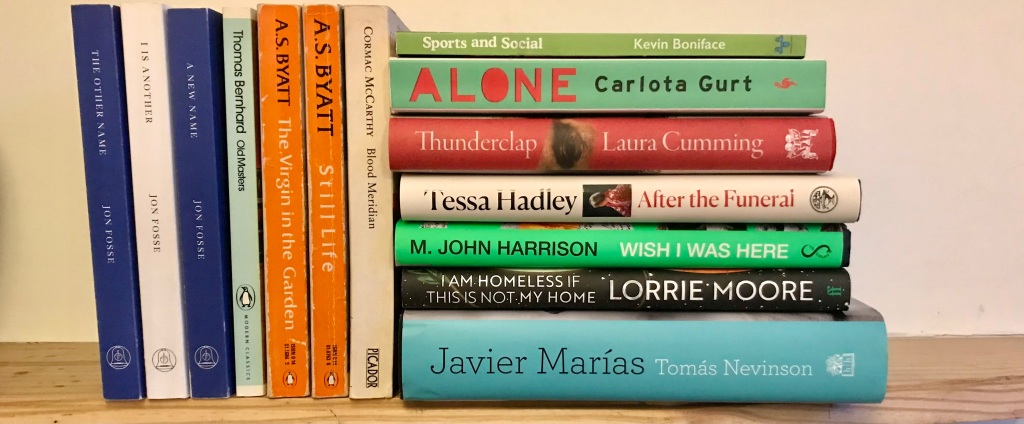

Anyway, here are my ‘books of the year’ – I’m keeping the title for consistency’s sake, though really this is intended as a record of my reading. In 2023, as I’ve done in some of my previous years, I kept a ‘reading thread’, which migrated halfway through the year from Twitter/X to Bluesky. (I’m keeping my X account live, really just for the purposes of promoting A Personal Anthology; I’ve deleted it from my phone, and carry on my book conversations now on Bluesky). I’m grouped the books according to i) new books, i.e. published in 2023 ii) books read by authors who died in 2023 iii) other books, with a full list at the end.

Best new books

After the Funeral by Tessa Hadley was my book of the year. She is truly a contemporary master of the short story. I delight in her rich use of language, in her ability to draw me into characters’ lives and particular perspectives (though I’m aware that, in broad sociological terms, those characters are very much like me) and in the power and deftness with which she manipulates the narrative possibilities of the short story. She’s like an osteopath, who starts off gently – you think you’re getting a massage; you feel good; you feel in good hands – but then she does something more dramatic, leaning in and applying leverage, and you feel something shift, that you didn’t know was there. ‘After the Funeral’ and ‘Funny Little Snake’ are both brilliant stories well deserving of their publication in The New Yorker. ‘Coda’ is something else: it feels more personal (though I’ve got no proof that it is), more like a piece of memoir disguised as fiction, which is not really a mode I associated with Hadley. I read or reread all her previous collections in preparation for a review of this, her fifth, for a review in the TLS, and I have to say: there would be no more pleasurable job that editing her Selected Stories – the collections all have some absolute bangers in them – though equally I’d be fascinated to see which ones she herself would pick.

Tomás Nevinson by Javier Marías, translated by Margaret Jull Costa. Not a top-notch Marías, but a solid one: Nevinson is a classic Marías sort-of-spook charged with tracking down and identifying a woman in a small Spanish town who might be a sleeper terrorist, from three possible targets, which naturally involves getting close to and even sleeping with them. I found some of the prose grating – flabbergastingly so for this writer (“we immediately began snogging and touching each other up” – I mean, come on!) – but the precision of the novel’s ethical architecture is absolutely characteristic.

Alone by Carlota Gurt, translated by Adrian Nathan West. A compelling and moving Catalunyan novel about the stupidity of thinking you can sort your life out by relocating to the country. Similar in theme to another book I read this year (Mattieu Simard’s The Country Will Bring Us No Peace) though I liked that one far less. I won’t say much about it as I read it without preconceptions and recommend it on the same terms. I will say it reminded me of The Detour by Gerbrand Bakker, which is another novel of solitude and the land, which again benefits from stepping into as into an unknown locality.

I am Homeless if This is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore. Oh boy. I love love love Moore at her best and though this aggravated as much as delighted me it’s been nagging me ever since I really want to go back and read again. [NB I have gone back to it, as my first book of 2024, and am being far less aggravated than on the first read). After a brisk, unexpected and exhilarating opening the novel seems to go into stasis, a slow series of disintegrating loops. It fails to do the thing that Moore usually seems to do quite effortlessly: keep you dizzily engaged with a cavalcade of daft gags and darkly sly sharper wit and observation. The protagonist, Finn, seems to miss what Moore usually gives her central characters: a dopey friend to dopily muddle through life with. He has a brother, Max, but he’s dying, and an ex, Lily, who, well… But all of this is done in flat dialogue wrestling with the big questions. Moore usually lets the big questions bubble up from under the tawdry minutiae of life (as, brilliantly, in A Gate at the Stairs); here, they’re front and centre. More tawdry minutiae, I say! I think part of my frustration with the novel comes from a place of ‘Creative Writing pedagogy’. Wouldn’t it be better, I think, to open up Finn’s character, show him as a teacher, his banter with the students, and his entanglement with the head’s wife? Rather than making all of that backstory, dumping it into reflection. The scene with Sigrid, for instance – her attempts to flirt with Finn – would be stronger if we’d already met her in the novel, already seen their relationship (such as it is) in action. You tell students, first you establish the ‘normal’ of the protagonist’s existence, then you throw it into confusion. So, am I giving LOORIE MOORE MA-level feedback? Well, yes. To which the response (beyond: “she’s LORRIE MOORE”) is: she’s not writing that kind of ‘normal’ novel. For every bit of LM brilliance (the gravestone reading “WELL, THAT WAS WEIRD”; the line “Death had improved her French”) there’s something off, that should or could be fixed or cut: the cat basket sliding around on the car backseat; the scene where Finn’s car spins off the road.

A Thread of Violence by Mark O’Connell. A suavely written book that digs into the true crime genre but stops short of the moral reckoning it at least flirts with: that in truth it shouldn’t exist – as a published book, at least. Will surely sit on reading lists of creative non-fiction in the future.

Tremor by Teju Cole. Read quickly and carefully (in physical not mental terms: it was bought as a Christmas present and sneakily read before being wrapped up and given ‘as new’), with the full intention of going back and reading it again. Cole is a literary intelligence for our times, that I’d drop into the Venn diagram of the contested term ‘autofiction’, not for its supposed relationship to the author’s life, but for its relation to the essay form.

Wish I Was Here by M. John Harrison. In fact I haven’t finished reading this. But I dug what I read, and will go back and finish it, but feel like I wasn’t in the right headspace for it at the time. It’s a book to sit with, to scribble on, to squint, to make work on the page. It’s not a book to do anything as basic as just read.

Sports and Social by Kevin Boniface. Stories from the master of quotidian observation that somehow avoids observational whimsy (the curse of stand-up comedy). If we build a new Voyager probe any time soon this should be on it, but failing that I’d recommend putting a copy in a shoebox and burying it in your garden, for future generations to find.

Thunderclap by Laura Cumming. A slight cheat, as I finished this on the first of January 2024. But it was a Christmas present and perfectly suited the slow, thoughtful last week of the ending year. I loved Cumming’s take on Dutch art, and how its thingness is often overlooked, and I loved the way she mixed together scraps of biography of Carel Fabritius (about whom little is known) and a memoir of her father (James Cumming, about whom little is known to me). The fragments hold each other in tension very well, but it’s not fragments for fragments’ sake. Cumming delineates a space for thinking about art, and its relationship to life, and lives, and other elements, big and small: death, sight-loss, colour-blindness, the nature of explosions, dreams, more. Tension’s not the word: it’s more like a provisional cosmology, that puts thematic and informational pieces in orbit around each other. There’s no symphonic tying-together at the end, but things are allowed back in, with new things too.

I only started underlining (in pencil: it’s a beautiful book!) towards the end. Here are some lines:

- “Open a door and the mind immediately seeks the window in the room”

- “Painting’s magnificent availability”

- Of an explosion witnessed first-hand: “a sudden nameless sound […] a strange pale rain”

There is so little known about Fabritius, with so many of his paintings lost, but really there’s so little known about any of us, the book suggests… and most of our paintings will be lost (as paintings by Cumming’s father have already been lost) but yet looking at art brings a special kind of knowledge, showing us “the intimate mind” of the artist, as of a novelist, or – as here – a writer. The love of art and of life shines through, or not shines, but diffuses, as in one of the grey Dutch skies Cummings writes about.

“But I have looked at art” she says, and she shares that looking (as does T. J. Clarke in his magnificent The Sight of Death) but she also opens up a space for looking. If “But I have looked at art” is an understatement, a compelling gesture of humility, then Cumming can also write, again towards the very end of the book, “What a glorious thing is humanity” and not have it jar, or smack of pomposity. There is much to cherish – much humanity (and what else is there in the world truly to cherish? – in Thunderclap.

Continue readingBooks of the Year 2022

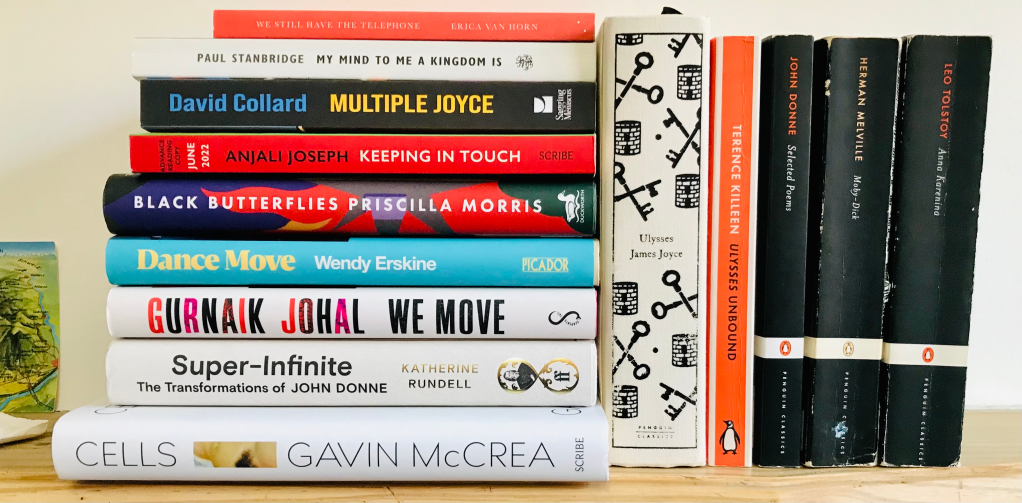

Reading habits and outcomes change according to personal inclination, of course, but also according to external factors: life circumstances, temperament and age, the demands of a job. All of which is to say I’ve read fewer new books this year than in the past. I review less than I used to, certainly, and when I read for work (teaching Creative Writing at City, University of London) I’m more interested in the books that came out a year or two ago, and that have perhaps started to settle into continued relevance, than the whizz-bang must-read of the year.

Of the new books I have read, that have made a lasting impression, here are seven:

Ghost Signs by Stu Hennigan (Bluemoose) is an unforgettable journal of the 2020 Covid pandemic lockdown, during which the author was furloughed from his job working for Leeds City Council libraries and volunteered to deliver food parcels to vulnerable people and families. The eerie descriptions of empty motorways and fearful faces peering round front doors evoke that weird time in 2020, but the true and lasting impact of the book comes from Hennigan’s realisation that the poverty and distress he discovers in his adopted city isn’t down to the pandemic at all, but to entrenched government policies that have forced council services to the brink, and thousands of people into shamefully desperate circumstances. It’s a political book, sure, but one written out of necessity, rather than out of desire or ideology, and one that you want every politician in the country to read, and quickly, so that the responsibility for dealing with the issues it raises passes to them, rather than resting with Hennigan. (That’s the problem with writing books like this, isn’t it? That by being the person who identifies or expresses the problem, you become inextricably linked to it, a spokesperson, a talking head, with all the emotional labour that implies.)

(Ghost Signs isn’t in the photo because I’ve given away or lent both copies I’ve owned.)

I heard Hennigan read from and talk about the book at The Social in Little Portland Street, London this year, and the same goes for Wendy Erskine, who was promoting her second collection of short stories, Dance Move (Picador). Erskine is one of the most talented short story writers in Britain and Ireland today, and I’ll read pretty much anything she writes. Dance Move is at least as good as her first collection, Sweet Home, and if you made me choose I’d say it’s better. The stories are muscly, chewy. Erskine has had to wrestle with them, you can tell. They are worked. She takes ordinary characters and by introducing some element that might be plot, but isn’t quite, she forces their ordinary lives into unprecedented but gruesomely believable shapes. These stories are perfect examples of the idea that plot and dramatic incident should be at once surprising and inevitable. But the thing I love most about her stories (I wrote a blog post about it here) is how she ends them:

You are so immersed in these characters’ lives that you want to stay with them, but the deftness of the narrative interventions means that the stories aren’t wedded to plot, so can’t end with a traditional narrative climax or denouement.

(As David Collard said, in response to my original tweets, “Wendy Erskine’s stories don’t end, they simply stop” – which is so true. Perhaps it would be even better to say, they don’t finish, they simply stop.)

So how does she end them? She kind of twists up out of them, steps out of them as you might step out of a dress, leaving it rumpled on the floor. In a way that’s the true ‘dance move’: the ability to leave the dance floor, mid-song, and leave the dance still going.

Take the story ‘Golem’, definitely one of my favourites in the collection. It’s a story that does everything Erskine’s stories do. It densely inhabits its characters’ lives, and it has its comic-surreal interior moments, but most incredibly of all, it manages to end at the perfect unexpected moment. The story goes on, but the narrative of it ends. It departs, exits the room, taking us with it.

Perhaps the best way to put it is that you feel that, yes, the characters are ready to live on, and yes, you’d be ready to keep on reading the prose and the dialogue forever, but no, you wouldn’t want the stories themselves to last a single sentence longer.

My other favourite short story collection of the year is We Move by Gurnaik Johal (Serpent’s Tail), which is a thoroughly impressive debut, that again seems to show how short stories can be the perfect receptacle for characters: they give us characters, rather than plot, rather even than writing, or prose, or words. The difference between this and Dance Move is that We Move, to an extent, looks like the traditional debut-collection-as-novelist’s-calling-card. I’d love to read a novel by Johal – or for Erskine, for that matter, but equally I’d love her to just go on writing stories, because the more people like her keep writing stories, rather than novels, the stronger and more vital the contemporary short story as form will be.

My Mind to Me A Kingdom Is by Paul Stanbridge (Galley Beggar – publisher of my debut novel, though I don’t know Paul) is an exquisite piece of writing that does live or die by its sentences. (Narrator: it lives). An account of the aftermath of the author’s brother, it is indebted to WG Sebald, in terms of the way it leans on and deals out its gleanings of learning, but also in terms of how its lugubriousness slides at times into a form of humour, or perhaps of playfulness. No mean feat when you’re writing about a sibling who killed himself. A hypnotising read.

My most unexpectedly favourite book of the year was Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne, by Katherine Rundell (Faber), which I wrote about for The Lonely Crowd, here. I didn’t know I needed a biography of a Sixteenth Century English Metaphysical poet in my life, but Rundell fairly grabs your lapels and insists you read him. Frankly I’d read any book that contains lines like “A hat big enough to sail a cat in” and “joy so violent it kicks the metal out of your knees, and sorrow large enough to eat you” in it.

My final new book of the year is We Still Have the Telephone by Erica van Horn (Les Fugitives), which I received as a part of a support-the-publisher subscription. It’s a delightfully sly and spare account of the author’s relationship with her mother. “My mother and I have been writing her obituary” etc. One to file alongside Nicholas Royle’s Mother: A Memoir, and Nathalie Léger’s trilogy of Exposition, Suite for Barbara Loden and The White Dress (also from Les Fugitives) as great recent books about mother-child relationships.

A mention here too for Reverse Engineering (Scratch Books) which is a great idea: a selection of recent short stories accompanied by short craft interviews with their authors. It’s got succeed on two levels: the stories themselves have to be worth reading, and the interviews have got to add something more. It succeeds on both, with wonderful stories from some of our best contemporary story writers: Sarah Hall (at her best the best contemporary British short story writer), Irenosen Okojie, Jon McGregor, Chris Power, Jessie Greengrass etc, and useful commentary. I look forward to reading more in the series.

(Copy not shown in photo as loaned out.)

I’ll include another section here on new books, but new books written by writer friends or colleagues: Cells by Gavin McCrea (Scribe) is a jaw-droppingly raw and honest memoir that bristles with insight, and revelation, and liquid prose. Keeping in Touch (also Scribe) is my favourite yet of Anjali Joseph’s novels, a properly grown-up rom-sometimes-com, that makes you want to get on airplanes, travel the world, travel your own country, wherever that is, talk to people, work people out, and fall in love, which is perhaps the same thing. And Black Butterflies by Priscilla Morris (Duckworth) is a novel I’ve been waiting more than a decade to read, and it didn’t disappoint. It’s a moving and delicate told narrative of the siege of Sarajevo, that perhaps wasn’t best served by its publication date just as something horribly similar was happening in and to Ukraine. Finally, 99 Interruptions is the latest slim missive from Charles Boyle, who published my Covid poem Spring Journal in his CB Editions. It sits alongside his pseudonymous By the Same Author as a perfect short book – with the same proviso that it’s so damned slim that it’s easy to lose. And indeed barely a month after buying it I already can’t find it to put in the photo. No matter. I’ll find it, months or years hence, by accident, and enjoy rereading it all the more for that.

For various reasons, this was a strong year for me for successfully finishing fat chunky classics that I’d tried and failed to read in the past: the kind of book I usually can’t read unless I can organise my life around it.

Continue readingBooks of the year 2021

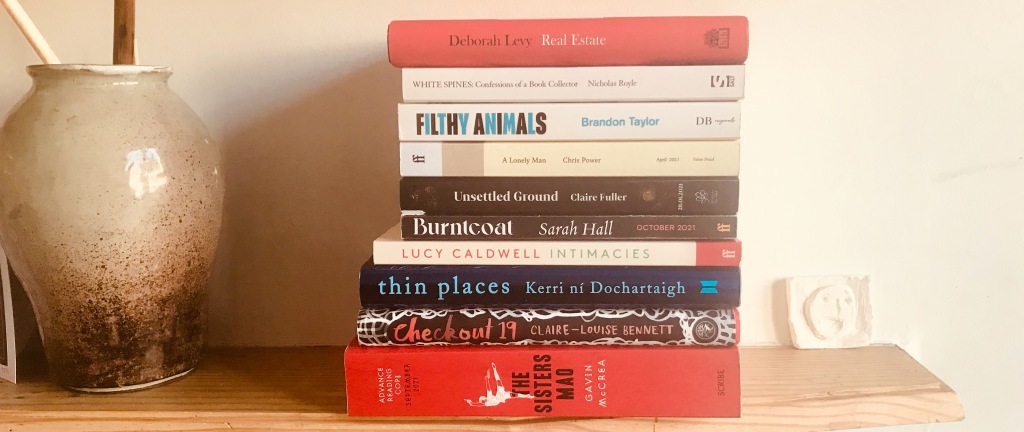

Here then are my best books of 2021 – which I’m limiting to books published in that year.

(Of books read for the first time and not published this year that I loved, I’d mention Sandra Newman’s wondrous The Heavens, Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea, M John Harrison’s Climbers and The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin.)

Looking at this stack, I see some powerfully good writing, some fine novels and short story collections and memoirs variously entertaining (Royle) and painfully exposing (Dochartaigh). Overall, it seems quite a middle-of-the-road selection, and if it seems to me slightly disappointing then perhaps that’s because all but one of the books are by writers I have already read, and so fully expected to enjoy. (Some of the writers, it has to be said, I know personally to a greater or lesser degree: Claire Fuller, Gavin McCrea, Chris Power, Nicholas Royle.)

So let’s say it wasn’t particularly a year of great discovery for me, which is a shame, and something that only really occurs to me as I write this round-up. Books can offer reassurance and comfort, and they can offer the thrill of the new. They are something you can settle into, or something that can unsettle you as it broadens your understanding of the world, and of reading as an endeavour and an experience. Newman’s The Heavens – the only one of those four ‘old’ books mentioned above that was by a new-to-me writer – surprised me as it unfolded, which is perhaps even more rare than surprising you from the off, with a rollicking premise or an unprecedented, irrepressible voice.

The one new-to-me writer on the ‘best of new books’ pile is Kerri ní Dochartaigh, whose memoir Thin Places I read in its entirety on the penultimate day of the year – so it’s possible that it benefits from recency. I didn’t completely love it from the start – there is a tendency, especially in its prologue, towards purple prose, and imagery that seems to be scattered into the prose too incautiously, like herbs in cooking – but it settles into its telling and the rationale of its narrative approach becomes more convincing the clearer it becomes.

The book is the story of a life lived under the shadow of the Troubles and the trauma induced by it, even when the author flees from her home town of Derry. She has a petrol bomb thrown through her bedroom window at the age of 11, her best friend is brutally murdered at the age of 16, her family breaks up and disintegrates, she experiences abusive relationships, addiction and suicidal thoughts. All of this is approached through what might be termed nature writing, as is common elsewhere, but this is done very much in the abstract, through the experience of remembering or recasting experience, rather than trying to take us through the experience as they might have happened. It is contemplative, rather than immersive. It helps, too, that Dochartaigh frames her story through a consideration of the damage that Brexit has done and is still doing to Northern Ireland. She looks outward, and onward, as well as inward, and back. There is repetition in the prose, but this takes the form of slight, extended echo, rather than insistent stuttering. If the writing is intended or effected as a process of healing, then that is because she uses language to stitch sentences – not to close wounds but to fashion bandages. You can see the work the words are doing.

The novel that surprised me the most – that felt most like a discovery – was Claire-Louise Bennett’s Checkout 19, which weaves and leaps with the strangeness of its voice: weirder and more vivacious I think than in Pond, her debut. It is a – possibly – autofictional account of a life lived in thrall to books, with quite simple anecdotes put through the wringer of this way of telling: swerving and recursive, like a childish Beckett making itself sick on sweets. This (non-) story then takes a capricious and absolutely unpredictable left-turn into an account of a ludicrous fictional character called Tarquin Superbus. I said in my original Twitter response that it left me in a state of energised perplexity – “I want to read it again, to see if I can understand it. But I don’t want to understand it” – and although I haven’t yet reread it, I have picked it up and glanced at it, and I do still very much want to reread it.

For the first time in 2021 I built a Twitter thread responding to all the books I finished (you can start it here), with the idea that this would help me with my monthly reading round-up blog posts, though unfortunately it replaced them rather than aided them. I only got as far as May, and then stopped. There were of course reasons for this, but I’m not yet sure how I will proceed next year.

As I’ve said before, this thread, and those posts, only offer a partial account of my reading: they are the books I read from cover to cover, and there are plenty of books I thoroughly enjoyed that I didn’t read completely, most obviously essays and short stories. It is noteworthy that the two short story collections that show up in this pile are ones that lend themselves to reading in full: Brandon Taylor’s phenomenally good Filthy Animals because of the linked stories following a trio of characters that thread through the book, and Lucy Caldwell’s Intimacies because of a more subtle narrative development that means the stories seem to kind of drift into autofiction towards the end, or rather seem to abandon plot development for a more thematic cluster of concerns. Read out of sequence they might seem rather the less for it. I wrote about Caldwell’s book here.

The continuation of my A Personal Anthology project (now approaching two thousand individual short story recommendations) means that I read lots and lots of short stories, but these rarely get mentioned. It would be great to think of a way to make this happen.

My job teaching Creative Writing at City, University of London, means that I also read a lot to work out what books I want my students (undergrad and postgrad) to be reading. This means I half-read a lot more books than I read in full. I half-read a lot of creative non-fiction this year, as I worked up to the launch of the MA/MFA Creative Writing, with its non-fiction strand. You can read about my selection process here.

I’m starting 2022 with a side-project to read Finnegans Wake a page a day in a group read organised by Paper Pills aka @ReemK10, and I have one other idea that may or may not come to fruition. Looking at my 2021 reading I feel the lack of a big classic in there – a Middlemarch, Proust or Magic Mountain. Another Mann is a possibility (Buddenbrooks or Joseph and his Brothers), and with every year that passes the fact of not having read Anna Karenina seems to loom more darkly. Two immediate work reading projects mean that I can’t think about that now.

Finally, my reading is always at odds with my writing. I am close to finishing a first draft of a novel that should have been done a year ago, but then I tell myself that I wrote a book-length poem in 2020 (Spring Journal, which you can still buy of course from the publisher, the brilliant CB Editions), and I launched a postgraduate degree in 2021, so perhaps 2022 will be the year it gets submitted. 2021 did also see the shortlisting of a story of mine – ‘A Prolonged Kiss’ – for the Sunday Times Audible Short Story Award, which was thrilling. You can find the story in its initial publication in The Lonely Crowd, and listen to it read brilliantly on Audible.

Books of the Year 2020

The best books of the year – or rather the books that gave me the best reading experiences. Meaning the deepest, highest, widest, closest, most pleasurable. In all the strange ways we measure pleasure.

Well, I’d better start by saying I finished my complete, first reading of Proust – which I’d started on 1st January 2019 – on 31st May 2020. The plan had been to read the whole thing in a year, but by October 2019 I was still only on volume 4, and the last date that year (I took to writing the date in the margin to mark where I finished reading each day) was 21st October, halfway through that volume. I picked it back up in February 2020, beginning again at the start of vol 4, and made good progress through lockdown. All along I jotted thoughts and posted screenshots on a dedicated Twitter account (@proustdiary), and if I had the time I would try to scrabble together and collate these into something more coherent. It was a major reading experience, yes, full of great highs but also full of longeurs and swampy sections to trudge through. Don’t go reading it thinking it’s like other novels. It’s not.

Other major reading experiences of the year from books not published in the year:

- Middlemarch, read for the first time, on holiday in that odd distant summer window when I was lucky enough (for lucky read privileged) to be able to spend 10 days on a Greek island. Not just a wonderful, exemplary novel, it is also a vindication of the very idea of the Victorian novel, of what it can do: stolid realism, intrusive omniscient narration, all the things we like to think we do without in our literary style today.

- The Third Policeman. I’d tried At Swim, Two Birds before, more than once, and never got far with it, admiring its precocious undergraduate wit without being convinced that it would develop into anything more worthwhile. This one, though, tugged at me from the first pages, and delivered, in all dimensions. The spear, and the series of chests! The lift to the underworld. The ending! My god, the ending. Let me kneel before the scaffold, which must be the best piece of tactical diversionary business in the history of literature. Read it, then let me buy you a beer to talk about it. (By the bye, I’ve been reading Kevin Barry’s Night Boat to Tangier, on and off, this last month or so – for so slight a book, it’s taken a long time to get through – and you think: oh man, you have talent, but you don’t have that bastard’s wicked spear, so sharp it will cut you and won’t even notice. “About an inch from the end it is so sharp that sometimes – late at night or on a soft bad day especially – you cannot think of it or try to make it the subject of a little idea because you will hurt your box with the excruciaton of it.” Recommended to me by Helen McClory, to whom I am grateful.

- Midwinter Break by Bernard MacLaverty. My first by him. The kind of writing I feel able to aspire to. Precise building of characters in the round. All tilting towards a moment. That moment in the Anne Frank House. It made me reconsider VS Prichett’s line about a short story being something glimpsed out of the corner of your eye. That particular scene could have made a great short story, and it would have remained a glimpse. Sometimes, however, a novel can be a heavy and ornate or structurally robust frame or scaffold designed to hold a glimpse, and the glimpse hits home harder than it ever would at the length of a story.

- Autumn Journal. My true book of the year. From March to August I read it every day, as I was writing my own poem, Spring Journal, given out first on Twitter, and now published by CB Editions. I learned so much about metre, and rhyme, from immersing myself in it.

But, of books published this year:

The Lying Life of Adults by Elena Ferrante (translated by Ann Goldstein, Europa Editions, not pictured as lent out) was my novel of the year. Such a relief, to start with, that she was able to follow the Neapolitan Quartet, and with something that was neither a shorter version of those books, nor a return, quite, to the short vicious claustrophobia of the three brilliant standalone novels. It is perhaps less fully distinctive than any of those works – more similar, in scope, to what other people write as novels, but no less pleasurable for that. I read it, along with Middlemarch, on holiday, and it gave me the great pleasure of holiday reading, of allowing reading time to overflow the usually watertight boundaries of hours and activities, of blocking out the world. It’s strange, isn’t it, how we go to lovely places on holiday – places with great views, great landscape, and great climate – and read. I mean, you could lock yourself up in your bedroom and read, for a week, but you don’t. (If you can afford to, you don’t.) There must be something about the climate and landscape that improves the reading, or something about the reading that makes the landscape and climate more precious, for being ignored, or not being made the most of. The Ferrante reminded me of Javier Marías – who, incidentally, I had auditioned for taking on that same holiday, buying Berta Isla in anticipation, but I glanced at it a few times before setting off and, chillingly, found it utterly unappealing and most likely dreadful.

Similar in a way to Ferrante’s quartet was Ana María Matute’s The Island (translated by Laura Lonsdale), another essential discovery from Penguin Modern Classics. I reviewed it on this blog, here. As I say there, it was the incantatory aspect of the narration, calling back over the years to the lost friends, lost love, lost self, that stayed with me from reading it.

2020 saw the publication in translation of Natalie Léger’s The White Dress (translated by Natasha Lehrer, Les Fugitives), the third part of her trilogy of monograph-cum-memoirs that began – in English – with Suite for Barbara Loden, and continued with Exposition (those two were written and published in French in the opposite order). What a set of books these are! As strong on the furious waste of female artistic talent, and the general and specific ways that men, and male social and cultural structures, set out to achieve this end, as anything by Chris Kraus; as simply, naturally adventurous in its manner of navigating its different forms as Kraus or Maggie Nelson. Each book is brilliant, no one of them is put in the shadow by the other two, but the ending of The White Dress – this book is about Pippa Bacca, an Italian performance artist who was abducted, raped and murdered while hitchhiking across Europe to promote world peace – is as sickeningly powerful in its effect as the end of Spoorloos (The Vanishing). You feel helpless. I wrote more about The White Dress in a monthly reading round-up, before these petered out, here.

I chose Nicholas Royle’s Mother: A Memoir (Myriad Editions) and Amy McCauley’s Propositions (Monitor Books) as my books of the year for The Lonely Crowd. They’re both brilliant, and you can read my thoughts on them here.

Another memoir that I devoured, and that gave me tough minutes and hours of thinking and reflection, even as, on the page, it sparked and effervesced, was Rebecca Solnit’s Recollections of my Non-Existence (Granta). In a way it’s the opposite to Royle’s book, which is only ever caught up in the flow of time as if by happenstance. Royle’s mother happened to live through certain years, and be of a certain nationality and generation, so the exterior world does impinge, but impinges contingently. (The book is about personality, and how personalities bend towards, away from and around each other in a family.) Solnit’s book, by contrast, is absolutely caught in the flow of time. Solnit is who she is because of when she lived, and lives. In this it’s somewhat similar to Annie Ernaux’s superb The Years, which I wrote about here, and chose for my Books of the Year in 2018. And it’s as intelligent and insightful as Léger’s books, though Solnit has no reservations about writing about herself. (Léger, you feel, can only write about herself by way of writing about others. She is reticent, and so to an extent subject to the ego. Solnit writes memoir without ego.) This is certainly the book of Solnit’s that I’ve enjoyed the most.

From memoir to essays – and yes there is a lot of non-fiction on this list, among the new books I mean. I’m not sure why this is. There are other contemporary novels and short stories (in collections, journals, on their own) that I’ve read this year that I enjoyed, but none of them impacted on me as heavily as these books. Perhaps it’s because fiction is less concerned with its impact on the reader here and now, it drifts into the timeless time of world and story that must, perforce, be largely unlinked to the phenomenal world. By contrast, all these essays address me, here today, and demand something of me. (Incidentally, timeliness is not a guarantee of meaning. I tried reading Zadie Smith’s ‘lockdown’ essay collection Intimations, and found it rather insipid. It seemed like noodles and doodles, when Solnit, Léger and Ernaux, as good as sat me down and talked important things to me, things that needed to be said.)

I very much enjoyed Elisa Gabbert’s The Unreality of Memory and Other Essays (Atlantic), the essays of which seemed to spring from the world – they are about disaster, ecological crisis, terrorism, things that we know as it were unknowingly. They are unknown knows. The subjects seemed to be held still by Gabbert as if by force of will, in a way that seems different from the other non-fiction pieces mentioned here. They were not a natural outpouring or distillation of insight – as, for example, and famously, was Solnit’s brilliant ‘Men Explain Things to Me’ – but worked pieces, pieces Gabbert had to work at, to get right, topics she had to apply herself to in order understand them, to bring them under the law of her thought. She was forcing herself to think, and we were beneficiaries.

Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence (Fitzcarraldo) is a characteristically intelligent, urbane, distinguished set of essays that focus on particular writers by zooming in on – and then building out from – single sentences of their writing. They are master-classes, and they remind me of Clive James’s Cultural Amnesia, though that book ranged more widely (James ranged more widely, full stop). Suppose a Sentence is wonderful because what it offers is unapplicable. You can’t use it for anything else. Its lessons are oblique. It’s like a walking tour of a part of the city you’d never found on your own, and never will be able to again.

Exercises in Control by Annabel Banks (Influx Press) was perhaps the most interesting new collection of short stories I read this year. The stories are mostly short, and don’t try too hard to be polished or well-rounded, nor to be artfully extraordinary. But they grab you with their insouciance, their not-caring. The story ‘Rite of Passage’, with a girl (I should say ‘woman’) who crawls into hole in a rock on a beach on a date, was thrilling for its unpredictability. It didn’t quite have the courage of its convictions, in the end, but many of the stories left me feeling deliciously unmoored.

Finally, my other book of the year, it goes without saying, was The Snow Ball by Brigid Brophy, reissued by Faber, my favourite novel of one of my all-time favourite writers, who is hopefully becoming better known. This book was, to some extent, the model for my last novel, The Large Door, set, like Midwinter Break, in Amsterdam. I love The Snow Ball with a reader’s passion, that is say excessive, partial, formed by circumstance and transference.

- The following books were courtesy of the publishers: The Island, The Snow Ball, The Lying Life of Adults, The White Dress, Suppose a Sentence. Thank you to Penguin, Faber, Europa Editions, Les Fugitives and Fitzcarraldo.

(Not) Books of the Year 2019

This has not been a good year for me, reading-wise. Last year’s Year in Reading post features a stack of great books published in 2018 that I was able to enjoy and write about as they came out. For various reasons, this year’s stack is much smaller. This might be simply that there weren’t so many good books, or it might be that I lost my taste for them – for books, for reading.

There are some other mitigating circumstances:

First of all, 2019 was supposed to be the Year of Reading Proust, something I set for myself as a new year’s resolution, with a dedicated Twitter account to accompany it, and give me encouragement. It started well, with the first two volumes done over the first two months, but the third wasn’t finished until I was on my summer holiday. The fourth volume, Sodom and Gomorrah, sits by my bed even now. Proust calls for time properly devoted to it – you have to have time to find time, or speculate to accumulate you might say – and time this year was sucked up by other things.

There were four intense reading projects that got in the way: a blitz through some unread Iris Murdochs ahead of a panel discussion at the Cambridge Literary Festival; rereading some Brigid Brophys as I put together a chapter for an academic book; reading and rereading Don DeLillo for another academic chapter; and currently an avalanche of Simenons for a long piece to be published next year. These were and are all fulfilling and exhilarating in their different ways, but ate up much of my reading/writing energy while they occurred.

Work got in the way: academia is becoming more gruelling. (Academia, in part, means reading lots of things fast to find the things I want my students to read more slowly. It means strategic, points-based, results-oriented reading.)

Writing got in the way, for a time: my morning commute, which is often my best time for reading, suddenly gave itself over to the first draft of a new book – that now, alas, languishes at 45,000 words, untouched in two months. I have no idea when I will get back to it.

A Personal Anthology has been a happy distraction: all those short stories to read! Obviously, I don’t read all of all of them, but the project has sent me in many different and rewarding directions.

There were months this year – September and November – when I didn’t read an entire book front to back, though I never stopped reading. Reading just became scatter-gun, fragmentary, a bit of this, a bit of that, snacking, never finding the book that would suck me in and close off the rest of the world. Perhaps this is to do with teaching (I am always looking for useful examples of types of writing, always classifying, always comparing), perhaps with writing (I am always looking for inspiration, for something in a book that will light the fuse under my own writing; a snatch of writing can be enough).

I’m somewhat in that mood at the moment, on the last day of the year. Knowing that I have a big piece of writing work to do in January (academic bureaucracy) and a big piece in February (the Simenons), I find it hard to settle on any book that I feel deserves my full attention.

Or rather I feel I don’t have enough to offer any book that is going to make demands on me, as a reader. And I have too much pride to reach for something that demands nothing from me.

Instead, I reach for books that I think will steady me, will give an intense shot of what I need without having to read all of it – a ‘livener’ I think you’d call it. Something bracing. So, in the last few days I’ve picked up:

- an Alasdair Gray novel from the four I have unread on my shelves. It was Something Leather. It didn’t do the trick;

- a John Berger book I have read before (Here is Where We Meet), hoping that it would match or else steer my self-pitying end-of-year rudderlessness (it didn’t);

- a big book of RS Thomas poems. That did the trick for one bedtime;

- then Alasdair Gray’s wonderful The Book of Prefaces, which is the very definition of the intellectual livener.

- And then see me walking back up the road from the high street, having dropped off a selection of books at the charity shop, reading the opening to Adam Mars Jones’s book of film writing, Second Sight, a steal at a pound, and instantly, though temporarily, feeling invigorated. Here is someone writing insightfully, fruitfully, encouragingly about culture, making it all seem worth while.

None of those books, though, have been read enough to count as Reading. They haven’t been ‘ticked off’.

So if I look back at my Monthly Reading posts from 2019, I find that the new books I read that I loved the most were not new books at all, but just newly translated. Continue reading

Books of the Year 2018

In going back through my Monthly Reading blog posts for the year I’ve identified 12 books published this year that I more than thoroughly enjoyed, that I think are great to brilliant examples of what they do, and that I feel will frame and influence my future reading. (A thirteenth, The Penguin Book of the Prose Poem, is not pictured because I’ve loaned it to someone.)

In going back through my Monthly Reading blog posts for the year I’ve identified 12 books published this year that I more than thoroughly enjoyed, that I think are great to brilliant examples of what they do, and that I feel will frame and influence my future reading. (A thirteenth, The Penguin Book of the Prose Poem, is not pictured because I’ve loaned it to someone.)

A quick scan of the books shows me Faber have had an excellent year – four of the twelve – and it’s no surprise that Fitzcarraldo and CB Editions show up, both publishers very close to my heart. (It’s only fair to point out that those books were complimentary/review copies, as was the Heti and the Johnson. All others bought by me.) And a shout-out to Peninsula Press, whose £6 pocket essays are a welcome intervention to the literary scene. Eight women to four men writers. Only one BAME writer. Two books in translation. Two US writers.

I’m not going to write at length again about each book, but rather provide links to the original monthly blog posts or reviews, but I do want to take a moment again to think about Sally Rooney’s Normal People, which seems to stand out for me as a Book of the Year in a more than personal way. In a year that the “difficulty” or otherwise of Anna Burns’ Milkman (which I haven’t read, and very much want to) became a hot topic, I think it’s worth considering just how un-difficult Rooney’s book is, and how that absence of difficulty, that simplicity, that ease-of-reading – allied to the novel’s clear intelligence – is central to its success, both as a novel unto itself, and more widely. You can see precisely why an organisation like Waterstones would make it Book of the Year: it is utterly approachable; it finds an uncomplicated way of narrating complicated lives and issues.

I read Normal People in September, a borrowed copy, but bought it again recently, and was pleased to find that Marianne and Connell drifted back into my life without so much as a shrug. I think it’s a brilliant accomplishment, while I’m also very aware that this is a book aimed squarely at me: white, middle class, educated. I embrace it because it reflects my situation and concerns, and in addition romanticises and bolsters the generation I now find myself teaching at university. I want it to work, and it does, for me.

Yet I am astonished that it does so much with so little. Present tense, shifting close third person narration. Unpunctuated dialogue. A drifting narrative almost without plot, chopped into dated sections.

I wrote here about how I didn’t want to have to buy it in hardback (though I did) and I wrote here about how these anti-technical techniques made the book a potentially dangerous model for Creative Writing students – it looks like you can get away with Not Much – and it is true that Rooney’s book seems to throw a harsh light on some of the other books on my list, sitting with it in that stack. They seem to be trying so hard: Jessie Greengrass’s Sight is so unashamedly intelligent, Will Eaves’s Murmur so oblique and poetic, Tony White’s The Fountain in the Forest so formally inventive (and in a number of different ways), Sheila Heti’s Motherhood so disingenuous in its informality, its seeming-naturalness. (I hope it’s clear that I love these books for the very aspects I seem to disparage.)

By contrast, Normal People seems written at what Roland Barthes called ‘writing degree zero’, by which he meant writing with no pretension to Literature – “a style of absence which is almost an ideal absence of style”. His model for this is Camus’ L’Étranger, and the comparison seems apt, except that L’Étranger is written in the first person. Everything extraneous is taken out. It’s interesting to note that David Szalay’s All That Man Is is written in a very similar way to Normal People, the only real difference being the use of single quote marks for dialogue. Yet they seem a world apart to me. Continue reading

Books of the Year 2017

The Back of Beyond by Peter Stamm (Granta)

This is my third (or fourth?) Stamm novel, and before I picked it up I was worried I was beginning to settle into something of a pattern with his books. While I’m reading them, I’m transported; the prose – as before, in Michael Hofman’s translation – is impeccable; the situation presented is both eminently plausible and horrifying suggestive. This is realist fiction with the skin peeled off, showing modern human beings (genus: white, usually middle-class Europeans) at their most ordinary, but vertiginous. There, you think, there but for the grace of God – or possibly the grace of Peter Stamm. But, when I think back to some of the previous Stamms I’ve read, I find they have evaporated in my memory, or else reduced themselves to vivid, isolated moments. This one, I can guarantee, will not do that.

The ordinary couple at the heart of the story are a middle-class heterosexual couple, the parents of two young children, just returned from a holiday and preparing for the return to school and work. Only, while Astrid is upstairs, settling their son, her husband Thomas just… walks out. He puts down his wine glass and leaves through the garden gate. Brilliantly, Stamm treats the reader to both sides of this drama, giving us the disappearance and its aftermath in alternating sections told from Thomas and Astrid’s perspective. Novel of the year?

Being Here is Everything: The Life of Paula M Becker, by Marie Darrieussecq, translated by Penny Hueston (semiotext(e)/Text Publishing)

I reviewed this for minorlits, and stand by my assessment, that it is as good as 2015’s Suite for Barbara Loden. They’re similar books in that they’re biographical essays that take a fresh approach to the now familiar job of bringing into the light the lives and work of unjustly forgotten female artists. For both books, that approach involves a personal and fragmentary style that seems to avoid the usual biographical narrative, as if there is something inherently monolithic and stultifying to it, as if it is secretly in service to the patriarchy.

Whereas Natalie Léger’s portrayal of Loden’s treatment by her husband and director Elia Kazan is unambiguously critical, Darrieussecq is more uncertain about the role of the poet Rilke in Becker’s life. They had a close connection. He wrote a long commemorative poem about her on the anniversary of her death, but did not name her in it. He could have done so much more, she deserved so much more. Non-fiction book of the year.

An Overcoat by Jack Robinson (CB Editions)

Charles Boyle’s CB Editions is one of my favourite indie presses. It’s a true one-man operation, based on Boyle’s excellent taste, no-bullshit attitude and willingness to stand in line at the Post Office with an armful of Jiffy bags on a regular basis. So I was sad at this year’s news that the press is going into semi-retirement – but I was cheered by the arrival, this year, of not one but two small books by Boyle himself, writing under his pen name Jack Robinson. Robinson is a righteously angry book about Britain, Brexit, boys’ schools and the legacy of colonialism, but it’s An Overcoat that has stuck with me, for its delightful hop, skip and a jump along that unstable line that separates fact from fiction.

In it, Henri Beyle (known to most of us as Stendhal, author of The Red and The Black) finds himself in an afterlife in small-town England. He hangs out in cafes, tries to date a woman called M, treats the life of contemporary Britain to the dispassionate observation we wish we had time and the eyes for. Unbeknownst to him, however, the book’s author is annotating the narrative with reference to Beyle’s life and work. It is about as far removed from an academic book on Stendhal as you could imagine, but it is very true to his spirit – true to Boyle’s lifelong love of his writing – as well as being true to the spirits of, for example, WG Sebald, Rachel Cusk, Patrick Keiller. Boyle is one of Britain’s best publishers. He is also one of its most intriguing experimental novelists. If he sold as many books as he deserves to, he’d be a National Treasure, and we cannot allow that to happen. Neither-one-thing-nor-the-other of the year.

Blue Self-Portrait by Noémi Lefebvre (Les Fugitives)

In my review of Blue Self-Portrait for the TLS I described it as Bridget Jones as told by Thomas Bernhard, which was glib. But what Lefebvre does, that is at least partly Bernhardian, is treat the neuroses of her female narrator as worthy of close attention. The book is a plotless wonder, a short ride in the fast machine of a narrator’s overheating, near-to-stalling consciousness – in this instance, a woman flying back from a city break in Berlin to her home town of Paris, accompanied by her sister. Mostly what she’s thinking about is the German male composer she met there and had drinks with, but didn’t accompany back to his apartment – though the romantic aspect of their not-quite-relationship is the least of it. This is neither a love story, nor its opposite. It is about personhood, about how we dare to try to be someone different from other people, and the risks that this entails.

Under My Thumb, edited by Rhian E Jones and Eli Davies (Repeater Books)

I picked this up on spec in Waterstones at Waterloo (good that they’re giving table space to indies like Repeater, which is run by the former staff of Zero Books) in part because I’m writing a novel at the moment set in the music industry – that treats, in part, the issue of sex, as in the issue of groupies, as in the issues of misogyny and sexual predation. I’m trying to address the difficult question of whether it is possible to even imagine rock and pop music without sexual oppression, and the slightly more straightforward question of what we should do about rock and pop stars who abused their power to sexually manipulate women, and girls, in the past.

What’s useful, for me, about this collection of essays is how the authors put their own love of music (rock, pop, hip-hop, soul) on trial. How can you deal with the fact that you love the Stones, Spector, Tupac? How and when is it possible to separate the art from its creator? Standout articles include Fiona Sturges on her love for AC/DC, which she was able to pass on to her daughter until it came to the idea of seeing them live, and Frances Morgan on Michael Gira from US alternative band Swans, who has been accused of abusive behaviour by an ex. Morgan is a fan, and has interviewed the musician in the past. Her essay is a thoughtful exploration of her feelings around the situation and the ethical implications. There have many similar pieces since the Weinstein vocalisation, but this was written before that explosion. The book is full of women thinking carefully about their responses to the actions of culturally significant men. As such, you might call it a mirror for magistrates.

My House of Sky: The Life and Work of JA Baker, by Hetty Saunders (LIttle Toller)

I was looking forward to this book ever since the estimable Little Toller books launched their crowdfunder for it. JA Baker was the author of The Peregrine, one of the seminal works of contemporary nature writing, published in 1962. It’s a strange book that is short on what you’d call proper ornithology, and very much faces in the opposite direction to the whole ‘nature as therapy’ subgenre that has led to books like H is for Hawk. It follows Baker’s obsessive hunt for the falcon across the reclaimed coastal landscape of the Essex coast over a series of winters. (It’s a landscape I know well from my childhood, as the son of an Essex birdwatcher; I found it dull then, but – no surprise – am haunted by it now.) Baker made a point of identifying himself with the peregrine in his book, but it’s the land, not the bird, that he seems to disappear into.

The Peregrine was a big success, but Baker wrote one only other book, which flopped. Other than that, he stuck to his marriage, his Chelmsford council house and his birdwatching, but suffered from encroaching ill health until his death in 1987, at the age of 61. Saunders has done a good job in fleshing out the mystery as best she can, and the book is beautifully produced, with reproductions of Baker’s maps and notebooks that recall Rachel Lichtenstein and Iain Sinclair’s book about David Rodinksy. But in truth Baker was no Rodinsky, and what there was in him that was interesting, you’d have to think, he successfully poured into his one great book. So, while this is a book that was called for, and one to cherish, it is perhaps a slight disappointment for those of us who had invested so much in the areas of Baker’s map that had previously been so tantalisingly blank. Some blank areas on the map, I suppose, are blank because there’s simply nothing there.

Essayism, by Brian Dillon (Fitzcarraldo)

A brilliant disquisition on the essay form, that successfully sidesteps the pitfalls of that particular meta-form, which include banging on about Barthes, Montaigne and Sontag all the time, and coming across as immensely pleased with yourself. Thankfully, Dillon is as self-lacerating as he is intelligent, and this book (like The Dark Room, which I reviewed back in the day, and which Fitzcarraldo are bringing out in a new edition next year) is an acute piece of self-criticism, repeatedly backing into short, unexpected jolts of memoir. It also quotes one of my very favourite passages, from one of my very favourite books, something that made me shout with joy when I saw it.

The Red Parts: Autobiography of a Trial, by Maggie Nelson (Vintage)

I was blown away by The Argonauts when I read it last year, and so I leapt at the chance to read Bluets (2009) and The Red Parts (2007) when Vintage reissued them this year. Bluets I found a little dull (I wrote about it, sort of, here), but The Red Parts gripped me completely. It is Nelson’s account of the trial of Gary Earl Leiterman for the murder of Jane Mixer, Nelson’s mother’s sister, 36 years earlier. It is not a piece of true crime. It is an investigation of various emotional states, and of the ability of writing to capture these, and the risks involved in this. It had me thinking about James Ellroy (whom I used to read a lot) long before Nelson lays into him, decisively. This isn’t quite as mind-shifting as The Argonauts, and it does make me wonder what Nelson will write next. She has a lot to live up to.

After Kathy Acker, by Chris Kraus (Allen Lane)

A third biography in my selection: I seem to be conforming to the stereotype of the reader who drifts from novel-reading to biographies as they age. Why? Well, because, knowing more of the world, you are more able to measure non-fiction against it; and because what comes naturally as a teenager and young adult – imagining yourself into the character of any protagonist – becomes harder as you see how options fall away from around you the further through life you go. I am not particularly interested in Acker as a writer – I tried reading Blood and Guts in High School, sent to me alongside a proof of this biography, and found it pretty repulsive, to be honest. But clearly she was an interesting person, and sometimes the price of learning about and understanding interesting people, and their place in the culture, is reading their books. After all, at the time when Acker was doing the interesting things she did (which included writing books whose interest lay elsewhere than in what they were actually saying), there was no Kraus to write about her. Now there is, and Kraus proves herself an admirable biographer. Parts of I Love Dick were rather heavy on the critical theory, but she is clear about Acker’s dalliance with theory what she brings to bear on Acker, in London, LA and New York, is always clear, always credible. She is also generous with her attention, looking, as does Darrieussecq in her book about Modersohn-Becker, to the partners of important artists, when their work has sometimes been unjustly overshadowed.

The Proof, by César Aira, translated by Nick Caistor (And Other Stories)

This is the third Aira that I’ve tried, and the first one that really clicked. I’m beginning to appreciate his modus operandi – partly thanks to a great interview in The White Review (No. 18). But still it’s hard to align his immense prolificness and imagination to the paradigm of modern publishing. Yes, Simenon wrote a hell of a lot, but with Simenon you knew what you were getting. The hit rate here seems less sure. But there is something so blissfully uninhibited about this short narrative, with its sexy, punky intro and its ascent into glorious, excessive violence, that makes perfect sense.

small white monkeys, by Sophie Collins (Book Works)

I’ve amended this post to make this an actual eleventh book of the year, rather than an addendum. It’s a brilliant, forthright essay about shame written by Collins (primarily a poet; she was in the first of the Penguin New Poets series earlier this year alongside Emily Berry and Anne Carson) as part of a project undertaken at the Glasgow Women’s Library. I bought it online directly after reading an extract published on the White Review website. Read that, and you might do the same.

(The pamphlet visible to the right is ‘Spring Sleepers’ by Kyoto Yoshida, one of a series of new stories from Stranger’s Press, a new publishing project from UEA. Beautifully produced, and some really intriguing stories.)

Books of the Year 2016

Transit, by Rachel Cusk (Jonathan Cape)

I loved Outline, and I love this, its sequel and the second in a projected trilogy. Transit shares with the earlier book its dispassionate writer-narrator, Faye, and a super-cool novelistic intelligence, and the simple but effective premise that Faye narrates her dull, everyday encounters – with her ex, her hairdresser, her Albanian builder and others – without explicitly ever giving her side of the conversation.

We get what they say in direct speech, but what she says only in paraphrase. She is utterly reserved, absent in except in her reflections, appraisals, judgements. There is no plot arc, no sense that any of these people suspect that this person is spending the entirety of their time together processing and narrating it, rather than committing to the encounter on equal, human terms.

The risk with these books is that they avoid the tricks writers usually use to make their stories stick in your memory, and this does mean that they start to lose traction the moment the reading ends. Six months on, all I could really remember from Transit was two great set-pieces: a damp literary festival, and the Cotswolds dinner party that ends the book.

This isn’t one of the great dramatic, explosive literary dinner parties (think of James Meek’s We Are Now Beginning Out Descent), but what it is, is true to life, rather than true to books. Doubly so, in fact. It is realistic both in how these kinds of things pan out, and in how we see them as they’re doing their out-panning, from behind a pane of glass called consciousness.

I remembered, too, that the book ended brilliantly, that it makes most novel endings seem bluntly contrived.

This is the Place to Be, by Lara Pawson (CB Editions)

I reviewed this in brief for The Guardian (not available online, alas) and it’s hung around in my head, as I knew it would from the moment I opened it on the tube. Brilliant and uncompromising is what I said in the review, but there is more to it than just the brutally candid reflections of a one-time BBC correspondent on her time reporting in war-torn Angola, and on what awaited her when she tried to re-enter ordinary life.

The book’s brilliance is in its discovery of a form to match the subject matter. This is the Place to Be is written in fragments, in unindented block paragraphs separated by white space. Sometimes the link between paragraphs is obvious, sometimes not, sometimes tangential, sometimes delayed. Writing in fragments is a risky business, but this is textbook stuff. (Literally so, if I ever get around to writing the book I want to.) Continue reading

Books of the year 2015

Suite for Barbara Loden, by Nathalie Léger, trans. Natasha Lehrer and Cécile Menon (Les Fugitives)

Reading is all about discovery, so this book had me primed for maximum impact. Why? Well, it’s a new translation of a book by a French writer I’d never heard of, about an American actor I’d never heard of, and specifically her sole directorial outing, which scarcely anyone ever has heard of. Wanda (1970) is out of print on DVD, and only turns up very rarely indeed on the festival circuit. Yet, while I’d jump at the chance to see it, at the end of this distinctive and thoughtful piece of writing, I certainly felt like I’d got a handle on it, or rather a handle on what Léger, the author, thinks of Loden, the actor, and on what Loden thinks of her film’s hero, Wanda, and, through her, the elusive, fugitive woman on whose story her movie is based. In hugely reductive terms, this is Geoff Dyer’s Zona meets Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick: an open and intelligent piece of art criticism that drifts into broader critique of social and cultural issues, and is honest about the fact that it can’t do any of these without also being autobiographical. That it is published in a beautiful edition that gives a boutique twist on the classic French livre de poche style, by a brand new British publisher proudly asserting their ownership of an important but overlooked niche, only adds to the charm. Book of the year.

I Love Dick, by Chris Kraus (Tuskar Rock)

All the stuff about the dissolving boundaries between fiction and non-fiction comes together in this revelatory novel-memoir-cultural critique, which has been steadily spreading its influence since its original publication in the US in 1997. The book starts out as a playful wallow in the abasement of unrequited love and failed creativity – as film-maker ‘Chris Kraus’ becomes besotted with a sexy ex-pat sociologist – and ends up performing a measured but comprehensive demolition of the cultural apparatus that is organised to mispresent and devalue her experience, both private and public. If Miranda July’s The First Bad Man set out to eviscerate the idea of the female author as ‘quirky’, then perhaps this does the same for ‘hysterical’. Kraus weaponises the language of critical theory by hauling it out of its safe zone (safe for men, safe for the status quo) and exposing its blandly sexist foundations – exposing herself and others in the process. It’s a high-wire act, and naturally I am reading it very differently from people who were involved or close by at the time, but, as with Knausgaard, we the readers are in the privileged position of being able to distinguish ends from means, and what Kraus comes up with seems more important than any toes she stepped upon during the process. It’s not written with the ‘general reader’ in mind, and I skimmed some of the Deleuze and Guattari bits, but this is off-set by some brilliant, scathing, undiluted writing about desire, and the differing strangenesses of coupledom and – is this a word? – singlitude.

(I reviewed I Love Dick for The Independent: here) Continue reading

A year in reading: 2014

I haven’t been keeping a strict list of books read during 2014 so this won’t be a strict list of best books, but rather a recollection of the most memorable reading experiences. Which itself leads to an interesting question. How much does a book have to stay with you after finishing it for it to be a good book? I ended my TLS review of Mary Costello’s remarkable Academy Street with the observation that I wasn’t sure if Tess was “the kind of character to stay with the reader long after the book is closed, but during the reading of it she is an extraordinary companion.”

I was discussing the book with David Hayden of Reaktion Books, and the name Deirdre Madden sprung up, whose latest novel Time Present and Time Past I’d just read. I said that I’d hugely enjoyed her earlier book Molly Fox’s Birthday, and that although that judgment stood – that it was a good book – I honestly wouldn’t have been able to tell you anything that happened in it at all.

What books have stayed with me, then? For new novels, Zoe Pilger’s helter-skelter semi-satire Eat My Heart Out and Emma Jane Unsworth’s more groundedly rambunctious Animals both offered up visions of contemporary Britain that I found winning and accurate, or appropriately overdone. Unsworth’s had the thing I thought Pilger’s lacked (though there was more at stake in Pilger) – a sense of where the character might be heading at the end of the dark trip of the narrative. Thinking back on Pilger’s book now, it occurs to me – and I wonder if it’s occurred to her– that Anne-Marie would make a superb recurring character. She’s great at showing where London is, a decade or so into the century. She’d be a useful guide to future moments, too.

The characters I spent the most time with over the year were Lila and Elena from Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels, aka My Brilliant Friend. I read the first volume early in the year, having been previously blown away by the gut punch/throat grab/face slap of The Days of Abandonment. I read the second and third Neapolitan volumes on holiday in the summer. I was reviewing it, so my proof copy is full of scribbles, but the scribble on the final page of Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay says just: ‘Wow’. As has been said before, these books do so many things – European political history, female friendship, anatomisation of Italian society, child to adult growth and adult to child memory – but it does two things that I found particularly powerful. Continue reading