Tagged: roland barthes

Out of photographs into words: Nathalie Legér’s Exposition, Barthes and the mother-child photograph

Nathalie Léger’s Exposition is the first in a loose trilogy of books published in French between 2008 and 2018. Formally they mix essay, criticism and memoir. In each of them Léger focuses on the work of a woman engaged in making art in some way either provocative or running counter to the prevailing cultural mood, and each of them pulls back from that woman to consider the art form in which they’re working, and then to reverse, as it were, into the author’s own life.

Nathalie Léger’s Exposition is the first in a loose trilogy of books published in French between 2008 and 2018. Formally they mix essay, criticism and memoir. In each of them Léger focuses on the work of a woman engaged in making art in some way either provocative or running counter to the prevailing cultural mood, and each of them pulls back from that woman to consider the art form in which they’re working, and then to reverse, as it were, into the author’s own life.

Although Exposition (2008) opens this trilogy, it was not the first to appear in English. That was Suite for Barbara Loden (2012), about the film actor and director of that name. (All three books are or will be published in the UK by Les Fugitives. I wrote about Barbara Loden here.) Loden’s sole film as writer and director, the American new wave landmark Wanda, remains a cult favourite, though hopefully she will in future be better known for that than for being Elia Kazan’s second wife.

The third book, The White Dress (2018), treats Italian performance artist Pippa Bacca, who in 2008 hitchhiked from Milan to Jerusalem wearing in a wedding dress to promote world peace; she was raped and murdered in Turkey.

(The White Dress is forthcoming from Les Fugitives and I will be talking with Léger about it at the Institut Français in May.)

What follows is some thoughts on Exposition, following an event last week at The Photographers’ Gallery, at which I discussed the book with its translator, Amanda DeMarco.

Exposition takes as its subject the Countess de Castiglione, Virginia Odioni (1837-1899), an Italian aristocrat who took Paris by storm in the 1850s – though see how young she still was! – and was briefly mistress of the French Emperor. (Again, how young.) She was famed for her beauty and her narcissism, and was later rejected by the court, and ended her life more or less in squalor. Through all this she was obsessed with having her photograph taken, returning again and again to the same society studio, in good times and bad, for elaborate photographs – in costume, role-playing with props and accessories – taken to her own specification. (Shades of Cindy Sherman, as Léger notes in her book, and also of selfie-culture, though Léger doesn’t mention that: the iPhone 4 with front-facing camera wasn’t released until 2010, two years after Exposition‘s original publication.)

Exposition is partly a book about ideas of beauty, then, and partly about photography. It pays homage to classics of the genre such as Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida, without particularly seeking to insert itself into that genealogy. Léger turns away from Castiglione to write about photography, turns away from photography to write about writing, turns away from writing to write about herself – and her mother.

This aversion to straightforward narrative is played out through Léger’s loyalty to the fragment as form. She constructs her books from island-paragraphs that float unmoored on the white space of the page, with little attempt to make meaning or argument flow between them. You have to hop from one to the next. Which is not to say that there is no order to what is presented; the links are there to be made by the reader. What narrative flow there is works slowly, and at depth. Continue reading

Books of the Year 2018

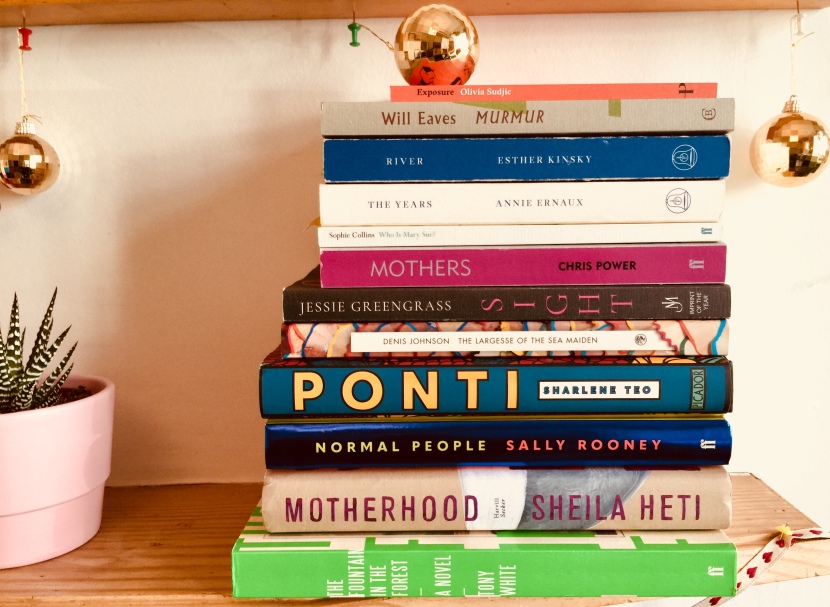

In going back through my Monthly Reading blog posts for the year I’ve identified 12 books published this year that I more than thoroughly enjoyed, that I think are great to brilliant examples of what they do, and that I feel will frame and influence my future reading. (A thirteenth, The Penguin Book of the Prose Poem, is not pictured because I’ve loaned it to someone.)

In going back through my Monthly Reading blog posts for the year I’ve identified 12 books published this year that I more than thoroughly enjoyed, that I think are great to brilliant examples of what they do, and that I feel will frame and influence my future reading. (A thirteenth, The Penguin Book of the Prose Poem, is not pictured because I’ve loaned it to someone.)

A quick scan of the books shows me Faber have had an excellent year – four of the twelve – and it’s no surprise that Fitzcarraldo and CB Editions show up, both publishers very close to my heart. (It’s only fair to point out that those books were complimentary/review copies, as was the Heti and the Johnson. All others bought by me.) And a shout-out to Peninsula Press, whose £6 pocket essays are a welcome intervention to the literary scene. Eight women to four men writers. Only one BAME writer. Two books in translation. Two US writers.

I’m not going to write at length again about each book, but rather provide links to the original monthly blog posts or reviews, but I do want to take a moment again to think about Sally Rooney’s Normal People, which seems to stand out for me as a Book of the Year in a more than personal way. In a year that the “difficulty” or otherwise of Anna Burns’ Milkman (which I haven’t read, and very much want to) became a hot topic, I think it’s worth considering just how un-difficult Rooney’s book is, and how that absence of difficulty, that simplicity, that ease-of-reading – allied to the novel’s clear intelligence – is central to its success, both as a novel unto itself, and more widely. You can see precisely why an organisation like Waterstones would make it Book of the Year: it is utterly approachable; it finds an uncomplicated way of narrating complicated lives and issues.

I read Normal People in September, a borrowed copy, but bought it again recently, and was pleased to find that Marianne and Connell drifted back into my life without so much as a shrug. I think it’s a brilliant accomplishment, while I’m also very aware that this is a book aimed squarely at me: white, middle class, educated. I embrace it because it reflects my situation and concerns, and in addition romanticises and bolsters the generation I now find myself teaching at university. I want it to work, and it does, for me.

Yet I am astonished that it does so much with so little. Present tense, shifting close third person narration. Unpunctuated dialogue. A drifting narrative almost without plot, chopped into dated sections.

I wrote here about how I didn’t want to have to buy it in hardback (though I did) and I wrote here about how these anti-technical techniques made the book a potentially dangerous model for Creative Writing students – it looks like you can get away with Not Much – and it is true that Rooney’s book seems to throw a harsh light on some of the other books on my list, sitting with it in that stack. They seem to be trying so hard: Jessie Greengrass’s Sight is so unashamedly intelligent, Will Eaves’s Murmur so oblique and poetic, Tony White’s The Fountain in the Forest so formally inventive (and in a number of different ways), Sheila Heti’s Motherhood so disingenuous in its informality, its seeming-naturalness. (I hope it’s clear that I love these books for the very aspects I seem to disparage.)

By contrast, Normal People seems written at what Roland Barthes called ‘writing degree zero’, by which he meant writing with no pretension to Literature – “a style of absence which is almost an ideal absence of style”. His model for this is Camus’ L’Étranger, and the comparison seems apt, except that L’Étranger is written in the first person. Everything extraneous is taken out. It’s interesting to note that David Szalay’s All That Man Is is written in a very similar way to Normal People, the only real difference being the use of single quote marks for dialogue. Yet they seem a world apart to me. Continue reading

Gone in the blink of an eye: Elizabeth Bowen’s contingent realism

I’m reading Elizabeth Bowen for the first time and finding it a slow-going but exhilarating experience – perhaps the closest comparison, in terms of necessary application to the page, is Javier Marías, someone else who won’t be rushed, whose paragraphs flow like dark syrup, not clear water.

One of the things that has most struck me – and that is very different from Marías – is the utter contingency of Bowen’s descriptions. Things are always shown in the light of the moment, not with any definiteness; so much so that you’d almost think that, were you to glance away from the page, and back again, the words on it would have changed, with the movement of a cloud across the sun, or the bough of a tree across a window.

As such, she is working very much against received ideas of ‘realism’ in prose writing, against what Henry James called “solidity of specification”. There is no solidity here; everything is always on the point of dissolution – and this sense of unreality is surely no accident; Bowen extends it to her characters:

The sun had been going down while tea had been going on, its chemically yellowing light intensifying the boundary trees. Reflections, cast across the lawn into the lounge, gave the glossy thinness of celluloid to indoor shadow. Stella pressed her thumb against the edge of the table to assure herself this was a moment she was living through – as in the moment before a faint she seemed to be looking at everything down a darkening telescope. Having brought the scene back again into focus by staring at window-reflections in the glaze of the teapot, she dared look again at Robert, seated across the table, between his nephew and niece.

Obviously the syntax is a brake on understanding; Bowen seems fusty and old-fashioned in her sentences, leaping back over Virginia Woolf towards the likes of James, even when what is being broached in those sentences – the sheer ephemerality of self-consciousness – is as modern as anything by Woolf. Stella (the main character of The Heat of the Day) has to steady herself by looking at the reflections of the windows caught in the glaze of the teapot before she can dare to look at her lover. Why ‘dare’? Well, because she’s scared that when she looks for him, where he was sitting only a moment before, he will have disappeared, sparked out of existence. Continue reading

December reading: Mann, Arendt, Bataille, Chandler, and Ken Worpole and Jason Orton

You know those people who reread Ulysses every year? I hate those people. Those with long memories may remember that the book I was reading as 2013 began was Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain.

Well, I can now reveal that the book I’m reading as the new year turns is… again, The Magic Mountain. Or, rather, still The Magic Mountain.

This wasn’t a reread, oh no. This was the same, first read. I just hadn’t finished it yet. Other books had been read in the meantime, of course, and for most of the year I wasn’t reading it at all. But I picked it back up, in November, turned back 50 or so pages, and pressed on.

It’s a slow, hard read, this book, a slow, hard climb. But the views, when you pause and turn and take stock, are jaw-dropping, the flora underfoot often charming, and the intellectual air bracing to say the least.

Set in the years before the First World War, Mann’s novel opens with young, healthy (in body and mind) engineer Hans Castorp visiting his soldier cousin Joachim in a Swiss sanatorium, where the latter is being treated for tuberculosis. The three week visit turns into a temporary and then indefinite stay when he develops first a temperature, and then is found to have “a moist spot” in his chest.

The narration of these three weeks, I feel it must be said – and the author feels it needs pointing out too – takes up over 200 pages, during which there is a lot of talk, a lot of ideas tossed artfully around, much of which is intriguing enough when it occurs, but little of which I could safely summarise for you now. Does this matter? I’m not sure that it does. There has been no point in this book at which I have not wanted to read on; as Mann puts it in his foreword, “only thoroughness can be truly entertaining.”

Foremost among the brilliancies of the book is that Mann is especially alert to the fact and activity of reading; he is constantly concerned with how the novel will appear from the far side of the textual abyss. In the foreword he warns that the story is going to take more than a moment or two to tell. “The seven days in one week will not suffice, nor will seven months […] For God’s sake, surely it cannot be as long as seven years!”

After those three weeks, easily demarcated in the text, time starts to act weirdly, and how long the events of the rest of the narrative are supposed take is never quite clear. Which in fact makes it perfect for this kind of uncertain and extended reading that I have been giving it: reading, in fact, that becomes as cyclical and seasonal as Hans Castorp’s stay in the sanatorium. Up there in the Swiss Alps, in that strange pre-war time (when Weimar Berlin, for instance, was being highly temporally specific) time expands and contracts; it exists in a very different to way to the time in Proust. There, the past is something gone, that must be sought out to be retrieved. Here, the past is never truly past, it floods up and engulfs the present. Time (and illness) is something to be escaped, not found again. Continue reading