Tagged: Lorrie Moore

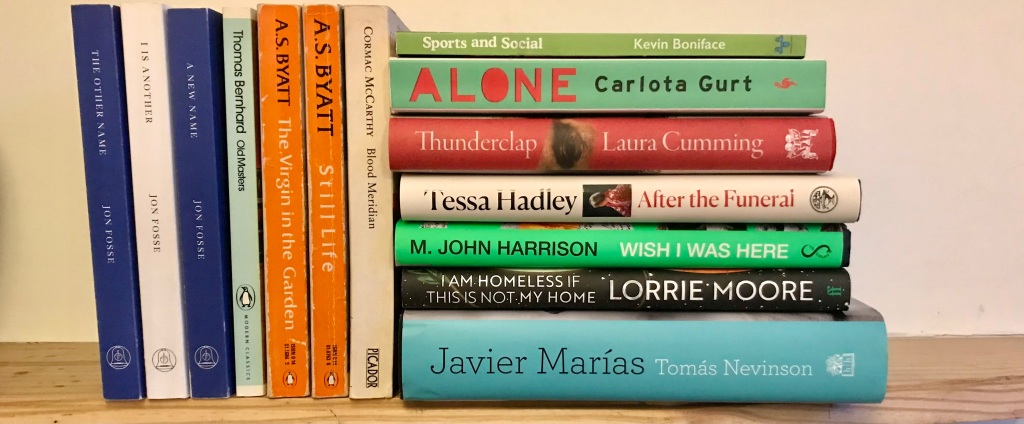

Books of the Year 2023

As for the last few years, I’m reading fewer new books, in part as my university teaching replaces book reviewing as the driver of much of my ‘strategic’ reading, and in part perhaps because of my continued and always-belated attempted to catch up with unread classics (2023: War and Peace; 2022: Moby-Dick, Ulysses, Anna Karenina; 2019-20: In Search of Lost Time; Middlemarch; 2024? I’m not sure yet…)

Anyway, here are my ‘books of the year’ – I’m keeping the title for consistency’s sake, though really this is intended as a record of my reading. In 2023, as I’ve done in some of my previous years, I kept a ‘reading thread’, which migrated halfway through the year from Twitter/X to Bluesky. (I’m keeping my X account live, really just for the purposes of promoting A Personal Anthology; I’ve deleted it from my phone, and carry on my book conversations now on Bluesky). I’m grouped the books according to i) new books, i.e. published in 2023 ii) books read by authors who died in 2023 iii) other books, with a full list at the end.

Best new books

After the Funeral by Tessa Hadley was my book of the year. She is truly a contemporary master of the short story. I delight in her rich use of language, in her ability to draw me into characters’ lives and particular perspectives (though I’m aware that, in broad sociological terms, those characters are very much like me) and in the power and deftness with which she manipulates the narrative possibilities of the short story. She’s like an osteopath, who starts off gently – you think you’re getting a massage; you feel good; you feel in good hands – but then she does something more dramatic, leaning in and applying leverage, and you feel something shift, that you didn’t know was there. ‘After the Funeral’ and ‘Funny Little Snake’ are both brilliant stories well deserving of their publication in The New Yorker. ‘Coda’ is something else: it feels more personal (though I’ve got no proof that it is), more like a piece of memoir disguised as fiction, which is not really a mode I associated with Hadley. I read or reread all her previous collections in preparation for a review of this, her fifth, for a review in the TLS, and I have to say: there would be no more pleasurable job that editing her Selected Stories – the collections all have some absolute bangers in them – though equally I’d be fascinated to see which ones she herself would pick.

Tomás Nevinson by Javier Marías, translated by Margaret Jull Costa. Not a top-notch Marías, but a solid one: Nevinson is a classic Marías sort-of-spook charged with tracking down and identifying a woman in a small Spanish town who might be a sleeper terrorist, from three possible targets, which naturally involves getting close to and even sleeping with them. I found some of the prose grating – flabbergastingly so for this writer (“we immediately began snogging and touching each other up” – I mean, come on!) – but the precision of the novel’s ethical architecture is absolutely characteristic.

Alone by Carlota Gurt, translated by Adrian Nathan West. A compelling and moving Catalunyan novel about the stupidity of thinking you can sort your life out by relocating to the country. Similar in theme to another book I read this year (Mattieu Simard’s The Country Will Bring Us No Peace) though I liked that one far less. I won’t say much about it as I read it without preconceptions and recommend it on the same terms. I will say it reminded me of The Detour by Gerbrand Bakker, which is another novel of solitude and the land, which again benefits from stepping into as into an unknown locality.

I am Homeless if This is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore. Oh boy. I love love love Moore at her best and though this aggravated as much as delighted me it’s been nagging me ever since I really want to go back and read again. [NB I have gone back to it, as my first book of 2024, and am being far less aggravated than on the first read). After a brisk, unexpected and exhilarating opening the novel seems to go into stasis, a slow series of disintegrating loops. It fails to do the thing that Moore usually seems to do quite effortlessly: keep you dizzily engaged with a cavalcade of daft gags and darkly sly sharper wit and observation. The protagonist, Finn, seems to miss what Moore usually gives her central characters: a dopey friend to dopily muddle through life with. He has a brother, Max, but he’s dying, and an ex, Lily, who, well… But all of this is done in flat dialogue wrestling with the big questions. Moore usually lets the big questions bubble up from under the tawdry minutiae of life (as, brilliantly, in A Gate at the Stairs); here, they’re front and centre. More tawdry minutiae, I say! I think part of my frustration with the novel comes from a place of ‘Creative Writing pedagogy’. Wouldn’t it be better, I think, to open up Finn’s character, show him as a teacher, his banter with the students, and his entanglement with the head’s wife? Rather than making all of that backstory, dumping it into reflection. The scene with Sigrid, for instance – her attempts to flirt with Finn – would be stronger if we’d already met her in the novel, already seen their relationship (such as it is) in action. You tell students, first you establish the ‘normal’ of the protagonist’s existence, then you throw it into confusion. So, am I giving LOORIE MOORE MA-level feedback? Well, yes. To which the response (beyond: “she’s LORRIE MOORE”) is: she’s not writing that kind of ‘normal’ novel. For every bit of LM brilliance (the gravestone reading “WELL, THAT WAS WEIRD”; the line “Death had improved her French”) there’s something off, that should or could be fixed or cut: the cat basket sliding around on the car backseat; the scene where Finn’s car spins off the road.

A Thread of Violence by Mark O’Connell. A suavely written book that digs into the true crime genre but stops short of the moral reckoning it at least flirts with: that in truth it shouldn’t exist – as a published book, at least. Will surely sit on reading lists of creative non-fiction in the future.

Tremor by Teju Cole. Read quickly and carefully (in physical not mental terms: it was bought as a Christmas present and sneakily read before being wrapped up and given ‘as new’), with the full intention of going back and reading it again. Cole is a literary intelligence for our times, that I’d drop into the Venn diagram of the contested term ‘autofiction’, not for its supposed relationship to the author’s life, but for its relation to the essay form.

Wish I Was Here by M. John Harrison. In fact I haven’t finished reading this. But I dug what I read, and will go back and finish it, but feel like I wasn’t in the right headspace for it at the time. It’s a book to sit with, to scribble on, to squint, to make work on the page. It’s not a book to do anything as basic as just read.

Sports and Social by Kevin Boniface. Stories from the master of quotidian observation that somehow avoids observational whimsy (the curse of stand-up comedy). If we build a new Voyager probe any time soon this should be on it, but failing that I’d recommend putting a copy in a shoebox and burying it in your garden, for future generations to find.

Thunderclap by Laura Cumming. A slight cheat, as I finished this on the first of January 2024. But it was a Christmas present and perfectly suited the slow, thoughtful last week of the ending year. I loved Cumming’s take on Dutch art, and how its thingness is often overlooked, and I loved the way she mixed together scraps of biography of Carel Fabritius (about whom little is known) and a memoir of her father (James Cumming, about whom little is known to me). The fragments hold each other in tension very well, but it’s not fragments for fragments’ sake. Cumming delineates a space for thinking about art, and its relationship to life, and lives, and other elements, big and small: death, sight-loss, colour-blindness, the nature of explosions, dreams, more. Tension’s not the word: it’s more like a provisional cosmology, that puts thematic and informational pieces in orbit around each other. There’s no symphonic tying-together at the end, but things are allowed back in, with new things too.

I only started underlining (in pencil: it’s a beautiful book!) towards the end. Here are some lines:

- “Open a door and the mind immediately seeks the window in the room”

- “Painting’s magnificent availability”

- Of an explosion witnessed first-hand: “a sudden nameless sound […] a strange pale rain”

There is so little known about Fabritius, with so many of his paintings lost, but really there’s so little known about any of us, the book suggests… and most of our paintings will be lost (as paintings by Cumming’s father have already been lost) but yet looking at art brings a special kind of knowledge, showing us “the intimate mind” of the artist, as of a novelist, or – as here – a writer. The love of art and of life shines through, or not shines, but diffuses, as in one of the grey Dutch skies Cummings writes about.

“But I have looked at art” she says, and she shares that looking (as does T. J. Clarke in his magnificent The Sight of Death) but she also opens up a space for looking. If “But I have looked at art” is an understatement, a compelling gesture of humility, then Cumming can also write, again towards the very end of the book, “What a glorious thing is humanity” and not have it jar, or smack of pomposity. There is much to cherish – much humanity (and what else is there in the world truly to cherish? – in Thunderclap.

Continue readingMarch & April Reading 2021: Lockwood, Moore (Lorrie), Levy, Moore (Susanna), Nelson, Garner, Hall, Musil

At the start of 2021 I began an open-ended Twitter thread listing and commenting on my reading as I finish each book. This was supposed to help with these monthly round-ups, to save time, which clearly didn’t work at the end of March, as I didn’t post a round-up at all. So, for this two-month round-up I’ll be picking and choosing and expanding on those thoughts on some but not all of what I’ve read, rather than going through it doggedly.

It took me a bare couple of hours to read No One is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood, and I’ve spent at an hour elsewhere reading reviews and thinkpieces about it. Which only goes to show, as someone on here pointed out, that it’s the least well-titled book of the year. Unless she means it ironically. Or post-ironically. Or whatever.

I did really like the book, but also I found it exasperating and even anxiety-provoking. The short, fragmentary sections are clearly designed to mimic Twitter, but unlike Twitter you seem to have to read every one of them, as if there is something to ‘get’ from each of them.

This was confusing. On Twitter, after all, you skim through a dozen tweets in as many seconds before you deign to give one your more considered attention, sometimes scrolling back up to read one you initially skimmed over. Your micro-decisions about what to give your attention to are affected by names, and digital paratexts like avis and retweet and like counts. You don’t get that with tweet-length paragraphs on the page of Lockwood’s novel, but equally the usual narrative paraphernalia that allow you to speedily and efficiently navigate a story are also absent. Even Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation had more flow and propulsion across its narrative islets than this.

Of course you acclimatise, and for a while you drift through the novel, picking up little dopamine hits for identifying memes and moments. The incest advert. The plums poem. But the pace of reading picks up, and the drifting becomes sliding, and it takes a great line to slow you down. Thankfully there are plenty of great lines.

Then Something Happens, plot-wise, and this is where the real challenge for the novel lies. Having established a vehicle of utter affectlessness in the first half (even while critiquing and despairing over the same), can it step up and deal with a subject that demands genuine emotional engagement?

Well the answer is no, for me at least. The emotion is there, and if you’ve read the interviews and perhaps even if not you’ll know it’s real, but the novel simply cannot express it. None of the usual, traditional functional parts – the filters and switches – are present, or work as required. It’s as if the book knows it’s trapped, and wants to break out of the trap it’s built for itself – and that’s part of the project after all, that’s what so many of us want to know: is there a way through this way of being, that will lead to another, better one?

What’s missing is the connective tissue. Now, the online world, when we are in it, does contain a connective tissue, of sorts: what gets called ‘the discourse’ (as in: the discourse is particularly toxic this morning). The discourse is the suspension (in the scientific sense) in which the individual tweets float, and take their context, and to which they all, infinitesimally, add.

The point of the novel seems to be that this way of connecting with the world is leaving us adrift and unfulfilled. But when Lockwood gets to the second part of the novel, when tragedy drags her away from the Portal and immerses her in real life, the novel doesn’t change. It’s still written in that atomised, fragmentary style. Is that because this is the only way the narrator can think the world into being? Or is it intended to show the inability of ‘interneted narrative’ to represent the deep continuum of real life? Would it have been a failure of form if Lockwood had ‘reverted’ to a more traditional narrative style to cope with what happens ‘off-screen’?

No One is Talking About This is a tragedy of form, because although it allows me to empathise with the narrator when she is feeling sad about her unconnectedness, it fails to make me empathise when she suffers genuine tragedy. And it’s the form that engineers that failure.

Anagrams by Lorrie Moore was an impulse re-read. It has such a wonderfully idiosyncratic form – four short stories followed by a novella, all featuring the same three characters in different versions and permutations: anagrams of themselves, in other words. Here’s what I said when I read it for the first time on holiday, back in 2013. “These people are us! They are us squared!” is clearly me trying to channel Moore. But it’s true that Moore does use humour to set up devastation. And in fact I’d forgotten quite how bleak the end of Anagrams is.

Continue readingJanuary Reading 2021: DeLillo, Moore, Townsend Warner, Power, Oyeyemi, Rooney, Fuller

This post is built out of my year-long reading thread on Twitter, but expanded.

I started the year with a short Don DeLillo blitz, research for an academic chapter I’m writing. Some of this was rereading, but Americana, his 1971 debut, was one I hadn’t read before. It is strangely split into different parts, as if moving through different tonal landscapes, which is not an approach I associate with this writer.

The opening is a zippy corporate media satire – at times like Joseph Heller’s Something Happened, published three years later – with lots of cynical male advertising executives trying to screw each other over, and screw each other’s secretaries. It then diverts into a long dull suburban childhood flashback, and then goes on a Pynchonesque road trip across the country, fantasmagorical in parts, skippably dull in others.

My conclusion on Twitter was: In the end I suppose I’m just not in the market for these old myths – which, now that I think about it, is basically a paraphrase of the opening line of Apollinaire’s Zone: “À la fin tu es las de ce monde ancien.” Unlike for Pynchon’s freewheeling carnival of invention, I got the feeling I was supposed to care for these characters, in their struggle to care about themselves, and there were simply too many unexamined assumptions that don’t align with my own for that to apply. It tries too hard to be cool, to shock, to provoke; it flails around to distract you from the fact it doesn’t know what it wants to mean, but as a debut novel it’s still hugely impressive and quite powerful.

I also zoomed through Great Jones Street (1973) and Running Dog (1978). In all these books DeLillo seems to be pushing against the novel form, wanting to find some other way of getting through than via a standard plot arc. Great Jones Street is interesting because of what it says about celebrity, and about music – which is a subject DeLillo has never really returned to. Running Dog to an extent is interesting about the mystique that arises when art and money converge, but he mishandles the thriller plot he starts off by gleefully satirising. The ultra-hardboiled dialogue boils dry, with pages and pages of interchangeable spooks tough-talking each other in the backs of limousines. There is an impressively destructive ending – as destructive as Great Jones Street, but really you get the sense that he’s given up before we even get there. By ‘given up’, I mean given up trying to find a way to resolve the plot in a way that honours equally his characters, his themes, and any remaining sense of reality/realism/credibility.

More on novel endings later in this post.

After DeLillo I moved onto A Gate at the Stairs by Lorrie Moore, which I’ve tried to read at least once before, but didn’t get far into. As with Moore’s best stories it made me absolutely snort with laughter on a regular basis. It also ends wonderfully and movingly and, in a way, thrillingly – doing that thing that I think DeLillo has tried to do, to move outside or above the confines or sphere of novelistic plot: not just giving you what you think deserve from what has come before.

It’s clever in the way it stretches what could have been a fine long short story to over 300pp, but there’s too much stodge: more childhood flashback than is necessary (with Americana, is this a lesson?), even bearing in mind the emotional ballast it contributes to the payoff at the end, and too much compulsive-idiosyncratic detail, delivered by the bucketload. This last is of course a familiar aspect of Moore’s short stories, and perhaps she simply though that the same intensity of narratorial gaze can be endlessly extended without consequence, but it ain’t so.

Lorrie Moore’s short stories work because we can only bear to spend so much time with her characters.

To which her characters would doubtless say, Imagine what it’s like being us!

To which I’d say, That’s not how this works.

Continue reading“Let’s give every last fucking dime to Science”: Lorrie Moore and Sarah Churchwell on the Importance of the Humanities

Image courtesy St Mary’s University, Twickenham

Last night I attended a lecture by Professor Sarah Churchwell to celebrate the launch of a new BA Liberal Arts degree at St Mary’s University, Twickenham, on the importance of the Humanities. It seems a necessary statement to make. The university where I teach is opening a Humanities degree at a time when departments in that field are closing around the country (History in Sunderland; English at Portsmouth), and there have been concerns over the future of the sector as a whole. People who work in it are feeling defensive, with the sense the Government is only interested in STEM subjects, or in subjects that can be taught in a narrowly vocational way, leading to defined, definite, concrete jobs.

Churchwell spoke about the value and the necessity of the study of the Humanities, drawing links between American Blues (we had just heard a version of Catfish Blues played by a fusion group mixing Blues with classical Indian instrumentation), slavery, film archiving, the Holocaust, and fascism and the ideology behind America First – the subject of her last book.

She spoke, too, about current global issues like the Coronavirus epidemic, saying that medical knowledge here is not enough, as you can’t learn from a medical emergency in real time: “You won’t stop an epidemic if you don’t understand politics, human behaviour, history.” And the same goes for the migration and refugee crisis: “Everything happens in a political, social, historical, medical context, and the Humanities’ business is the understanding of context.”

She spoke, too, about the advances of technology, and how it’s not enough to have the technical skills to invent new machines and mechanisms; you’ve got to understand the social and ethical effects they bring into play. Her example here was Facebook. By not understanding – and not caring to understand – the implications of uncontrolled and unregulated political advertising on his platform, he allowed the undermining of democracy in the 2016 American election.

Her lecture made me think of Lorrie Moore’s brilliant short story ‘Dance in America’ (you can hear Louise Erdrich read it on the New Yorker podcast here). The story is about a probably 30-something dance teacher visiting an old college friend during a work trip teaching ‘Dance in the Schools’ in rural Pennsylvania. The friend – Cal – lives in a big old unrenovated former frat house with his wife, Simone, and their son Eugene, who is seven years old, and has cystic fibrosis – which is likely to kill him before he even reaches adulthood.

The story is partly about the narrator’s self-image as a former performer (artist) gone to seed and second-rate work, and it’s partly about how how we conceptualise and respond to our impotence in the face of illness and mortality. (It’s about other things too: it’s one of Moore’s best stories.) The relation between these two things is laid out clearly quite early on the story, when Cal says to Moore’s dancer (we haven’t met Eugene yet, only been told about him):

“It’s not that I’m not for the arts,” says Cal. “You’re here; money for the arts brought you here. That’s wonderful. It’s wonderful to fund the arts. It’s wonderful; you’re wonderful. The arts are so nice and wonderful. But really–I say, let’s give all the money, every last fucking dime, to science.”

What is wonderful about the story is that it does not contradict that sentiment, but it shows how we as people are bigger than it. Cal and Simone, he a college teacher, she a painter, don’t treat Eugene as a problem to be solved or saved by science, but as a person. And so does the Moore’s dancer. That’s what the Humanities do; they do put our problems in context, and – Churchwell was very clear on this point – they critique that context.

Studying the Humanities (or the Arts) don’t make you a better person, Churchwell said, and Moore’s protagonist is a great example of that. She is a disappointed, self-deprecating – and self-deprecated – person, as much ruined by chronic irony as buoyed up and saved by it. A classic Lorrie Moore character, in other words. She spouts opaque homilies about the value of art that she doesn’t even pretend to believe in herself (“My head fills with my own yack”), and relies on knee-jerk superiority towards the people who are unimpressed by her exertions (“They ask why everything I make seems so ‘feministic’. ‘I think the word is feministical,’ I say.”)

But what she can do, faced the terrible exuberance, wit and lust-for-life embodied in the questioning, curious, imperious person of Eugene, is dance. When it is bedtime, she leads the family in their nightly routine of dancing – to Kenny Loggins – and “march, strut, slide to the music. We crouch, move backward, then burst forward again.” When Eugene is too tired to continue, she stands with him, and moves more slowly, responding to his needs, to his context.

She does all this almost without thinking, almost intuitively. But that’s the difference between the Arts and the Humanities. The Arts can be instinctive, and intuitive. It’s the Humanities’ job to do that thinking, that analysis, that contextualising for them. Moore doesn’t labour the point – she doesn’t return to the question of how and whether the Arts (and the Humanities) can or should measure up to Science, but she shows that what they do is different, and compatible, and both equally necessary.

Certainly, I think Churchwell would be more concrete in her pushback against Cal’s “give every last fucking dime to science”. What? You think simply chucking money at the problem would make it go away? ‘Science’ is not an all-knowing, all-seeing, altruistic entity that cures diseases with a wave of a magic wand. It is embedded and embodied in human structures, and it is those structures – not the petri dishes in the lab – that the Humanities want to, and need to, muscle in on and critique. Science doesn’t just march, strut and slide forwards. It crouches, moves backward, then bursts forwards.

Say Science comes up with a cure for Eugene’s Cystic Fibrosis, but then wants to sell it to him for $272,000 per year? What does that do to Cal and Simone? Does their health insurance cover it? I doubt it, seeing as their dining room has saucepans in it to catch rainwater. ($272,000 is the current cost in the US of the drug Orkambi, the best current fit for extending lives of sufferers. It has been estimated that the cost of generic version of the drug is $5,000 per year.)

Art can’t do what Science can do. It can’t cure disease. It can console us and distract us and energise us, and help us understand why we’re bothering to try. The Humanities are a necessary corollary to the whole process. They provide the context – the continually evolving, continually self-critiquing context – in which both Science and Art can try to improve the quality of our lives. As Moore has it:

I am thinking of the dancing body’s magnificent and ostentatious scorn. This is how we offer ourselves, enter heaven, enter speaking: we say with motion, in space, This is what life’s done so far down here; this is all and what and everything it’s managed—this body, these bodies, that body—so what do you think, Heaven? What do you fucking think?

The Humanities help us ask that question.

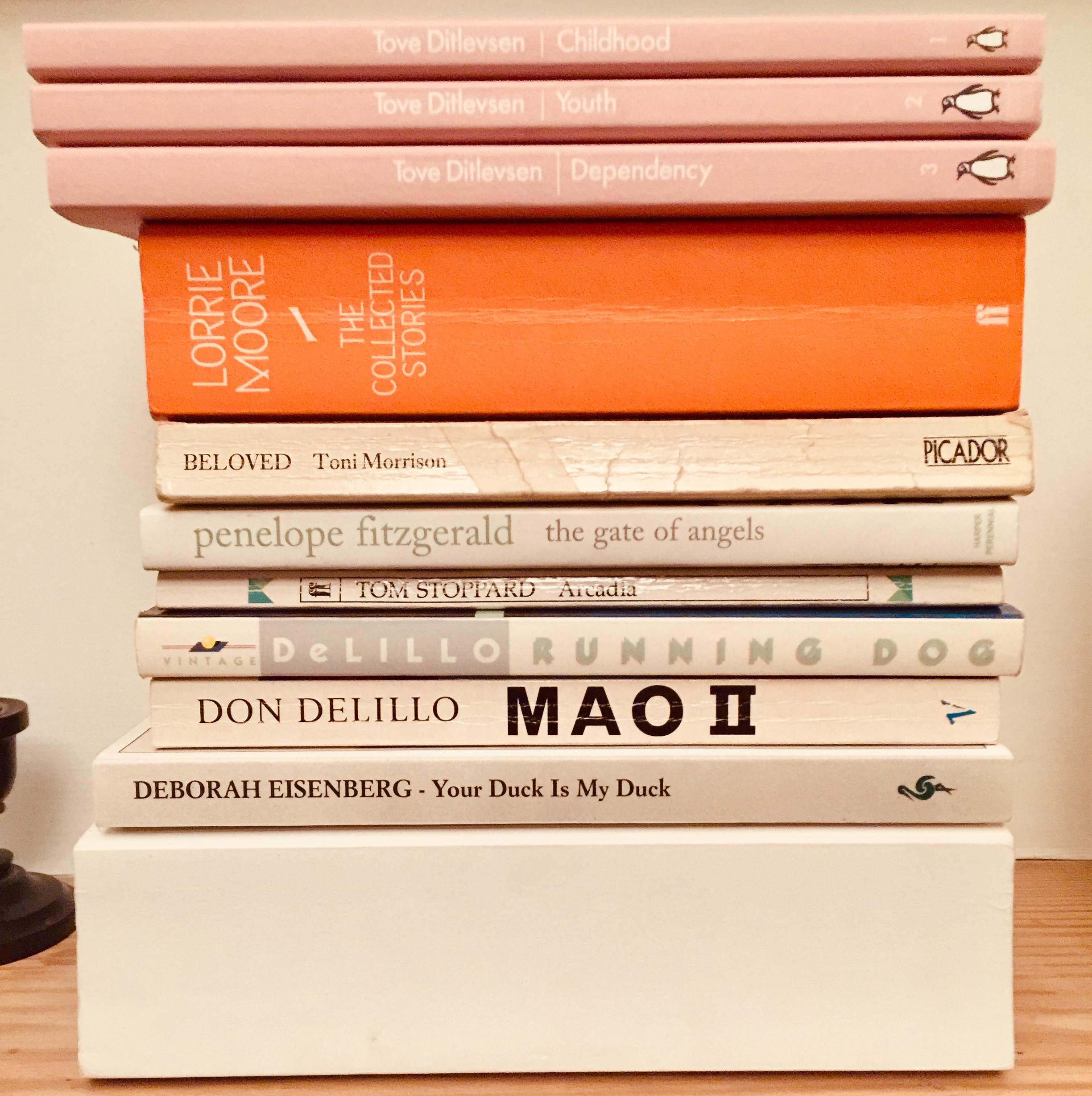

August Reading: DeLillo, Ditlevsen, Eisenberg, Ellmann, Moore, Morrison, Proust

(What a pleasingly alliterative set of author names)

(What a pleasingly alliterative set of author names)

There’s an epigraph that I often remember, from Dave Eggers’ debut A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius (2000 – and boy I wonder if anyone’s read or reread that book recently. It would be an interesting experience.) In fact the book has two memorable epigraphs: firstly, ‘THIS WAS UNCALLED FOR.’; and, secondly:

First of all:

I am tired.

I am true of heart.

And also:

You are tired.

You are true of heart.

Both of them sum up the radical sincerity and potential mawkishness at the heart of his writing. Both, because of this, are memorable. They stay with me, because as statements they are so widely applicable – they are applicable now – as well as being pertinent to the book for which they act as curtain raisers, or perhaps, rather, mottos painted on the safety curtain of the book’s theatre.

I am tired. Teaching starts next week. Summer’s over. I am sure that you are tired. I make no claims for the trueness of either of our hearts, but let’s accentuate the positive.

I am tired. That’s it. That’s the tweet.

And but so:

Books are wonderful relaxation. They are also wonderful energising. There’s nothing I love more than grabbing my phone to tweet a response to something I’m reading, whether it’s Don DeLillo describing a woman putting a condom on a man’s penis as “dainty-fingered and determined to be an expert, like a solemn child dressing a doll”,

No big deal, just a DeLillo sentence describing someone putting a condom on a penis. Fuck sake, Don. pic.twitter.com/i5oBTEN1ly

— Jonathan Gibbs (@Tiny_Camels) August 31, 2019

or Lorrie Moore pole-axing the reader with the devastating end to the first page of her story ‘Terrific Mother’.

Here is the first page of ‘Terrific Mother’. Who else would *dare* to open a story like that? pic.twitter.com/vr4qFHJFXR

— Jonathan Gibbs (@Tiny_Camels) August 22, 2019

I’ve been trying to read Proust with my phone to hand, too, as an enhanced form of annotation, and that, too, has been fun and exciting.

Fun and excitement: wow. That’s it. That’s the tweet.

But, sometimes, writing about books can be a chore. It’s a terrible thing that a book, once read, even a good book, can be put on one side and forgotten. What’s the point of all of this, you think, if a book that engages your brain and emotions over a number of hours over a number of days just gets put back on the shelf and, to all intents and purposes, forgotten? Because sometimes they are picked up again. Sometimes they are passed on. My August reading contained left-turns and blind alleys, slogs up stony hills and brief gleefully shrieking slides down sandy dunes. There was reading for work, reading for the soul, reading by accident and reading by design.

The Don DeLillos are there for an academic chapter I’m writing, and I found myself zooming through them. Mao II, a re-read, is far from my favourite of his novels: too slick and portentous, too glib in the way it throws around its themes.

In one aspect at least it’s a victim of its success. The famous riff about terrorists having replaced the novelists at the heart of the inner life of the culture is blandly prophetic, but it’s too on the nose. The other ‘prophetic’ moments or images in his novels – such as the most photographed barn in America, or the playing dead response to the Airborne Toxic Event, are more oblique, more generally symbolic. The writing is spiffing. It’s spiky poetry has just become too easy to read.

Running Dog, by contrast, I enjoyed. I don’t think I’d read it before. It’s more corny in its plotting – closer to a spy thriller or a contemporary hardboiled thriller – and that allows the author to have more fun, and for the punchier writing to stand out from the more familiar skeleton. Another extract I tweeted managed to pick out something that occurred to me elsewhere about the male (I think) approach to language. Here it is: Continue reading

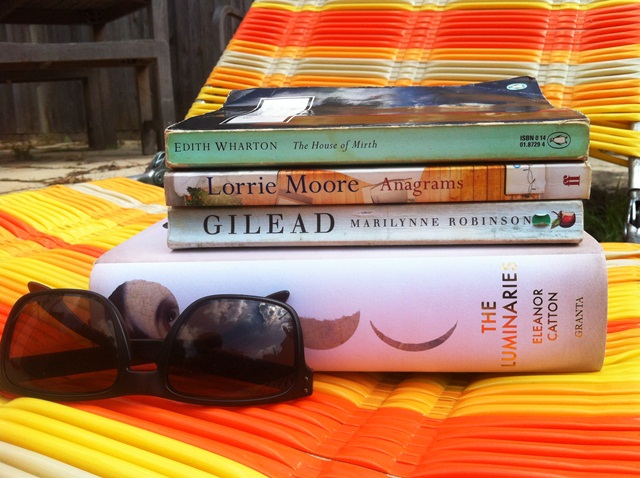

August Reading: Catton, Wharton, Moore, Robinson

August, August, August… disappearing into the rear-view mirror of the year, always the saddest sensation. Gone the sun, gone the skip and bounce in the day, gone the time for reading.

I am now firmly stuck in the middle part of life where August means school holidays, which means a couple of weeks away somewhere hot, which means camping and a pool or beach and the opportunity to read unencumbered by home life and academic/journalistic imperatives, while the kids divebomb around me. But I can read what I want.

What I took away with me this year was Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries (sadly leaving behind Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers because of space considerations), and three paperbacks from my Myopic/Misogynist reading list of women writers: Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth, Lorrie Moore’s Anagrams and Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead.

The Luminaries, in a way, is the perfect intelligent person’s holiday read. It is a mystery story (keeps you reading), and a meticulously built historical fiction (allows you to drift away into a fully-imagined, fully-upholstered reverie), but it is also presented via a structure as intricate and labyrinthine as a spider’s web (you need to have the time to concentrate). Like the other ‘big book’ on the Man Booker longlist, Richard House’s The Kills, it wouldn’t necessarily be something you’d want to read in snippets, tired, at bedtime. Both are fractured narratives, with various versions of events orbiting a ‘truth’ that the reader is tasked with putting together themselves.

Of course, the risk with this – with all mystery stories, i.e. with all stories that include the past as a dimension to be explored – is that the myriad possible ‘truths’ thrown up in the earlier sections of the book may well be tastier meat than the ‘true’ truth exposed at the end. Continue reading

April reading: White Review Short Story Prize, Ben Lerner… but mostly: why I read so few women writers, and how you can help me kick the habit

Okay, so here’s my pile of books from April. Some can be dispensed with quickly: the Knausgaard I wrote about here; the Tim Parks was mentioned in my March reading, about pockets of time and site-specific reading; the Jonathan Buckley (Nostalgia) was for a review, forthcoming from The Independent; the White Review, though I read it, stands in for the shortlist of the White Review Short Story Prize, which had my story ‘The Story I’m Thinking Of’ on it.

In fact, a fair amount of April was spent fretting about that, and I came up with an ingenious way of not fretting: I read all the other stories once, quickly, so as to pick up their good points, but I read mine a dozen times or more, obsessively, until all meaning and possible good qualities had leached from it entirely, and I was convinced I wouldn’t win. Correctly, as it turned out, though I’m happy to say I didn’t guess the winner, Claire-Louise Bennett’s ‘The Lady of the House‘, the best qualities of which absolutely don’t give themselves up to skim reading online. It’s very good, on rereading, and will I think be even better when it’s read, in print, in the next issue of the journal.

That leaves Jay Griffiths and Edith Pearlman. Giffiths’ Kith, which I have only read some of, I found – as with many of the reviews that I’ve seen – disappointing. Where her previous book, Wild, seemed to vibrate with passion, this seems merely indignant, and the writing too quickly evaporates into abstractions. In Wild, Griffiths’ passion about her subject grew directly out of her first-hand experience of it – the places she had been, the things she had seen, lived and done – and the glorious baggage (the incisive and scintillating philosophical and literary reference and analysis) seemed to settle in effortlessly amongst it. Here, the first-hand experience – her memories her childhood – are too distant, too bound up in myth.

The Pearlman – her new and selected stories, Binocular Vision, I will reserve judgement on. It’s sitting by my bed, and I’m reading a story every now and then. The three that I’ve read (‘Fidelity’, ‘If Love Were All’ and ‘The Story’) have convinced me that she is a very strange writer indeed, and perhaps not best served by a collected stories like this one.

Those three stories are all very different, almost sui generis, and each carries within itself a decisive element of idiosyncrasy that it’s hard not to think of as a being close to a gimmick. They all do something very different to what they seemed to set out to do. They seem to start out like John Updike, and end up like Lydia Davis. Which makes reading them a disconcerting experience, especially when they live all together in a book like this. It makes the book seem unwieldy and inappropriate. I’d rather have them individually bound, so I can take them on one-on-one. Then they’d come with the sense that each one needs individual consideration. More on Pearlman, I hope.

The book that I was intending to write more on, this month, was the Ben Lerner, Leaving the Atocha Station, which I read quickly (overquickly) in an over-caffeinated, sleep-deprived fug in the days after not winning the White Review prize, which also involved a pretty big night’s drinking.

But my thoughts about Lerner are very much bound up in a problem which is ably represented by the book standing upright at the side of my pile: Elaine Showalter’s history of American women writers, A Jury of Her Peers. This was a birthday present from my darling sister, who, if I didn’t know her better, might have meant it as an ironic rebuke that I don’t read enough women writers. Continue reading

June Reading: Sebald, Clark, Joseph, Barthelme, Ridgway, Moore, Updike

This month I finished reading two books that had been lying open – by my bedside, on my desk – for months and months: WG Sebald’s Rings of Saturn (a re-read) and TJ Clark’s The Sight of Death. Obviously, this makes them the opposite of page-turners – page-turn-backers, perhaps, as, with the Sebald especially, I found myself going back and starting chapters over, settling myself back in to whichever slippery, slow-moving digression he was taking me on. With the Clark the stop-start process was not a problem. I knew what I was reading it for: I was reading it for insight, for ideas about how we look at paintings, and what it means to come back and look at paintings over and over again, day after day, rather than assume that we can take them in at one glance.

It’s a marvellous book about art, that exhibits its authority not in the range of its reference (though that’s there), but in the focus of its attention. In it Clark spends a six-month sabbatical sitting in a gallery looking at two paintings by Poussin, giving his thoughts not in a clever post-hoc essay, but in diary form, as they come. It makes me want to read Martin Gayford’s Man With a Blue Scarf, his book about sitting for a portrait by Lucien Freud, which presumably has as much to say about the day-to-day process of art on the other side of the aesthetic divide.

Clark’s book might have something to say about why I’ve chosen, or ended up, reading the Sebald in slow, overlapping, self-replicating waves, rather than a simple linear progression. He is particularly good on the importance of the viewing position in front of the painting, something that is impossible to recreate with any kind of reproduction – and boy the reproductions in The Sight of Death are good, dozens and dozens of details on high-gloss paper, magnified crops to illustrate whatever point Clark is making. I went to see one of ‘his’ Poussins in the National Gallery last week, and it was – in its current condition, or lighting, or situation – a sad and muddy mess: impossible to make out even half of what the book shows us, but then Clark is all about the contingencies of the moment: the hanging, the room in the gallery, whether the lights are on or off, the weather outside. He says:

So pictures create viewing positions – don’t we know that already? Yes, roughly we do; but we have only crude and schematic accounts of how they create them, and even cruder discussions of their effects – that is, of how the positions and distances are or are not modes of seeing, modes of understanding, intertwined with the events and objects they apply to.

Every time he goes back to look at the painting he must reorient himself in front of it, let himself work his way back in. Does something similar happen with books? Perhaps. The key problem with Sebald, for me, is how you should negotiate the information he gives you. Continue reading