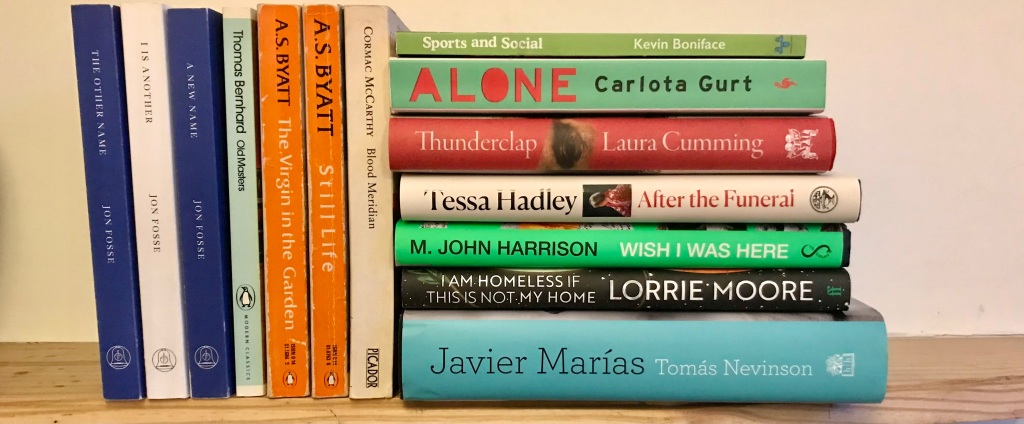

Books of the Year 2023

As for the last few years, I’m reading fewer new books, in part as my university teaching replaces book reviewing as the driver of much of my ‘strategic’ reading, and in part perhaps because of my continued and always-belated attempted to catch up with unread classics (2023: War and Peace; 2022: Moby-Dick, Ulysses, Anna Karenina; 2019-20: In Search of Lost Time; Middlemarch; 2024? I’m not sure yet…)

Anyway, here are my ‘books of the year’ – I’m keeping the title for consistency’s sake, though really this is intended as a record of my reading. In 2023, as I’ve done in some of my previous years, I kept a ‘reading thread’, which migrated halfway through the year from Twitter/X to Bluesky. (I’m keeping my X account live, really just for the purposes of promoting A Personal Anthology; I’ve deleted it from my phone, and carry on my book conversations now on Bluesky). I’m grouped the books according to i) new books, i.e. published in 2023 ii) books read by authors who died in 2023 iii) other books, with a full list at the end.

Best new books

After the Funeral by Tessa Hadley was my book of the year. She is truly a contemporary master of the short story. I delight in her rich use of language, in her ability to draw me into characters’ lives and particular perspectives (though I’m aware that, in broad sociological terms, those characters are very much like me) and in the power and deftness with which she manipulates the narrative possibilities of the short story. She’s like an osteopath, who starts off gently – you think you’re getting a massage; you feel good; you feel in good hands – but then she does something more dramatic, leaning in and applying leverage, and you feel something shift, that you didn’t know was there. ‘After the Funeral’ and ‘Funny Little Snake’ are both brilliant stories well deserving of their publication in The New Yorker. ‘Coda’ is something else: it feels more personal (though I’ve got no proof that it is), more like a piece of memoir disguised as fiction, which is not really a mode I associated with Hadley. I read or reread all her previous collections in preparation for a review of this, her fifth, for a review in the TLS, and I have to say: there would be no more pleasurable job that editing her Selected Stories – the collections all have some absolute bangers in them – though equally I’d be fascinated to see which ones she herself would pick.

Tomás Nevinson by Javier Marías, translated by Margaret Jull Costa. Not a top-notch Marías, but a solid one: Nevinson is a classic Marías sort-of-spook charged with tracking down and identifying a woman in a small Spanish town who might be a sleeper terrorist, from three possible targets, which naturally involves getting close to and even sleeping with them. I found some of the prose grating – flabbergastingly so for this writer (“we immediately began snogging and touching each other up” – I mean, come on!) – but the precision of the novel’s ethical architecture is absolutely characteristic.

Alone by Carlota Gurt, translated by Adrian Nathan West. A compelling and moving Catalunyan novel about the stupidity of thinking you can sort your life out by relocating to the country. Similar in theme to another book I read this year (Mattieu Simard’s The Country Will Bring Us No Peace) though I liked that one far less. I won’t say much about it as I read it without preconceptions and recommend it on the same terms. I will say it reminded me of The Detour by Gerbrand Bakker, which is another novel of solitude and the land, which again benefits from stepping into as into an unknown locality.

I am Homeless if This is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore. Oh boy. I love love love Moore at her best and though this aggravated as much as delighted me it’s been nagging me ever since I really want to go back and read again. [NB I have gone back to it, as my first book of 2024, and am being far less aggravated than on the first read). After a brisk, unexpected and exhilarating opening the novel seems to go into stasis, a slow series of disintegrating loops. It fails to do the thing that Moore usually seems to do quite effortlessly: keep you dizzily engaged with a cavalcade of daft gags and darkly sly sharper wit and observation. The protagonist, Finn, seems to miss what Moore usually gives her central characters: a dopey friend to dopily muddle through life with. He has a brother, Max, but he’s dying, and an ex, Lily, who, well… But all of this is done in flat dialogue wrestling with the big questions. Moore usually lets the big questions bubble up from under the tawdry minutiae of life (as, brilliantly, in A Gate at the Stairs); here, they’re front and centre. More tawdry minutiae, I say! I think part of my frustration with the novel comes from a place of ‘Creative Writing pedagogy’. Wouldn’t it be better, I think, to open up Finn’s character, show him as a teacher, his banter with the students, and his entanglement with the head’s wife? Rather than making all of that backstory, dumping it into reflection. The scene with Sigrid, for instance – her attempts to flirt with Finn – would be stronger if we’d already met her in the novel, already seen their relationship (such as it is) in action. You tell students, first you establish the ‘normal’ of the protagonist’s existence, then you throw it into confusion. So, am I giving LOORIE MOORE MA-level feedback? Well, yes. To which the response (beyond: “she’s LORRIE MOORE”) is: she’s not writing that kind of ‘normal’ novel. For every bit of LM brilliance (the gravestone reading “WELL, THAT WAS WEIRD”; the line “Death had improved her French”) there’s something off, that should or could be fixed or cut: the cat basket sliding around on the car backseat; the scene where Finn’s car spins off the road.

A Thread of Violence by Mark O’Connell. A suavely written book that digs into the true crime genre but stops short of the moral reckoning it at least flirts with: that in truth it shouldn’t exist – as a published book, at least. Will surely sit on reading lists of creative non-fiction in the future.

Tremor by Teju Cole. Read quickly and carefully (in physical not mental terms: it was bought as a Christmas present and sneakily read before being wrapped up and given ‘as new’), with the full intention of going back and reading it again. Cole is a literary intelligence for our times, that I’d drop into the Venn diagram of the contested term ‘autofiction’, not for its supposed relationship to the author’s life, but for its relation to the essay form.

Wish I Was Here by M. John Harrison. In fact I haven’t finished reading this. But I dug what I read, and will go back and finish it, but feel like I wasn’t in the right headspace for it at the time. It’s a book to sit with, to scribble on, to squint, to make work on the page. It’s not a book to do anything as basic as just read.

Sports and Social by Kevin Boniface. Stories from the master of quotidian observation that somehow avoids observational whimsy (the curse of stand-up comedy). If we build a new Voyager probe any time soon this should be on it, but failing that I’d recommend putting a copy in a shoebox and burying it in your garden, for future generations to find.

Thunderclap by Laura Cumming. A slight cheat, as I finished this on the first of January 2024. But it was a Christmas present and perfectly suited the slow, thoughtful last week of the ending year. I loved Cumming’s take on Dutch art, and how its thingness is often overlooked, and I loved the way she mixed together scraps of biography of Carel Fabritius (about whom little is known) and a memoir of her father (James Cumming, about whom little is known to me). The fragments hold each other in tension very well, but it’s not fragments for fragments’ sake. Cumming delineates a space for thinking about art, and its relationship to life, and lives, and other elements, big and small: death, sight-loss, colour-blindness, the nature of explosions, dreams, more. Tension’s not the word: it’s more like a provisional cosmology, that puts thematic and informational pieces in orbit around each other. There’s no symphonic tying-together at the end, but things are allowed back in, with new things too.

I only started underlining (in pencil: it’s a beautiful book!) towards the end. Here are some lines:

- “Open a door and the mind immediately seeks the window in the room”

- “Painting’s magnificent availability”

- Of an explosion witnessed first-hand: “a sudden nameless sound […] a strange pale rain”

There is so little known about Fabritius, with so many of his paintings lost, but really there’s so little known about any of us, the book suggests… and most of our paintings will be lost (as paintings by Cumming’s father have already been lost) but yet looking at art brings a special kind of knowledge, showing us “the intimate mind” of the artist, as of a novelist, or – as here – a writer. The love of art and of life shines through, or not shines, but diffuses, as in one of the grey Dutch skies Cummings writes about.

“But I have looked at art” she says, and she shares that looking (as does T. J. Clarke in his magnificent The Sight of Death) but she also opens up a space for looking. If “But I have looked at art” is an understatement, a compelling gesture of humility, then Cumming can also write, again towards the very end of the book, “What a glorious thing is humanity” and not have it jar, or smack of pomposity. There is much to cherish – much humanity (and what else is there in the world truly to cherish? – in Thunderclap.

Two books picked up and started on the days the author’s deaths were announced

Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy. Oh boy. Everything they say about it is true.

The Virgin in the Garden and Still Life by A. S. Byatt. I’d only previously read Possession, and some stories, and had both of these on my shelves. And what a joy they are! Byatt takes the Murdochian novel – the concatenation of sex and ideas produced by daft, intelligent, passionate people in a closed environment – and i) improves the plotting and ii) gives the prose a touch of the Jamesian-Bowenesque high church style, tightening a corset that Murdoch wears slack. These are novels characterised by a writer’s love for her characters: love meaning care and attention. Byatt’s narratorial control – knowing when to move between characters, how deep to dive into their experiences, and for how long – is excellent. She steps into the text, giving authorial asides and reflections that are just delightful. What in other writers can be a glib postmodern trick, here increases sympathy. That she treats her characters, at times, as literary constructions, somehow only binds you closer to them and their fates. The characters don’t just ‘follow an arc’, nor simply ‘change’, but actually grow— and there’s an intense pleasure to watching them grow, to being there in the paragraph when it happens. It’s a novel of characters, but also of ideas. The characters have them and discuss them, but also express them, and one is not allowed to outweigh the other. Byatt brings in Lawrence, Sartre, Kingsley Amis, and makes them work for their inclusion. (Amis gets a spanking.) And there are incidental pleasures: two characters swerving on their bikes and righting themselves, 200pp apart; the wonderful line from Mallarmé Tout exists pour aboutir à un livre; the inclusion, at the end of a chapter, of a personal favourite line of Shakespeare that made me gasp with thanks.

Older books I loved or particularly enjoyed

Old Masters by Thomas Bernhard. Joyously good, and actually quite moving at the end.

Septology by Jon Fosse, translated by Damion Searls. Loved the ‘slow’ prose style; loved the way the painting reoccurs; really didn’t like the ending. I feel like Fosse shortchanged me, out of fear of happiness.

The New Analog by Damon Krukowski. Full of insight into how we listen to (and make) music.

Capitalist Realism by Mark Fisher. Essential theory.

Go Went Gone by Jenny Erpenbeck. A thoughtful response to immigration, to the question of how we (and how novelists) might or should respond to global political issues.

Other notes:

I read War and Peace, and though there were moments of wonder I can’t say it was a highwater reading experience. I can’t see myself ever rereading it (as, for instance, I hope for Middlemarch, Ulysses, Proust, The Magic Mountain). I tried to re-read Gravity’s Rainbow, but ran into the sand. I’m not above reaching for guidance and support when tackling big or difficult books, but I couldn’t get the support or the headspace required for this, just now.

Full-ish list of books read in 2023 (r=reread)

- White Noise by Don DeLillo (r)

- Last Evenings on Earth by Roberto Bolaño (r)

- The Last Days of Roger Federer by Geoff Dyer

- Old Masters by Thomas Bernhard

- Septology by Jon Fosse, trans Damion Searls

- What it Means When a Man Falls From the Sky by Lesley Nneka Arimah

- The Informers by Bret Easton Ellis (r)

- How Music Got Free by Stephen Witt

- Trust Exercise by Susan Choi

- The Comfort of Strangers by Ian McEwan (r)

- Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line by Deepa Anappara

- Without Prejudice by Nicola Williams

- Kick the Latch by Kathryn Scanlan

- I Will Never See the World Again, by Ahmet Altan

- The New Analog by Damon Krukowski

- 20 Fragments of a Ravenous Youth by Xiaolu Guo

- Capitalist Realism by Mark Fisher

- The Waves by Virginia Woolf (r)

- The Pale King by David Foster Wallace

- Ten Planets by Yuri Herrera

- Tomás Nevinson by Javier Marías

- White Riot by Joe Thomas

- Granta Best of Young British Novelists 5

- Alone by Carlota Grut, translated by Adrian Nathan West

- Greek Lessons by Han Kang, trans Deborah Smith and Emily Yae Won

- The Past by Tessa Hadley

- Married Love by Tessa Hadley

- Sunstroke by Tessa Hadley (r)

- Bad Dreams by Tessa Hadley

- The Writing Life by Annie Dillard

- The London Train by Tessa Hadley

- Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy

- After the Funeral by Tessa Hadley

- From Far Around They Saw Us Burn by Alice Jolly

- I am Homeless if This is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore

- Pure Colour by Sheila Heti

- The Blush by Elizabeth Taylor

- The Hinge of a Metaphor, ed. Richard Skinner.

- Strangers at the Port by Lauren Aimee Curtis

- The Lark Ascending by Richard King

- In Praise of Shadows by Junichirō Tanizaki (r)

- Farthings by Charles Boyle

- Contempt by Alberto Moravia, trans. Angus Davidson

- History: A Novel by Elsa Morante, trans. William Weaver

- Monsters by Claire Dederer

- The Country Will Bring Us No Peace by Mattieu Simard, trans. Pablo Strauss

- Room Temperature by Nicholson Baker (r)

- Love Me Tender by Constance Debré, translated by Holly James

- Sports and Social by Kevin Boniface

- No. 91/92: notes on a Parisian commute by Lauren Elkin

- Own Sweet Time: A Diagnosis and Notes by Caroline Clark

- Foster by Clare Keegan

- Go Went Gone by Jenny Erpenbeck

- A Thread of Violence by Mark O’Connell

- Where Angels Fear to Tread by EM Forster

- A Little Give by Marina Benjamin

- The Virgin in the Garden by A. S. Byatt

- Still Life by A. S. Byatt

- A Sunday in Ville d’Avray by Dominique Barbéris, trans. John Cullen

- Company etc by Samuel Beckett.

- The Mask of Dimitrios by Eric Ambler

- War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy, trans. Anthony Briggs

- Job, The Story of a Simple Man by Joseph Roth

- Maigret’s Revolver by Georges Simenon

- Our Strangers by Lydia Davis

- Tremor by Teju Cole

- Edith’s Diary by Patricia Highsmith

- The Chapter by Nicholas Dames

- Thunderclap by Laura Cumming