Tagged: Samuel Beckett

Instead of June reading 2021: the fragmentary vs the one-paragraph text – Riviere, Hazzard, Offill, Lockwood, Ellmann, Markson, Énard etc etc

This isn’t really going to function as a ‘What I read this month’ post, in part because I haven’t read many books right through. (Lots of scattered reading as preparation for next academic year. Lots of fragmentary DeLillo for an academic chapter I filed today, yay!)

Instead I’m going to focus on a couple of the books I read this month, and others like them: Weather by Jenny Offill, and Dead Souls, by Sam Riviere. I wrote about the fragmentary nature of Offill’s writing last month, when I reread her Dept. of Speculation after reading Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This (the month before), all three books written or at least presented in isolated paragraphs, with often no great through-flow of narrative or logic to carry you from paragraph to paragraph.

Riviere’s novel, by contrast, is written in a single 300-page paragraph, albeit in carefully constructed and easy-to-parse sentences. And, as it happens, I’ve just picked up another new novel written in a single paragraph – this one in fact in a single sentence: Lorem Ipsum by Oli Hazzard. I haven’t finished it, but it helped focus some thoughts that I’ll try to get down now. These will be rough, and provisional.

Questions (not yet all answered):

- What does it mean to present a text as isolated paragraphs, or as one unbroken paragraph?

- Is it coincidence that these various books turned up at the same time?

- Does it tell us something about ambitions or intentions of writers just now?

- Are fragmentary and single-par forms in fact opposite, and pulling in different directions?

- If they are, does that signify a move away from the centre ground? If not, what joins them?

Let’s pull together the examples that spring to mind, or from my shelves:

Recent fragmentary narratives:

- No One is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood (2021)

- Weather (2020) and Dept. of Speculation (2014) by Jenny Offill

- Assembly by Natasha Brown (2021) – in part, it jumps around, I haven’t read much of it yet.

And further back;

- This is the Place to Be by Lara Pawson (2016) A brilliant memoir written in block paragraphs, but allowing for a certain ‘through-flow’ of idea and argument.

- This is Memorial Device by David Keenan (2017) – normal-length (mostly longish) paragraphs, but separated by line breaks, rather than indented.

- Satin Island by Tom McCarthy (2015) – a series of long-ish numbered paragraphs, separated by line breaks.

- Unmastered by Katherine Angel (2012) – fragmentary aphoristic non-fiction, not strictly speaking narrative.

- Various late novels by David Markson, from Wittgenstein’s Mistress onwards

- Tristano by Nanni Balestrini (1966 and 2014) – a novel of fragmentary identically-sized paragraphs, randomly ordered, two to a page. The paragraphs are separated by line breaks, but my guess is that the randomness drives the presentation on the page.

Recent all-in-one-paragraph narratives:

- Lorem Ipsum by Oli Hazzard (2021)

- Dead Souls by Sam Riviere (2021)

- Ducks, Newburyport by Lucy Ellmann (2019)

And further back:

- Zone (2008) and Compass (2015) by Mathias Énard

- Various novels by László Krasznahorkai, of which I’ve only read Satantango (1985) – a series of single-paragraph chapters.

- Various novels by Thomas Bernhard, of which I’ve only read Correction (1975) and Concrete (1982)

- The first chapter of Beckett’s Molloy (1950) is a single paragraph, as is the last nine tenths of The Unnameable(1952)

- The final section of Ulysses, by James Joyce (1922)

So, my thoughts:

Continue readingFebruary Reading: Proust, Beckett

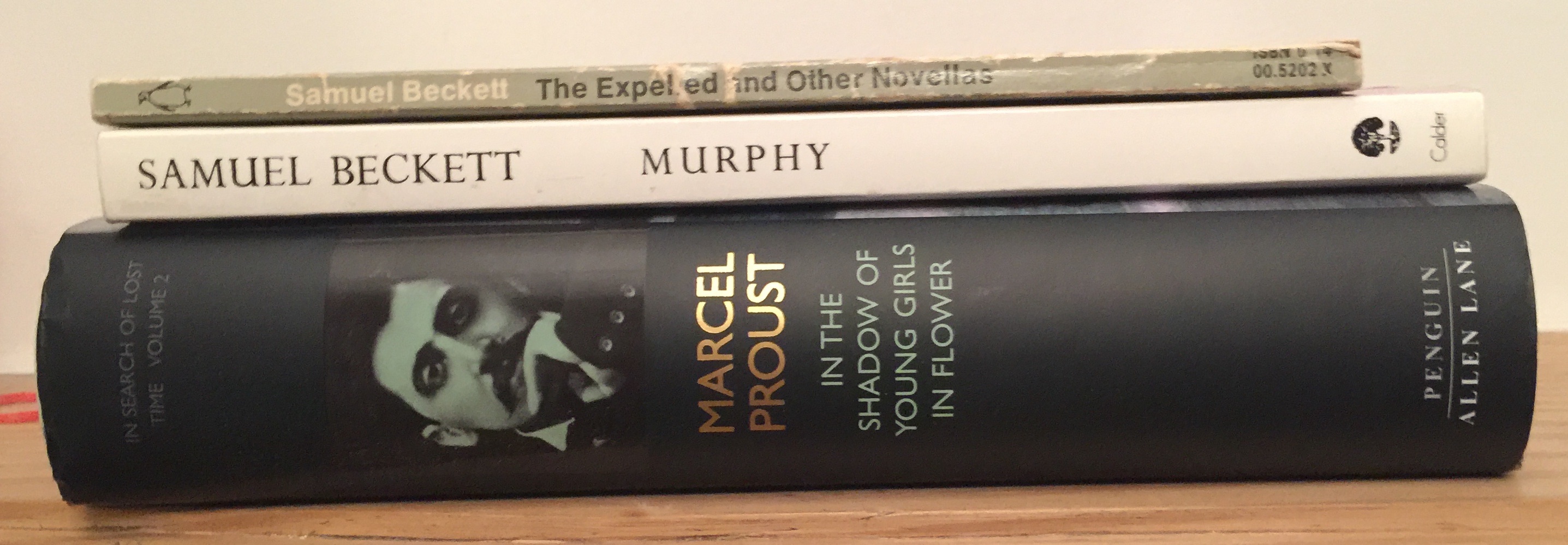

I finished In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower a couple of days into March, this being the second volume of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, in the translation by James Grieve, which means I’m not quite reading a book a month. I’m also reading not much else. As I said in last month’s post, reading Proust at any time, but especially at bedtime, is slow going. Picking up an Iris Murdoch novel – I’m trying to tick another one or two off before taking part in a panel discussion at the Cambridge Literary Festival next month – I find that I zip through double or even triple the number of pages.

I finished In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower a couple of days into March, this being the second volume of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, in the translation by James Grieve, which means I’m not quite reading a book a month. I’m also reading not much else. As I said in last month’s post, reading Proust at any time, but especially at bedtime, is slow going. Picking up an Iris Murdoch novel – I’m trying to tick another one or two off before taking part in a panel discussion at the Cambridge Literary Festival next month – I find that I zip through double or even triple the number of pages.

The other books in the photograph are by Samuel Beckett, whose abstruse essay on Proust I’ve been glancing at at work, more in hope of the odd brief flint-like spark of understanding than of any general illumination. I turned to ‘The End’, collected with ‘The Expelled’ and other “novellas”, following the introduction to this story by Daragh McCausland in his Personal Anthology. (If you don’t know this online project, run by me, then check it out here.)

Daragh called it “a masterpiece”, and I’m afraid it didn’t seem so to me. Perhaps I read it too quickly, but I found it unrewarding, dark and constipated, and not shot through with any lyricism to speak of. Which is not to contradict Daragh, who wrote wonderfully about Beckett’s favourite short fiction, but to note my unsureness when it comes to this writer.

The late, spare stuff – the bleached bones of thought – is great, but can scarcely be read: like koans, they are there to be looked at and contemplated, not imbibed and processed as we do with most prose. And the “early, funny” stuff is great in its own way, if you ignore Beckett’s self-immolating hermeneutic diversions, the bonfires he makes of his own intellectual vanity. But ‘The End’ seems to me to fall between those two stools. He has sloughed off the early, conflicted attempts at connecting with the reader, and is telling stories of disconnection instead, but hasn’t yet built that rejection into the form of the writing.

So I turned to Murphy, right in the middle of my Proust, wondering if I would still get from this what I have done in the past. It was a quick check-in: is this still good? Do I still get it?

(This is a permanent aspect of reading that doesn’t show up in these blog posts. We’re always glancing into previously read work, as well as those unread, those come newly into the house. This month, for instance, I read a few pages of the Patrick Melrose novels, after watching the first episode of the Cumberbatch-starring adaptation, which was very good, if you ask me. The novels, of course, are splendid, already part of the literary landscape, with a status of their own quite disconnected from their author. I must re-read them, I think, leaving the book on a surface, where it sits for days or weeks before being reluctantly reshelved.)

(February also featured a certain amount of reading for the Galley Beggar Short Story Prize, about which I hope to write another blog post.)

So Murphy. I picked it up to check, then thought: I can read this, now, if I read it quickly. It’s a book to go through you like a dose of salts. It is perhaps the prose work by Beckett that most taunts the reader with the idea of what he could have produced, had he been of a more amenable disposition, had he accepted the role of writer as, among other things, entertainer. Continue reading

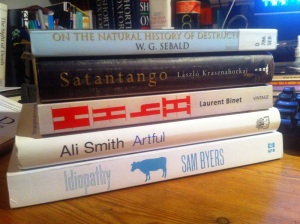

November reading: Krasznahorkai, Binet, Byers

Reading Lászlo Krasznahorkai’s Satantango was a struggle. I wish it hadn’t been, and I’m the first to argue for the improving qualities of difficult books, but this was one that I persevered with in the face of a dwindling conviction that I was going to be able to make any sense of it.

I picked it up largely out of respect for the names on the cover and title page – admiring quotes from WG Sebald (who has loomed large in my reading this year) and Susan Sontag, and the added interest of reading the translation of George Szirtes, lest we forget he is significantly more substantial a literary presence than his marvellous Twitter feed.

I knew nothing about the author, nothing about the book, and took the opportunity to add nothing to this sum before reading – as someone pointed out about the Olympic opening ceremony, the opportunity to sit down to a cultural experience with absolutely no preconceptions is a rare one. Nor have I read anything about the book since finishing it, which I am tempted to do now, in part to see what it is I missed. For a lot of its incredibly dense 270 pages I was trying, trying so hard, to find meaning, discern allegory, pick out the thread or symbol or standpoint that would allow me to take a view on the book as a whole.

I knew nothing about the author, nothing about the book, and took the opportunity to add nothing to this sum before reading – as someone pointed out about the Olympic opening ceremony, the opportunity to sit down to a cultural experience with absolutely no preconceptions is a rare one. Nor have I read anything about the book since finishing it, which I am tempted to do now, in part to see what it is I missed. For a lot of its incredibly dense 270 pages I was trying, trying so hard, to find meaning, discern allegory, pick out the thread or symbol or standpoint that would allow me to take a view on the book as a whole.

Forgive the clumsy phrasing, but never has there been a book so impossible to read between the lines of. Continue reading

July reading: Blackburn, Ridgway

Some months go by and you look at the list of books you’ve read and wonder: how so short? How can I have read so little? The reasons are often dull, though sometimes they do come down to a lack of engagement with the books to hand, sometimes a lack of engagement with the idea itself of reading, or perhaps the idea of reading novels.

After finishing Keith Ridgway’s Hawthorn & Child (which I’ll get to below) I picked up and put down Christoph Simon’s Zbinden’s Progress (didn’t grab me at all), Richard Beard’s Lazarus is Dead (oh, I thought, after reading less than two pages, it’s Joseph Heller’s God Knows) and Thierry Jonquet’s Tarantula (as recommended by a detective in Houellebecq’s The Map and the Territory… but, my god, the translation is appalling, and the “story of obsession and desire, or power and revenge” more or less the level of any other Sade knock-off). Perhaps I’m jaded. Perhaps I’m read out. Perhaps I’m waiting for August, and the chance to leave London and sit outside a tent or by a pool and really get into a ‘big’, ‘proper’ novel. Continue reading

After finishing Keith Ridgway’s Hawthorn & Child (which I’ll get to below) I picked up and put down Christoph Simon’s Zbinden’s Progress (didn’t grab me at all), Richard Beard’s Lazarus is Dead (oh, I thought, after reading less than two pages, it’s Joseph Heller’s God Knows) and Thierry Jonquet’s Tarantula (as recommended by a detective in Houellebecq’s The Map and the Territory… but, my god, the translation is appalling, and the “story of obsession and desire, or power and revenge” more or less the level of any other Sade knock-off). Perhaps I’m jaded. Perhaps I’m read out. Perhaps I’m waiting for August, and the chance to leave London and sit outside a tent or by a pool and really get into a ‘big’, ‘proper’ novel. Continue reading