Tagged: Elizabeth Bowen

‘After my own heart’: an occasional post after Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence

I was reading Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence last night, in the way that you’re supposed to, dipping into it, looking for something to snag my interest – either the writer of the sentence in question, or the sentence itself, or something Dillon might have to say – and I alighted on his section on Elizabeth Bowen, whose stories I also happen to haphazardly reading at the moment, because I’m reading Tessa Hadley’s stories, Hadley being a fan and literary descendent of sorts of Bowen… and, anyway, I read this passage:

As I write, I’m two thirds of the way through A Time in Rome, which [Bowen] published in 1960, and I think I have found, again, a writer after my own heart. How many times does it happen, dare it happen, in a life of reading? A dozen, maybe? There is a difference between the writers you can read and admire all your life, and the others, the voices for whom you feel some more intimate affinity. Could Elizabeth Bowen be turning swiftly into one of the latter, on account of her amazing sentences?

Which is marvellous, and sparked two particular thoughts, last night, and has sparked a couple more, this morning, as I sit down to write, on a Bank Holiday Sunday morning, at just gone 8am. There’s one, on the phrase “after my own heart”, that I really want to get to, so I’ll try to dispatch the other ones briefly.

Firstly, the word ‘affinity’, which is obviously an important word for Dillon: it was the name of Dillon’s next book, after all. It could just as easily have been the title of this one. What interests me about the word, however, is its aura of neutrality. When we think of the connections that get built between – as here – us as individual readers, and particular writers, we tend to look to one or the other as the active agent in the relationship. Either the writer is a genius – they seduce me, impress or overawe me – or I love the writer, I find something particular in them. But an affinity is bipartisan, and objective, as if unwilled by either. The chemical usage of the word is the most critically productive one, especially after Goethe applied it to human relationships in Elective Affinities, but in fact the original meaning was to do with relationships – in particular relationships not linked by blood, such as marriage, or god-parentship. I suppose, contra Goethe, what I like about the term is that these affinities that Dillon is talking about seem to be un- or non-elective, but weirdly, inexorably fated.

(NB I haven’t read Affinities yet, so maybe Dillon goes into all this in his book.)

The other brief thought from this morning was that, although Dillon does talk about Bowen’s fiction in his piece on her, the sentence he picks to write about is from her sort-of-travel book A Time in Rome. And this made me think of the death, last week, of Martin Amis, and how much of the online critical chat had an undercurrent of favouring the non-fiction (the journalism, and the first memoir) over the fiction (with a few exceptions, usually involving Money), and I wondered if anyone had really considered, at length, the legacy of writers that had written both fiction and non-fiction, and what it meant when one was favoured over the other. Susan Sontag wanted to be remembered as a novelist, but isn’t, and won’t be. It would surely appal Amis if he felt that it was his book reviews and interviews that we remembered him for. Geoff Dyer does talk about this a bit with reference to Lawrence in Out of Sheer Rage, but I’d like to read something broader. If a writer has a style, and that style is to an extent consistent over their fiction and non-fiction, then what are the conditions by which they become remembered, and stay read, after their death, for one rather than the other? Or, alternatively, is there a difference in terms of how a similar style applies to fiction, and non-fiction?

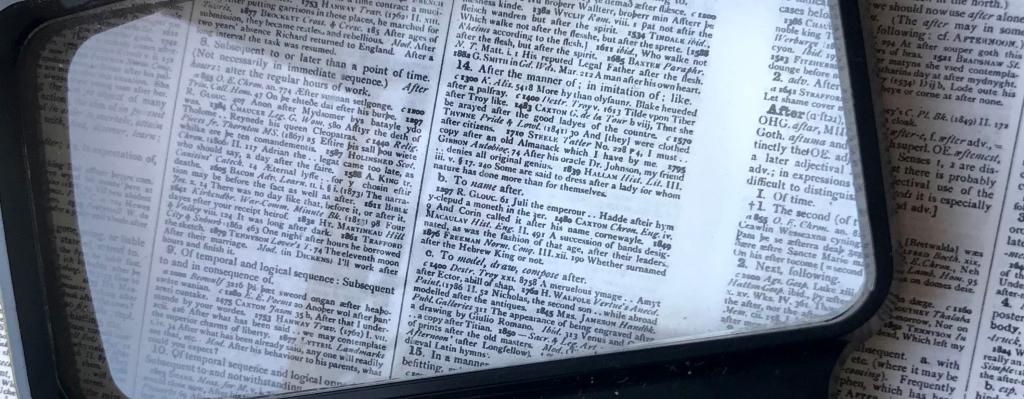

Now to the original point I wanted to make. Dillon’s paragraph on his relationship to Bowen is lovely, and I’m sure many readers will relate to it, as I did, but I was particularly struck by the phrase a writer after my own heart. “After my own heart” – it’s a strange and wonderful idiom, and sent me – it’s a Bank Holiday weekend – to the dictionary. ‘After’, after all, is a preposition that, like most prepositions, has a variety of different uses.

“After my own heart” could, for instance, have a sinister intent, as with hounds after a fox. The writer in pursuit of the reader’s heart. But it doesn’t mean that. It means “after the nature of; according to”, a usage going back to the Bible (“There is therefore now no condemnation to them which are in Christ Jesus, who walk not after the flesh, but after the Spirit”, Romans 8:1-2) – though the specific usage of “a man after his own heart” isn’t recorded until 1882, when it appears in, of all places, The Guardian, attributed to one G. Smith.

But the other meanings or uses of ‘after’ hover around the word. ‘After’, too, in the sense of “after the manner of; in imitation of”, as it’s used in art history – for example, Picasso’s The Maids of Honor (Las Meninas, after Velázquez). I remember a novel called After Breathless, by Jennifer Potter, that I read simply because it was inspired by A Bout de Souffle, my favourite film. “After my own heart” as critical interrogation.

And then the word ‘own’ in the phrase, too: after my own heart. It’s a phrase that is deeply, reverberantly embedded in the language from which it grows. It’s a phrase to conjure with. It’s an idiom, in other words.

My final brief thought, and again someone has probably written on this, but what exactly is the relationship between idiom and cliché? Does an idiom have to pass through the state of being a cliché before it can achieve this linguistic apotheosis? Is an idiom merely a cliché that has freed itself of the negative connotations of overuse – overuse with a single meaning – to allow itself to take on other meanings. Because that’s the problem with clichés, isn’t it? Not that they’re overfamiliar as phrases – as signifiers – but because their overuse has obliterated the meaning the phrase intends. The site of meaning has been rubbed raw.

A fresh vision of hell, the old dead scanning the new

First, read this:

Euston. All the way down the train doors burst open while the inky ribbon of platform still slipped by. Nobody could wait for the train to stop; everybody was hurling themselves on London as though they, too, must act upon some inhuman resolution before it died down. She, now it came to the point, was to be the last to leave the carriage; she stopped to stare at herself, as thought for the last time, in the mirror panel over the seat. Picking up her suitcase, stepping out onto the platform, she looked from left to right, then began to walk along the flank of the train. The few blued lights of the station just showed the vaultings up into gloom; toppling trolleys cut through the people heaving, thrusting, tripping, peering. Recognition of anybody by anybody else seemed hopeless – those hoping to be met, hoping to be claimed, thrust hats back and turned up faces drowningly. Arrival of shades in Hades, the new dead scanned dubiously by the older, she thought she could have thought; but she felt nothing – till her heart missed a beat, her being filled like an empty lock: with a shock of love she saw Robert’s tall turning head.

It is from Elizabeth Bowen’s The Heat of the Day, the first book of hers I’ve read, and one that I wrote about here. A struggle at times, I’ll admit, in its density – aptly exemplified by the paragraph above – but shot through with writing of such luxurious intelligence that it made scanning your average contemporary novel feel like drinking dishwater.

Let me pull the line out for you, that in particular struck me:

Arrival of shades in Hades, the new dead scanned dubiously by the older

Now, firstly, this may be an idea, or an image, that has appeared elsewhere before this. (I haven’t read Dante through even to the end of Hell, for example.) But certainly it is a pointedly modern twist on traditional conceptions of damnation.

Hell here is not the flame-grilling of old time religion, nor the more existential crisis of definitive knowledge of one’s banishment from God; no, here it is simply the boredom of transit, become torment through extension ad infinitum.

Bowen’s novel is set during the Second World War, when air travel was not yet common, but still it’s easy enough to transpose the scene from railway station to airport. Easy enough, but still there is some elucidation needed. The damned, here, are in Arrivals, whereas we all know that it’s the Departures Lounge that most equates to our contemporary idea of purgatory: an unliveable public/private space that is merely the physical manifestation of dead time; designed only to keep us from the Paradise of our holiday destination; comprehensively fitted out with worthless and useless distractions; and peopled with hordes of people just like us whom we hate by virtue of their showing, objectively and unanswerably, quite how bored and badly behaved we, too, are.

So we’ve got to somehow merge those two places, Destinations and Arrivals. The boredom of Departures, plus the disappointment of Arrivals. The moment of arriving in Hell is one in which the passage from the plane, via Customs and Immigration, and leading to that first glimpse of the Arrivals lounge, with people leaning on the angled metal barriers, some of them holding up cardboard signs or clipboards with names on… but the realisation that we are not about to be released and set loose into the free but dirty post-plane world of holiday or home, but that we will never leave, that our arrival is into another Departure Lounge, but one from which we will never depart for anywhere…

…and in which the only entertainment is watching the newcomers arrive – perhaps we make the trip especially to meet those we loved, back on earth – and to see their expressions drop from anticipation, through realisation, to despair.

Thank you, Elizabeth Bowen.

Gone in the blink of an eye: Elizabeth Bowen’s contingent realism

I’m reading Elizabeth Bowen for the first time and finding it a slow-going but exhilarating experience – perhaps the closest comparison, in terms of necessary application to the page, is Javier Marías, someone else who won’t be rushed, whose paragraphs flow like dark syrup, not clear water.

One of the things that has most struck me – and that is very different from Marías – is the utter contingency of Bowen’s descriptions. Things are always shown in the light of the moment, not with any definiteness; so much so that you’d almost think that, were you to glance away from the page, and back again, the words on it would have changed, with the movement of a cloud across the sun, or the bough of a tree across a window.

As such, she is working very much against received ideas of ‘realism’ in prose writing, against what Henry James called “solidity of specification”. There is no solidity here; everything is always on the point of dissolution – and this sense of unreality is surely no accident; Bowen extends it to her characters:

The sun had been going down while tea had been going on, its chemically yellowing light intensifying the boundary trees. Reflections, cast across the lawn into the lounge, gave the glossy thinness of celluloid to indoor shadow. Stella pressed her thumb against the edge of the table to assure herself this was a moment she was living through – as in the moment before a faint she seemed to be looking at everything down a darkening telescope. Having brought the scene back again into focus by staring at window-reflections in the glaze of the teapot, she dared look again at Robert, seated across the table, between his nephew and niece.

Obviously the syntax is a brake on understanding; Bowen seems fusty and old-fashioned in her sentences, leaping back over Virginia Woolf towards the likes of James, even when what is being broached in those sentences – the sheer ephemerality of self-consciousness – is as modern as anything by Woolf. Stella (the main character of The Heat of the Day) has to steady herself by looking at the reflections of the windows caught in the glaze of the teapot before she can dare to look at her lover. Why ‘dare’? Well, because she’s scared that when she looks for him, where he was sitting only a moment before, he will have disappeared, sparked out of existence. Continue reading