Occasional review: on finishing A.S. Byatt’s ‘Frederica quartet’: The Virgin in the Garden, Still Life, Babel Tower, A Whispering Woman

A. S. Byatt died on 16 November 2023 and the next day, when her death was announced, I took down The Virgin in the Garden from the shelf, where it had sat unread for I don’t know how long, and began to read it. I’d previously only read Possession by her, plus some short stories, which I’d liked well enough, but this I enjoyed far more. So much so that I went straight from The Virgin in the Garden to the second novel in ‘the Frederica Quartet’, Still Life, as I already had that to hand, but then paused for a couple of months before reading Babel Tower and then had another pause before A Whistling Woman, which I finished at the start of April 2024. I thoroughly enjoyed the whole of the quartet, and found parts of it absolutely thrilling, intellectually and on occasion emotionally. These are novels of ideas, and ambition, but are also threaded through by a writer’s love for her characters: love here meaning care and attention, or attentiveness.

These books get called ‘The Frederica Quartet’ because they follow the life and intellectual development of one central character, Frederica Potter. Frederica is 17 at the start of the first book, which is set in the year of Elizabeth II’s coronation, 1953, and she’s in her mid 30s at the end of the last book, in 1970 – in fact in historical terms she’s an exact contemporary of Byatt. The books do expand their concerns beyond Frederica, sometimes far beyond, and sometimes too far. To start with we spend as much time with her parents, the domineering Bill and emollient Winifred, and her siblings – elder sister Stephanie and younger brother Marcus – and also with Alexander, the older man with whom the teenaged Frederica is infatuated. In later books this diffuseness of focus increases, such that at times Frederica seems almost tangential. This isn’t necessarily a good thing, especially – cough – if you are in love with Frederica, as it’s possible to be in love with, for instance, As You Like It‘s Rosalind. Byatt says in an interview: “It isn’t Frederica’s book – though she’s the sort of person who would muscle in and try to take it!”

These notes draw on and develop the comments in my 2023 and 2024 Reading threads on Bluesky.

My first point, looking back on the quartet, is the oddity that the period covered by the novels is shorter – at 17 years – than the period over which they were published: 24 years. In other words the novels became more historical as the period they covered receded – and the novels in part are realist depictions of a specific period in English social and cultural history, a thrusting and exciting period that saw the rise of television and the new universities, and of the counter-culture of the 1960s.

As a series of books these are less programmatically ‘historical’ or ‘historical-thematic’ than, say, the Rabbit tetralogy, or A Dance to the Music of Time. (As a side note, and based on my distant memory of reading Powell’s twelve-novel sequence, the treatment of the anarchic-religious commune in Byatt’s A Whistling Woman is rather similar to the Harmony cult in Hearing Secret Harmonies.) The treatment of early BBC Two-style television is great – all Jonathan Miller and ‘Alice in Wonderland’ – but the attempts at creating a Bowie-esque pop star fall flat. Byatt can do many things, but she can’t do rock. Occasional historical events are mentioned in passing, but Byatt is more interested in the intellectual and spiritual tenor of the times than their politics, in blunt terms.

Here are the dates of the novels:

- The Virgin in the Garden: published 1978; set 1953.

- Still Life: published 1985; set 1953-1956

- Babel Tower: published 1996; set 1964-1967

- A Whistling Woman: published 2002; set 1968-1970.

Part of the gap between the second and third novel was, Byatt has said, caused by the death of her son, killed aged 11 by a drunk driver. She also delayed writing Babel Tower to write Possession, which apparently seemed like it would be more fun to write. It was – and it was also a massive commercial success, winning her the Booker Prize in 1990. Which doubtless also delayed things.

The books are hugely ambitious. They want to give a picture of England in London and Yorkshire over this period of accelerated upheaval, but they also offer the pleasures of a family saga (how does parenting affect children? how do siblings get along? who will Frederica sleep with, and why?), and they are full to brimming of the ideas that the characters are having: about science, art, sex, psychology, religion, education, literature. The ideas are built into arguments, in conversations and letters, but also in the characters’ thoughts, thanks to Byatt’s brilliant use of omniscient narration. That said, I agree with Ruth Bernard Yeazell’s balanced LRB review of A Whispering Woman, in which she says:

“it’s possible to feel that the Potter novels occasionally suffer from an overindulgence of their author’s cognitive appetites. In a recent interview, Byatt credited Proust with having taught her that one could ‘put everything into’ a novel, but A la recherche du temps perdu may not be the safest model in this respect; and of course much depends on how ‘everything’ is reimagined and articulated. The problem is not that Babel Tower or A Whistling Woman ‘smells of the lamp’, as Henry James famously complained of Eliot’s historical scholarship in Romola, but that the proliferation of vocabularies and allusions – not to mention the sheer number of characters, many of them introduced in previous volumes – sometimes threatens to bury the narrative rather than illuminate it.”

By the way, do NOT so much as glance at any more of Yeazell’s review before reading the books if you want to avoid major spoilers!

Although Byatt said she was responding to D. H. Lawrence and George Eliot in writing the books, my original response to The Virgin in the Garden was that:

she takes the Murdochian novel – the concatenation of sex and ideas produced by daft, intelligent, passionate people in a closed environment – and i) improves the plotting and ii) gives the prose a touch of the Jamesian-Bowenesque high church style, tightening a corset that Murdoch wears slack.

It’s good to see the omniscient narrator done well, when it’s currently so out of fashion. Byatt makes it work at a domestic level – the smooth passage between different characters’ POVs in the Potters’ kitchen – but she’s also up for orchestrating major set pieces, of which there are many, with aplomb.

Here’s Byatt, in that same interview, talking of George Eliot:

“Sometimes she says, ‘He thought,’ and sometimes she almost suggests that she doesn’t quite know what somebody thought, but that it was a bit like this. She can do all those things, because she’s got a flexible instrument.”

She also does the interesting thing of starting (after the prologue) with a central character (Alexander) who is not there at the end. His emotional arc drives the plot of the first book, but is not absolutely central to the thematic concerns of the novel. And in fact the intricate plotting of a love affair or mutual seduction involving this 34-year-old male teacher and Frederica’s wilful, self-possessed 17-year-old schoolgirl (he’s not her teacher, if that makes it any less reprehensible) is very carefully negotiated – were things different then? you wonder, in anguish – and it pays off in a way I could only applaud with my hands over my eyes, as it were.

Although the plotting of the first book is tight, this loosens as the quartet goes on. In part this is to let all the ideas in, and all the characters – the long cast list is important for the novel’s realism, so that Byatt can move up and down the country and through British society without making the world of the book too compressed and coincidence-prone. Because of this some of the secondary characters become rather easy to muddle up – or easy, in fact, to give up on identifying at all. Sometimes re-encountering, say, a Monica Thone, or Geoffrey Parry or Thomas Poole late in one of the novels is a bit like seeing someone coming towards you across the room at a party, when you think, I know you, I know I know you, but who the hell are you again?

Byatt is also generous and catholic in her use of different literary modes (or ‘instruments’, to her use term). The third and fourth books include extended passages from two different novels-within-novels, and the fourth book has long epistolary sections, with Babel Tower also including legal transcripts and four very funny ‘reader reports’ that Frederica writes on books from a small publisher’s slush pile. When Frederica gets divorced we don’t just get the legal letters; we also get Frederica’s angry Burroughs-style cut-ups of those same legal letters. Her legal deposition for the divorce is seen first as her anguished scribbled notes and then in impersonal legalese.

These postmodern techniques are mostly there for a reason, and they build and echo the novels’ themes in a variety of ways. Byatt gives a spoken cameo to Anthony Burgess (no longer alive at time of publication) and mentions in her acknowledgements ‘borrowing’ an Iris Murdoch character – who, I wonder. I was less taken with the increasingly silly character names. You can roll your eyes at an ambitious academic called Gerard Wijnnobel – ha and indeed ha – but the likes of Hodder Pinsky, Elvet Gander, Kieran Quarrell and Avram Snitkin – all from A Whispering Woman – pile up with no real sense of who they actually might be, let alone why they’re called that.

Byatt also chops and changes her structural approach to the books.

- The Virgin in the Garden has 44 named and numbered chapters across three sections, plus a proleptic (flash-forward) prologue to 1968.

- Still Life likewise has 33 named and numbered chapters, though not split into sections, and a proleptic prologue that actually hopfrogs the entirety of the quartet’s chronology to land us in 1980!

- The last two books are simpler, which is perhaps a shame. Babel Tower has 21 numbered but un-named chapters, and no sections, and a one-page prologue that is more epigraph than scene.

- A Whistling Woman has 27 chapters, again unnumbered, again not in sections and this time with no prologue at all.

The sense I hope this gives is that Byatt is not programmatic about her books. They change their approach in line with her developing skills and intentions as a novelist. At times it seems like she’s improvising, as a concert pianist might improvise – or she’s like Glenn Gould or Keith Jarrett, humming along with her keyboard work.

An example here from the romance between Alexander and schoolgirl Frederica in The Virgin in the Garden, when Frederica says to him: “Just hold me a little. Without obligation.”

“He lifted her down into his swelling lap, and held her. They sat very still. In the forest of his mind the undergrowth crashed furiously; he was in a car rushing down a steep slope, careering out of control. He screamed shrilly and silently, in his head, with vertiginous pleasure like the child he had been on the Big Dipper, and the relentless literary tic-tac told him, not out of his childhood but sighing in German accent out of The Waste Land, to hold on tight, there were no clean or private phrases, but it didn’t matter, there were no doubt no private or star-separate schoolgirls to hold on your knee, if the truth were known. And Lolita still unwritten.”

That ‘furiously crashing undergrowth’ is very good; the paragraph gets a bit out of control after that; but the narratorial aside that Byatt gives us – for, yes, her novel is set in 1953, and Lolita was published in 1955 – is as dry as the driest sherry.

Or there’s the passage, from most of the way through Still Life, when Byatt turns confidingly to the reader and says:

“I had the idea, when I began this novel, that it would be a novel of naming and accuracy. I wanted to write a novel as Williams said a poem should be: no ideas but in things. I even thought of trying to write without figures of speech, but had to give up that plan, quite early.”

She then develops her comment into a short disquisition on metaphor, which includes this wonderful apercu, one that hit home with the force of an aphorism, something I feel and think, but have never seen so well articulated:

“Frederica’s friends would have pounced on Marcus’s history and the cleistogamous flower and thought they had understood something because they had seen an analogy.” (my italics)

These breakings of the fourth wall, that in other writers can be a glib trick, somehow seem to increase sympathy. It’s like a gentle welling up of a bubble of writerly thought, or even compassion, that just as easily subsides or pops and is gone. That she treats her characters, at times, as literary constructions, somehow only binds you closer to them and their fates.

This, I suppose, is Byatt’s triumph: that she embraces and subscribes to ‘literary realism’ (the characters are real; we are invested in them; we care about them and laugh and cry with their joys and despairs) but at times she also stands above it and sets it aside – but, importantly, without ever definitively undermining or disavowing it, destroying it or expelling it from the garden of her prose.

The second book, Still Life, is probably the best in purely literary terms. Byatt’s narratorial control – knowing when to move between characters, how deep to dive into their experiences, and for how long – is instinctual, and expert. Frederica is grown up from the impetuous schoolgirl, and the novel seems to have grown up too. Her elder sister, Stephanie, continues to take the novel in other directions. Their younger brother, Marcus, is treated much better than in The Virgin in the Garden – in the first book he had a kind of mental disorder by which he solved maths problems by ‘seeing’ them physically in a mental ‘garden’. This makes him a prodigy, and opens him to exploitation, and it’s all a little opaque and icky, to me at least.

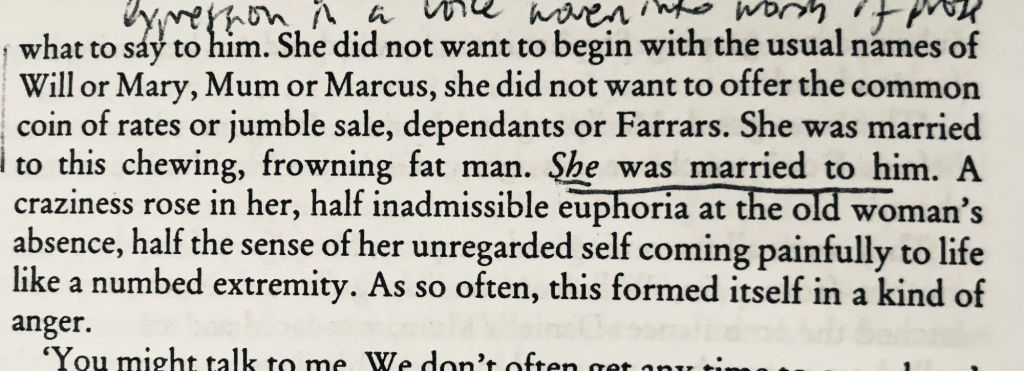

Here’s an example of Byatt’s ability to get down in prose not just the essence of a character (their quiddity) but the force of that essence, and also their own sense of that strength of their self. In this paragraph it’s done simply in the use of the italics.

SHE was married to him! (This is Stephanie, thinking about her husband Daniel, and Daniel’s awful mother, who’s staying with them.) Still Life is anything but still: it’s immensely vital, and immensely moving.

Babel Tower is a different proposition: nearly twice the length of Still Life and overstuffed with ideas, as if the gap between the two novels had given Byatt too much that she needed to say. It is carried along by its vigour, the breadth of its interest, and the cleverness of its postmodern antics (some of which I listed above), as well as the emotional maelstrom of the central plot strand, which is Frederica’s terrible marriage, and her attempts to extricate herself and her son from it.

The final book, A Whistling Woman, was my least favourite of the four, by virtue of its lack of force, in terms of plot; and its lack of originality, in structural and thematic terms. The treatment of Frederica’s career in TV is well done, and it was nice to see more of the University of North Yorkshire, but the theme of 1960s counter-culture she explores through the radical ‘anti-university’ seems a retread of the art school sections of Babel Tower. Byatt’s cast of characters has expanded, and it’s nice to see old faces reappear, but I was angry to see Frederica’s parents, and the wonderful Daniel Orton, just float by in the slipstream, with occasional cameo appearances. They’re great characters, and I wanted more of them.

It seems odd that Byatt didn’t go for a stronger conclusion to the quartet as a whole. It doesn’t seem that she was planning more books. As a book A Whistling Woman is well enough constructed. Its twin plots are wrapped up effectively, with a conference at the North Yorkshire University, and a hippie-religious cult that springs up across the moor from it – but neither of these really involve Frederica. And there is a lovely late echo of the start of the quartet, with a production of The Winter’s Tale that mirrors the first book’s Elizabeth play – but again this is not really about Frederica, and is mood music, rather than set piece.

Frederica’s personal-emotional ‘resolution’, when we get it, is neat, and cute, but has a real ‘to-be-continued’ vibe about it. There’s no reason, you think, that our access to her story should end here. It points onwards, to continued life, and also almost frustrates with its happy ending – though see below for a typically apposite comment on that expectation.

Certainly, the quartet as a whole has been a fantastic reading experience, and I enjoyed A Whistling Woman for letting me spend more time with the wonderful Frederica, but it’s missing the literary ingenuity that Byatt sprinkled through the other books, the ‘top of the head removal’ moments of connection and illumination.

I’ll finish with a lovely bit from Bill Potter, Frederica’s dad, talking about The Winter’s Tale, near the end of A Whistling Woman:

“The human need to be mocked with art – you can have a happy ending, precisely because you know in life they don’t happen; when you are old, you have a right to the irony of a happy ending – because you don’t believe it.”

Lovely write up. I also returned to Byatt this year, after only having read Possession previously (probably about twenty years ago). I read The Game — quite an early one I think — and thoroughly enjoyed it, despite it also containing some of the quirks you mention above.

I’m looking forward to exploring more and the quartet sounds like it might be a good place to start!