Tagged: Javier Marias

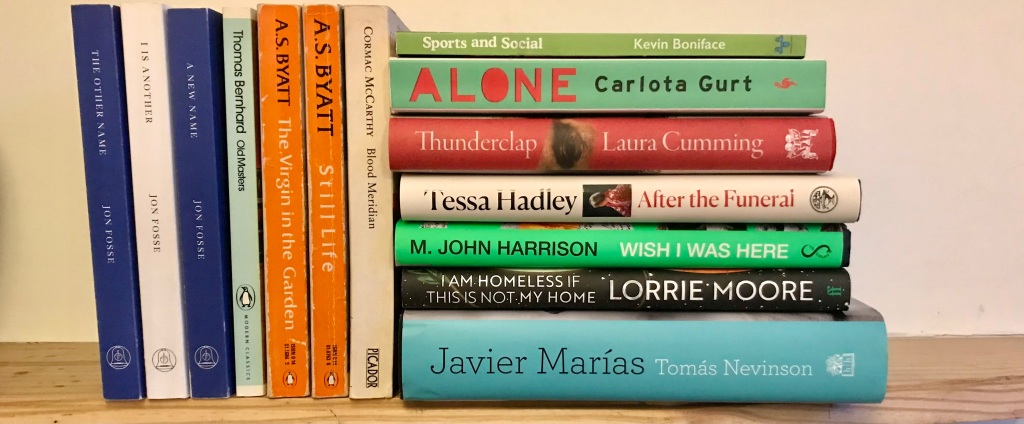

Books of the Year 2023

As for the last few years, I’m reading fewer new books, in part as my university teaching replaces book reviewing as the driver of much of my ‘strategic’ reading, and in part perhaps because of my continued and always-belated attempted to catch up with unread classics (2023: War and Peace; 2022: Moby-Dick, Ulysses, Anna Karenina; 2019-20: In Search of Lost Time; Middlemarch; 2024? I’m not sure yet…)

Anyway, here are my ‘books of the year’ – I’m keeping the title for consistency’s sake, though really this is intended as a record of my reading. In 2023, as I’ve done in some of my previous years, I kept a ‘reading thread’, which migrated halfway through the year from Twitter/X to Bluesky. (I’m keeping my X account live, really just for the purposes of promoting A Personal Anthology; I’ve deleted it from my phone, and carry on my book conversations now on Bluesky). I’m grouped the books according to i) new books, i.e. published in 2023 ii) books read by authors who died in 2023 iii) other books, with a full list at the end.

Best new books

After the Funeral by Tessa Hadley was my book of the year. She is truly a contemporary master of the short story. I delight in her rich use of language, in her ability to draw me into characters’ lives and particular perspectives (though I’m aware that, in broad sociological terms, those characters are very much like me) and in the power and deftness with which she manipulates the narrative possibilities of the short story. She’s like an osteopath, who starts off gently – you think you’re getting a massage; you feel good; you feel in good hands – but then she does something more dramatic, leaning in and applying leverage, and you feel something shift, that you didn’t know was there. ‘After the Funeral’ and ‘Funny Little Snake’ are both brilliant stories well deserving of their publication in The New Yorker. ‘Coda’ is something else: it feels more personal (though I’ve got no proof that it is), more like a piece of memoir disguised as fiction, which is not really a mode I associated with Hadley. I read or reread all her previous collections in preparation for a review of this, her fifth, for a review in the TLS, and I have to say: there would be no more pleasurable job that editing her Selected Stories – the collections all have some absolute bangers in them – though equally I’d be fascinated to see which ones she herself would pick.

Tomás Nevinson by Javier Marías, translated by Margaret Jull Costa. Not a top-notch Marías, but a solid one: Nevinson is a classic Marías sort-of-spook charged with tracking down and identifying a woman in a small Spanish town who might be a sleeper terrorist, from three possible targets, which naturally involves getting close to and even sleeping with them. I found some of the prose grating – flabbergastingly so for this writer (“we immediately began snogging and touching each other up” – I mean, come on!) – but the precision of the novel’s ethical architecture is absolutely characteristic.

Alone by Carlota Gurt, translated by Adrian Nathan West. A compelling and moving Catalunyan novel about the stupidity of thinking you can sort your life out by relocating to the country. Similar in theme to another book I read this year (Mattieu Simard’s The Country Will Bring Us No Peace) though I liked that one far less. I won’t say much about it as I read it without preconceptions and recommend it on the same terms. I will say it reminded me of The Detour by Gerbrand Bakker, which is another novel of solitude and the land, which again benefits from stepping into as into an unknown locality.

I am Homeless if This is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore. Oh boy. I love love love Moore at her best and though this aggravated as much as delighted me it’s been nagging me ever since I really want to go back and read again. [NB I have gone back to it, as my first book of 2024, and am being far less aggravated than on the first read). After a brisk, unexpected and exhilarating opening the novel seems to go into stasis, a slow series of disintegrating loops. It fails to do the thing that Moore usually seems to do quite effortlessly: keep you dizzily engaged with a cavalcade of daft gags and darkly sly sharper wit and observation. The protagonist, Finn, seems to miss what Moore usually gives her central characters: a dopey friend to dopily muddle through life with. He has a brother, Max, but he’s dying, and an ex, Lily, who, well… But all of this is done in flat dialogue wrestling with the big questions. Moore usually lets the big questions bubble up from under the tawdry minutiae of life (as, brilliantly, in A Gate at the Stairs); here, they’re front and centre. More tawdry minutiae, I say! I think part of my frustration with the novel comes from a place of ‘Creative Writing pedagogy’. Wouldn’t it be better, I think, to open up Finn’s character, show him as a teacher, his banter with the students, and his entanglement with the head’s wife? Rather than making all of that backstory, dumping it into reflection. The scene with Sigrid, for instance – her attempts to flirt with Finn – would be stronger if we’d already met her in the novel, already seen their relationship (such as it is) in action. You tell students, first you establish the ‘normal’ of the protagonist’s existence, then you throw it into confusion. So, am I giving LOORIE MOORE MA-level feedback? Well, yes. To which the response (beyond: “she’s LORRIE MOORE”) is: she’s not writing that kind of ‘normal’ novel. For every bit of LM brilliance (the gravestone reading “WELL, THAT WAS WEIRD”; the line “Death had improved her French”) there’s something off, that should or could be fixed or cut: the cat basket sliding around on the car backseat; the scene where Finn’s car spins off the road.

A Thread of Violence by Mark O’Connell. A suavely written book that digs into the true crime genre but stops short of the moral reckoning it at least flirts with: that in truth it shouldn’t exist – as a published book, at least. Will surely sit on reading lists of creative non-fiction in the future.

Tremor by Teju Cole. Read quickly and carefully (in physical not mental terms: it was bought as a Christmas present and sneakily read before being wrapped up and given ‘as new’), with the full intention of going back and reading it again. Cole is a literary intelligence for our times, that I’d drop into the Venn diagram of the contested term ‘autofiction’, not for its supposed relationship to the author’s life, but for its relation to the essay form.

Wish I Was Here by M. John Harrison. In fact I haven’t finished reading this. But I dug what I read, and will go back and finish it, but feel like I wasn’t in the right headspace for it at the time. It’s a book to sit with, to scribble on, to squint, to make work on the page. It’s not a book to do anything as basic as just read.

Sports and Social by Kevin Boniface. Stories from the master of quotidian observation that somehow avoids observational whimsy (the curse of stand-up comedy). If we build a new Voyager probe any time soon this should be on it, but failing that I’d recommend putting a copy in a shoebox and burying it in your garden, for future generations to find.

Thunderclap by Laura Cumming. A slight cheat, as I finished this on the first of January 2024. But it was a Christmas present and perfectly suited the slow, thoughtful last week of the ending year. I loved Cumming’s take on Dutch art, and how its thingness is often overlooked, and I loved the way she mixed together scraps of biography of Carel Fabritius (about whom little is known) and a memoir of her father (James Cumming, about whom little is known to me). The fragments hold each other in tension very well, but it’s not fragments for fragments’ sake. Cumming delineates a space for thinking about art, and its relationship to life, and lives, and other elements, big and small: death, sight-loss, colour-blindness, the nature of explosions, dreams, more. Tension’s not the word: it’s more like a provisional cosmology, that puts thematic and informational pieces in orbit around each other. There’s no symphonic tying-together at the end, but things are allowed back in, with new things too.

I only started underlining (in pencil: it’s a beautiful book!) towards the end. Here are some lines:

- “Open a door and the mind immediately seeks the window in the room”

- “Painting’s magnificent availability”

- Of an explosion witnessed first-hand: “a sudden nameless sound […] a strange pale rain”

There is so little known about Fabritius, with so many of his paintings lost, but really there’s so little known about any of us, the book suggests… and most of our paintings will be lost (as paintings by Cumming’s father have already been lost) but yet looking at art brings a special kind of knowledge, showing us “the intimate mind” of the artist, as of a novelist, or – as here – a writer. The love of art and of life shines through, or not shines, but diffuses, as in one of the grey Dutch skies Cummings writes about.

“But I have looked at art” she says, and she shares that looking (as does T. J. Clarke in his magnificent The Sight of Death) but she also opens up a space for looking. If “But I have looked at art” is an understatement, a compelling gesture of humility, then Cumming can also write, again towards the very end of the book, “What a glorious thing is humanity” and not have it jar, or smack of pomposity. There is much to cherish – much humanity (and what else is there in the world truly to cherish? – in Thunderclap.

Continue readingJavier Marías: Enemy of le mot juste, master of or

There’s a line near the beginning of Javier Marías’s new novel, Thus Bad Begins, that made me smile.

Muriel was very rarely confused, on the contrary, he prided himself on being very precise, although sometimes, in his search for precision, he did have a tendency to ramble.

The narrator, Juan de Veres, is describing his employer, Eduardo Muriel, but he could just as easily be describing Marías’s own writing style, which is dilatory in the extreme: it moves forward incredibly slowly, in long, involved paragraphs, trying out words, phrases and descriptions in order to see which best approaches the behaviour being described. It’s not rambling as such, nothing so random or evasive: the prose seems to move through language in circles, returning and returning to particular key terms (best exemplified by the repeated use of the words in the volume titles of his magnificent trilogy, Your Face Tomorrow: Fever, Spear, Dance, Dream, Poison, Shadow, Farewell) ; the only forward motion is, paradoxically, inwards, deeper into the psychology of the characters. The prose has great psychological penetration.

One of the ways that Marías achieves this is through comma splices, as in the sentence quoted above. Another is through the simple word ‘or’. When Marías uses ‘or’, it is not to offer logical alternatives at the level of plot, but at the level of the sentence, even at the level of the word. No word is precise enough for Marías. Or rather, words are precise, in their way, but human behaviour is so complex and ambiguous that it might take a number of alternative words to successfully describe how a person is, or behaves.

Here is a passage a few pages further on in the book:

‘What on earth has he been told about this dubious friend of his – or, rather, this friend who suddenly appears to be dubious – what can he have said or done?’ I wondered, or thought. ‘After half a life of utter clarity.’ Or perhaps that isn’t what I thought, but only how I remember it, now that I’m no longer young and am more or less the same age as Muriel was then or perhaps older.

Six ors in that little passage; two perhapses; one rather. Sometimes the or is doing a simple job, as in the last one, when the protagonist reassesses his age compared to that of his employer at the time he remembers him; sometimes it offers basic alternatives – said or done; sometimes it is an attempt to improve on the clarity of thought or expression, as in the first line.

My favourite, however, and the one I consider most characteristic of this writer I love, is the one that offers a distinction between wondered and thought. Plain synonyms, in most writers’ hands, but not for Marías. He is the master of the fine distinction, that is never fine enough. Rather than describing a character in one way, and basta!, he offers two, three or four alternatives, with the definite implication that none of them are right.

As I writer, sometimes I use a thesaurus. Like many writers I usually end up back with the word I started with. But, probably like most writers, what I’m looking for when I pick the thesaurus up, is the most precise words, le mot juste. Marías, you’d think, uses the thesaurus not to find a better word to replace the one he has, but others to add to it.

I love this style, so much so that I tried to copy it in a story I wrote. Imitation intended, at least, as sincere flattery. The story is The Story I’m Thinking Of, which you can read on the White Review site.

April reading: White Review Short Story Prize, Ben Lerner… but mostly: why I read so few women writers, and how you can help me kick the habit

Okay, so here’s my pile of books from April. Some can be dispensed with quickly: the Knausgaard I wrote about here; the Tim Parks was mentioned in my March reading, about pockets of time and site-specific reading; the Jonathan Buckley (Nostalgia) was for a review, forthcoming from The Independent; the White Review, though I read it, stands in for the shortlist of the White Review Short Story Prize, which had my story ‘The Story I’m Thinking Of’ on it.

In fact, a fair amount of April was spent fretting about that, and I came up with an ingenious way of not fretting: I read all the other stories once, quickly, so as to pick up their good points, but I read mine a dozen times or more, obsessively, until all meaning and possible good qualities had leached from it entirely, and I was convinced I wouldn’t win. Correctly, as it turned out, though I’m happy to say I didn’t guess the winner, Claire-Louise Bennett’s ‘The Lady of the House‘, the best qualities of which absolutely don’t give themselves up to skim reading online. It’s very good, on rereading, and will I think be even better when it’s read, in print, in the next issue of the journal.

That leaves Jay Griffiths and Edith Pearlman. Giffiths’ Kith, which I have only read some of, I found – as with many of the reviews that I’ve seen – disappointing. Where her previous book, Wild, seemed to vibrate with passion, this seems merely indignant, and the writing too quickly evaporates into abstractions. In Wild, Griffiths’ passion about her subject grew directly out of her first-hand experience of it – the places she had been, the things she had seen, lived and done – and the glorious baggage (the incisive and scintillating philosophical and literary reference and analysis) seemed to settle in effortlessly amongst it. Here, the first-hand experience – her memories her childhood – are too distant, too bound up in myth.

The Pearlman – her new and selected stories, Binocular Vision, I will reserve judgement on. It’s sitting by my bed, and I’m reading a story every now and then. The three that I’ve read (‘Fidelity’, ‘If Love Were All’ and ‘The Story’) have convinced me that she is a very strange writer indeed, and perhaps not best served by a collected stories like this one.

Those three stories are all very different, almost sui generis, and each carries within itself a decisive element of idiosyncrasy that it’s hard not to think of as a being close to a gimmick. They all do something very different to what they seemed to set out to do. They seem to start out like John Updike, and end up like Lydia Davis. Which makes reading them a disconcerting experience, especially when they live all together in a book like this. It makes the book seem unwieldy and inappropriate. I’d rather have them individually bound, so I can take them on one-on-one. Then they’d come with the sense that each one needs individual consideration. More on Pearlman, I hope.

The book that I was intending to write more on, this month, was the Ben Lerner, Leaving the Atocha Station, which I read quickly (overquickly) in an over-caffeinated, sleep-deprived fug in the days after not winning the White Review prize, which also involved a pretty big night’s drinking.

But my thoughts about Lerner are very much bound up in a problem which is ably represented by the book standing upright at the side of my pile: Elaine Showalter’s history of American women writers, A Jury of Her Peers. This was a birthday present from my darling sister, who, if I didn’t know her better, might have meant it as an ironic rebuke that I don’t read enough women writers. Continue reading

Today’s sermon: On sharing the planet with an immortal

Today’s text is taken from Nicholson Baker’s U&I (pg 20, in its cute little US Random House hardback), which I happened to leafing through yesterday for some other reason, when I came across these lines:

Updike was much more important to me than Barthelme as a model and influence, and now the simple knowledge that he was alive and writing and had just published one of his best books, Self-Consciousness, felt like a piece of huge luck. How fortunate I was to be alive when he was alive!

I remember being struck by this when I read the book before, because that is what I had thought, too late, on reading the obituary of Samuel Beckett, when I was 17. I was suddenly struck with the fact that I had been alive, on the planet, at the same time as this person, and with what a huge privilege that was. Beckett would go on being read down the ages, and people in the future would pause from their reading, look out the window and wonder what the world was like, back then, that it could have produced such a response – and I knew. I was there! (Okay, I wasn’t alive when he was writing most of what people would be reading, down those ages, but that was only half the point: I was enviable. I was to be envied.)

The thought, the memory, passed, and I got on with whatever I was doing, but then that evening, as I was doing the ironing, I watched the BBC4 documentary ‘American Master: A Portrait of John Adams’, during which it was mentioned that Adams was the most performed living composer, and it struck me, again, as it had not struck me since Beckett, that here was someone I was privileged to be sharing the planet with: him, creating, me, listening. Continue reading

February Reading: Knausgaard, Marías, Vanderbeke, plus a short screed on ‘Cloud Atlas’

Seeing the hoohah surrounding the release of the Matrix Bros’ film adaptation of Cloud Atlas got me thinking back to that book, which I kind of enjoyed, while finding the Russian doll structure – with each story stopping halfway through, until you get to the middle one, the sixth, which runs in full, after which you get the endings, in reverse order – frankly annoying.

Not that I’m against narrative games, but that seemed very much for the sake of it an elegant refinement of an approach to structure that was beginning to look like a piece of schtick on Mitchell’s part. No question but that he can write, but the permanent hopping around in his first three books, the refusal to commit to or ground any of his well-appointed lit fic stories, to allow them to make a claim for their own psychological truths (or wherever it is you find your value), but instead disseminate his meanings throughout the various texts in rather nebulous forms of symbolism and connectivity (to quote myself from the review of another book, best forgotten, he “scatters his thematic overtones across the centuries and leaves it to the reader to pull them together into a single chord of meaning”)… all had me irked.

Not that I’m against narrative games, but that seemed very much for the sake of it an elegant refinement of an approach to structure that was beginning to look like a piece of schtick on Mitchell’s part. No question but that he can write, but the permanent hopping around in his first three books, the refusal to commit to or ground any of his well-appointed lit fic stories, to allow them to make a claim for their own psychological truths (or wherever it is you find your value), but instead disseminate his meanings throughout the various texts in rather nebulous forms of symbolism and connectivity (to quote myself from the review of another book, best forgotten, he “scatters his thematic overtones across the centuries and leaves it to the reader to pull them together into a single chord of meaning”)… all had me irked.

In fact, I’ve only read the first three of Mitchell’s books, the Narrative Gimmick Trilogy, you might call them, and of them I most enjoyed Number9Dream. I was big into Haruki Murakami at the time, and I loved it for its breathless (its Breathless) propulsion. Cloud Atlas just seemed like an attempt to get all grown-up over something that had worked fine as a young adult fireworks display. (And I mean ‘young adult’ entirely sincerely. I was 30-odd when I read Number9Dream and I wish I’d been able to read it earlier. That book is precisely what young adults should be reading.)

Thinking about Cloud Atlas produced two thoughts: one that Steve Aylett had used something like that very structure in his novel The Inflatable Volunteer. From memory, each chapter ended at a particularly cliff-hanging moment with a character beginning a further tall tale, which is then told in the next chapter, and so on. Then, halfway through, as in Cloud Atlas, the stories start winding up, sending you back up towards the surface, the original mise-en-scene. A simpler Chinese box format than Mitchell’s, but its headlong reverse chronology (like Heart of Darkness on the wrong drugs) was hugely compelling.

To extend this thought before I get to the second one, what I didn’t like about Cloud Atlas was that it didn’t have the guts to make me care about the characters, in that particularly hokey lit fic way, which was annoying, because I like doing that, and Mitchell so clearly has the talent to write a properly moving realist novel about proper, living breathing characters, that muscle in on your life (which happened with my favourite story of the novel, ‘Letters from Zedelghem’), but he backs away from doing so, instead offering up a glossy postmodern spin on some rather mushy Eastern philosophy that, to my mind, is absolutely not a step forward from dull old honest-to-goodness realist lit fic.

The second thought about Cloud Atlas is that the reason I resented that tricksy gimmick, of layering the stories like opened novellas laid one atop the other – and that makes all of this just a preamble to my real February Reading – is because that’s how I read anyway.

Continue reading

What is ‘reading’?: A failed blog post about books

About a year ago I began writing a monthly post on this blog responding to the books that I had read over the last month – not reviews so much, nothing so considered; more a summation of what had stuck with me from those books. It’s not that I don’t like book reviews – people pay me to do those – but that I wanted to move beyond the balanced, culturally-engaged appraisal they call for to see if there was more to get out of writing about books once the books had been finished, put down, half-forgotten, and allowed to relax into the seething primordial swamp of read books, their sentences lost among the millions of other sentences read, processed, filed, erased. (It’s no surprise that I count among my favourite critical books Nicholson Baker’s U&I and Geoff Dyer’s Out of Sheer Rage.)

I kept it up for all of 2012, not always posting on time – but then not all of the books were timely books – and letting myself slip only for December. And, indeed, what I found as the year went by is that single issues, single books, tended to dominate the posts. Some months had photographs of big piles of books at the top (nine, ten, eleven books), some three, or even two. Sometimes those books were big books, and so took up lots of reading time (January 2013 I’ve been reading Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, which doesn’t leave much head space for anything else) but sometimes I had read other books but didn’t much feel like writing about them.

Then there’s the question of how you actually define reading. For a book to be read, must it be completed? Properly engaged with? Where do you draw the limits? If I’ve ‘been reading’ The Magic Mountain does that mean I’ve not ‘been reading’ anything else? No. Also by my bed is Bettany Hughes’ The Hemlock Cup: Socrates, Athens and the Search for the Good Life, which I’ve been dipping into after a discussion of philosophy books with my good friend Neil and his son Harrison, who’s just starting to study the subject at school. As part of that discussion I took down from the shelf my favourite philosophical anthology Porcupines – that got read, too, a bit.

Last Saturday, while supposedly watching Borgen on television with my wife, I found myself dipping into another of my favourite ‘dipping into’ books, Clive James’s book of essays Cultural Amnesia; I read two or three entries, including his spirited takedown of Walter Benjamin Continue reading

A short screed: When is a not-a-roman-à-clef a roman-à-clef after all?

I’d been meaning to post this up for a few days now but a brief Twitter conversation riffing on a Tweet from @nikeshshukla (Writers LOVE it when people ask how much of their work is based on their real life.”) has given me the impetus to quickly get it up there.

As part of an extended, second-half-of-the-year Javier Marías jag I recently read his early novel All Souls and immediately followed it with The Dark Back of Time, the memoir he wrote in response to the sort of scandal that arose following the novel’s publication, which many people read as being based on his two years spent teaching at Cambridge. The memoir/essay is fine reading (not as exquisite as the novels) and is sensitive and sensible on the subject of exactly what links it is possible, in the end, to draw between fiction and ‘real life’.

But when I came to this passage, I just had to laugh. In it, Marías is back in Cambridge, talking to some of his old friends about the novel, which is already the subject of gossip. This is the novelist himself speaking:

“Well, I still don’t know exactly what kind of novel it will be, I don’t know much about my books until I’m done with them, and even then. But of course it won’t be a roman à clef about all of you. I don’t think my colleagues should worry about that. Though a few may insist on seeing it that way, nevertheless, or believe they recognize descriptions of themselves.

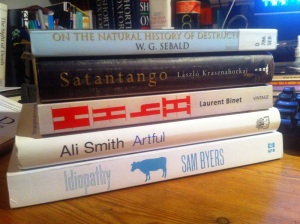

November reading: Krasznahorkai, Binet, Byers

Reading Lászlo Krasznahorkai’s Satantango was a struggle. I wish it hadn’t been, and I’m the first to argue for the improving qualities of difficult books, but this was one that I persevered with in the face of a dwindling conviction that I was going to be able to make any sense of it.

I picked it up largely out of respect for the names on the cover and title page – admiring quotes from WG Sebald (who has loomed large in my reading this year) and Susan Sontag, and the added interest of reading the translation of George Szirtes, lest we forget he is significantly more substantial a literary presence than his marvellous Twitter feed.

I knew nothing about the author, nothing about the book, and took the opportunity to add nothing to this sum before reading – as someone pointed out about the Olympic opening ceremony, the opportunity to sit down to a cultural experience with absolutely no preconceptions is a rare one. Nor have I read anything about the book since finishing it, which I am tempted to do now, in part to see what it is I missed. For a lot of its incredibly dense 270 pages I was trying, trying so hard, to find meaning, discern allegory, pick out the thread or symbol or standpoint that would allow me to take a view on the book as a whole.

I knew nothing about the author, nothing about the book, and took the opportunity to add nothing to this sum before reading – as someone pointed out about the Olympic opening ceremony, the opportunity to sit down to a cultural experience with absolutely no preconceptions is a rare one. Nor have I read anything about the book since finishing it, which I am tempted to do now, in part to see what it is I missed. For a lot of its incredibly dense 270 pages I was trying, trying so hard, to find meaning, discern allegory, pick out the thread or symbol or standpoint that would allow me to take a view on the book as a whole.

Forgive the clumsy phrasing, but never has there been a book so impossible to read between the lines of. Continue reading

September reading: Norfolk, Gough, Marías

One: I have a dysfunctional relationship with books, and authors. And, two: There is no functional relationship available, that I know of.

Take Lawrence Norfolk. I read his first novel, Lemprière’s Dictionary, in paperback, many years ago, and found it exhilaratingly different from my usual run of reading, a historical novel that confidently brushed aside my preconceptions of the genre, that boomed outwards in an explosion of character and description and action in ways I found exhaustingly brilliant. He followed this with a similar historical fantasy, The Pope’s Rhinoceros, which I picked up somewhere along the way, but never read, beyond its barn-storming opening section, beginning: “This sea was once a lake of ice.”

In 2000 his third novel came out, In The Shape of a Boar, and this I read on publication, and was bowled over by it in ways that knocked me a different kind of sideways from his previous books. It was, and is, an unprecedented novel. It comes in three parts, the first a mockery-free mock-epic narrating a boar hunt in Ancient Greece, complete with copious footnotes pointing to sources in the kind of Classical literature of which I knew little but was nonetheless in awe of. The second, and longest, part takes place at the end of the Second World War and treats love and betrayal among Greek partisans tracking down Nazis. It is, to my knowledge, the only remotely modern thing Norfolk has ever written. The book ends with a very short coda that joins the two sections in a way that in Creative Writing class I would have to call ‘thematically’, but that does not go very far at all in explaining how it does it.

In 2000 his third novel came out, In The Shape of a Boar, and this I read on publication, and was bowled over by it in ways that knocked me a different kind of sideways from his previous books. It was, and is, an unprecedented novel. It comes in three parts, the first a mockery-free mock-epic narrating a boar hunt in Ancient Greece, complete with copious footnotes pointing to sources in the kind of Classical literature of which I knew little but was nonetheless in awe of. The second, and longest, part takes place at the end of the Second World War and treats love and betrayal among Greek partisans tracking down Nazis. It is, to my knowledge, the only remotely modern thing Norfolk has ever written. The book ends with a very short coda that joins the two sections in a way that in Creative Writing class I would have to call ‘thematically’, but that does not go very far at all in explaining how it does it.

This felt like the most exciting contemporary novel I had ever read: unfathomable and yet moving, miles above me in terms of intellect (and seductive because of this) while seeming to offer the possibility of understanding despite this. It reached down, or at least waved, from the heights on which it stood. Continue reading

August reading: Marías, Bolaño, Villalobos, Rivière

Ah, August reading! From the date of this post it is clear that the days of August reading are gone. School and work and house and chores have breached the walls and flooded back in to cover that prized, fertile land, with its flowers of leisure that bloom but once a year.

August means holidays, which means, most often, camping somewhere warm, and thus the chance to do that thing I never really liked to do on holidays before I had kids: lie by a swimming pool, slathered in suncream, while obnoxious children (not all of them my own) and undressed, unlookatable (for a variety of reasons) adults screech and splash and loll, and give myself over to the hour-by-hour mental massage of immersion in a good, long book. How else do you think I read 2666? Or The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle?

This year I decided to take with me the final volume of Javier Marías’s mammoth novel Your Face Tomorrow, which comes in seven parts: Fever, Spear, Dance, Dream, Poison, Shadow and Farewell, two parts each in the first two volumes, the last three in the third. I remember when I read the first volume, it was on a different kind of holiday, in a cottage on the damp, misty north Norfolk coast, not so sure about the second, but after a couple of failed housebound attempts at the 544pp third volume I knew I needed time and space to read it, which I definitely wanted to do.

This year I decided to take with me the final volume of Javier Marías’s mammoth novel Your Face Tomorrow, which comes in seven parts: Fever, Spear, Dance, Dream, Poison, Shadow and Farewell, two parts each in the first two volumes, the last three in the third. I remember when I read the first volume, it was on a different kind of holiday, in a cottage on the damp, misty north Norfolk coast, not so sure about the second, but after a couple of failed housebound attempts at the 544pp third volume I knew I needed time and space to read it, which I definitely wanted to do.

Time and space is needed not just because of the length (you don’t need to go on holiday to read Ulysses, it suits itself quite naturally to the jittery stop-start motion of modern city life) but because of Marías’s writing style, which isn’t that far removed from that of Thomas Bernhard in the length of its sentences and paragraphs. Pages look like dry plateaux, with the cracks of a former riverbed only appearing occasionally, Continue reading