Tagged: Sheila Heti

Books of the Year 2018

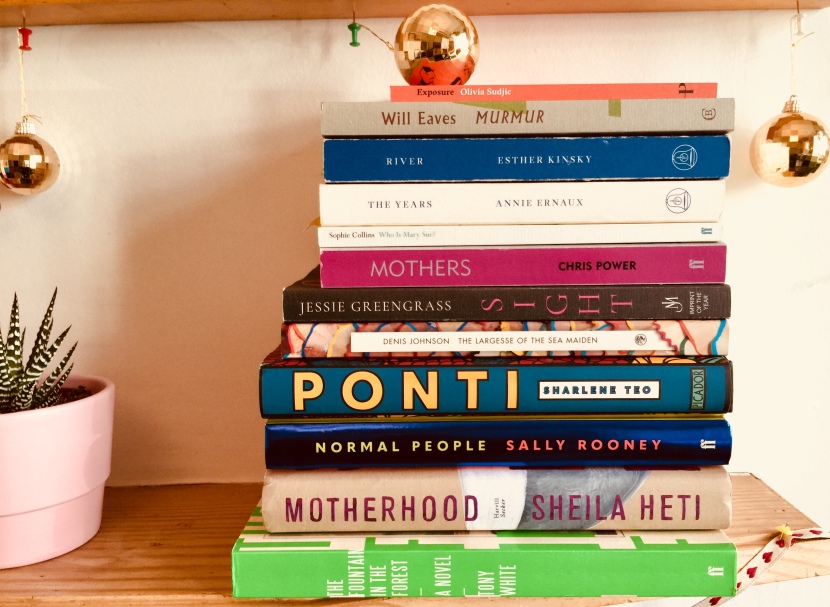

In going back through my Monthly Reading blog posts for the year I’ve identified 12 books published this year that I more than thoroughly enjoyed, that I think are great to brilliant examples of what they do, and that I feel will frame and influence my future reading. (A thirteenth, The Penguin Book of the Prose Poem, is not pictured because I’ve loaned it to someone.)

In going back through my Monthly Reading blog posts for the year I’ve identified 12 books published this year that I more than thoroughly enjoyed, that I think are great to brilliant examples of what they do, and that I feel will frame and influence my future reading. (A thirteenth, The Penguin Book of the Prose Poem, is not pictured because I’ve loaned it to someone.)

A quick scan of the books shows me Faber have had an excellent year – four of the twelve – and it’s no surprise that Fitzcarraldo and CB Editions show up, both publishers very close to my heart. (It’s only fair to point out that those books were complimentary/review copies, as was the Heti and the Johnson. All others bought by me.) And a shout-out to Peninsula Press, whose £6 pocket essays are a welcome intervention to the literary scene. Eight women to four men writers. Only one BAME writer. Two books in translation. Two US writers.

I’m not going to write at length again about each book, but rather provide links to the original monthly blog posts or reviews, but I do want to take a moment again to think about Sally Rooney’s Normal People, which seems to stand out for me as a Book of the Year in a more than personal way. In a year that the “difficulty” or otherwise of Anna Burns’ Milkman (which I haven’t read, and very much want to) became a hot topic, I think it’s worth considering just how un-difficult Rooney’s book is, and how that absence of difficulty, that simplicity, that ease-of-reading – allied to the novel’s clear intelligence – is central to its success, both as a novel unto itself, and more widely. You can see precisely why an organisation like Waterstones would make it Book of the Year: it is utterly approachable; it finds an uncomplicated way of narrating complicated lives and issues.

I read Normal People in September, a borrowed copy, but bought it again recently, and was pleased to find that Marianne and Connell drifted back into my life without so much as a shrug. I think it’s a brilliant accomplishment, while I’m also very aware that this is a book aimed squarely at me: white, middle class, educated. I embrace it because it reflects my situation and concerns, and in addition romanticises and bolsters the generation I now find myself teaching at university. I want it to work, and it does, for me.

Yet I am astonished that it does so much with so little. Present tense, shifting close third person narration. Unpunctuated dialogue. A drifting narrative almost without plot, chopped into dated sections.

I wrote here about how I didn’t want to have to buy it in hardback (though I did) and I wrote here about how these anti-technical techniques made the book a potentially dangerous model for Creative Writing students – it looks like you can get away with Not Much – and it is true that Rooney’s book seems to throw a harsh light on some of the other books on my list, sitting with it in that stack. They seem to be trying so hard: Jessie Greengrass’s Sight is so unashamedly intelligent, Will Eaves’s Murmur so oblique and poetic, Tony White’s The Fountain in the Forest so formally inventive (and in a number of different ways), Sheila Heti’s Motherhood so disingenuous in its informality, its seeming-naturalness. (I hope it’s clear that I love these books for the very aspects I seem to disparage.)

By contrast, Normal People seems written at what Roland Barthes called ‘writing degree zero’, by which he meant writing with no pretension to Literature – “a style of absence which is almost an ideal absence of style”. His model for this is Camus’ L’Étranger, and the comparison seems apt, except that L’Étranger is written in the first person. Everything extraneous is taken out. It’s interesting to note that David Szalay’s All That Man Is is written in a very similar way to Normal People, the only real difference being the use of single quote marks for dialogue. Yet they seem a world apart to me. Continue reading

May Reading: Heti, Forna, Harris, Chabon – or ‘Autofiction vs the novel’ and ‘Value for money in bookbuying’

This is not my usual monthly reading post. Instead, I’m using four books I read this month as a springboard into a pair of barely-thought-through meander/rants.

This is not my usual monthly reading post. Instead, I’m using four books I read this month as a springboard into a pair of barely-thought-through meander/rants.

Autofiction vs ‘the novel’, followed by Value for money in bookbuying. If you fancy that, please read on:

Here are two interesting novels that seem, to me, to epitomise the two dominant modes of being for the novel at the moment, rather as Netherland and Remainder did for Zadie Smith in her much-discussed ‘Two Paths for the Novel’ essay, which you can also read in Changing My Mind. For Joseph O’Neill’s Netherland, used by Smith to represent the way things used to be, may I suggest Happiness by Aminatta Forna, a writer I’d never read till now, and maybe never would have if I hadn’t been given the book by my parents as a birthday present. Smith set in opposition to O’Neill’s Franzen-esque ‘well-made novel’ Tom McCarthy’s Remainder, a more difficult and dicey proposition that, now, I’d be tempted to call ‘neo-postmodern’. In place of that, how about Sheila Heti’s Motherhood, as good a representative of the ‘autofiction’ genre as you can imagine, outside of Rachel Cusk’s Outline/Transit/Kudos trilogy.

I won’t say too much about the Heti, as I have a review of it forthcoming in the excellent Brixton Review of Books, but I will say that, although I am a big fan of autofiction as a genre, I am becoming annoyed with its willingness to play fast and loose with the title ‘novel’ – even if it’s not the writers themselves who do so, but rather than nebulous publishing-promotional-journalistic apparatus that surrounds them. When I think of the books that have most impressed me so far this year, I think of Esther Kinsky’s River, Jessie Greengrass’s Sight and Heti’s Motherhood – and that’s not counting the latest Cusk, which I haven’t read yet, but which if it is as good as Outline and Transit, will certainly be up there too. All of those are books that seem to come under the autofiction bracket – though Kinsky’s blue Fitzcarraldo livery would seem to mark it as fiction rather than non-, and Sight gets called a novel on the blurb.

Now, what I like about autofiction is that it problematises the very notion of what a ‘novel’ is, but what I don’t like is that in doing so it seems to sideline the very worthy, if unfashionable idea of what a novel used to be. It seems at time to equate the view that the line between fiction and non-fiction is blurred, and in fact more of a zone than a line with a wholesale annexation of the fictional landscape. As if autofiction wants to be what a novel should be. This doubtless reads like some kind of awful exaggeration, but it does seem to suggest to me rather where we headed – which is a place where to write a good old-fashioned novel, with rounded characters, and realist description, and manufactured plots, is, oh dear me yes, something that is beyond the bounds of tastefulness. As if to write a traditional novel is akin to producing ‘likeable’ characters. Continue reading

May Reading: Heti, Levy, Luiselli, Müller, Butts

Tattoo of Sheila Heti from a set by Joanna Walsh (@badaude) available from www.badaude.typepad.com

When I set out to read only women writers for the months of May, June and July, it was with the idea that the exercise might help me focus my mind on the prejudices that might be lurking in my lizard reading brain, that preconscious part of my literary apparatus that nudges me towards male books, and male books of a certain tenor.

Basically, if you asked me to name the books and writers that make up my personal (contemporary) canon, you would hear names like Javier Marías, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Geoff Dyer, Don DeLillo, David Foster Wallace, WG Sebald, Alan Warner, Roberto Bolaño, Ben Marcus, Michel Houellebecq, Alan Hollinghurst, and so on, before you heard a female name. These are the writers who have produced the books that I value the highest, that have the greatest worth, that tell me the most, and tell me best, about what it is to be a thinking human in the world today.

Or are they just telling me about myself? Continue reading

April reading: White Review Short Story Prize, Ben Lerner… but mostly: why I read so few women writers, and how you can help me kick the habit

Okay, so here’s my pile of books from April. Some can be dispensed with quickly: the Knausgaard I wrote about here; the Tim Parks was mentioned in my March reading, about pockets of time and site-specific reading; the Jonathan Buckley (Nostalgia) was for a review, forthcoming from The Independent; the White Review, though I read it, stands in for the shortlist of the White Review Short Story Prize, which had my story ‘The Story I’m Thinking Of’ on it.

In fact, a fair amount of April was spent fretting about that, and I came up with an ingenious way of not fretting: I read all the other stories once, quickly, so as to pick up their good points, but I read mine a dozen times or more, obsessively, until all meaning and possible good qualities had leached from it entirely, and I was convinced I wouldn’t win. Correctly, as it turned out, though I’m happy to say I didn’t guess the winner, Claire-Louise Bennett’s ‘The Lady of the House‘, the best qualities of which absolutely don’t give themselves up to skim reading online. It’s very good, on rereading, and will I think be even better when it’s read, in print, in the next issue of the journal.

That leaves Jay Griffiths and Edith Pearlman. Giffiths’ Kith, which I have only read some of, I found – as with many of the reviews that I’ve seen – disappointing. Where her previous book, Wild, seemed to vibrate with passion, this seems merely indignant, and the writing too quickly evaporates into abstractions. In Wild, Griffiths’ passion about her subject grew directly out of her first-hand experience of it – the places she had been, the things she had seen, lived and done – and the glorious baggage (the incisive and scintillating philosophical and literary reference and analysis) seemed to settle in effortlessly amongst it. Here, the first-hand experience – her memories her childhood – are too distant, too bound up in myth.

The Pearlman – her new and selected stories, Binocular Vision, I will reserve judgement on. It’s sitting by my bed, and I’m reading a story every now and then. The three that I’ve read (‘Fidelity’, ‘If Love Were All’ and ‘The Story’) have convinced me that she is a very strange writer indeed, and perhaps not best served by a collected stories like this one.

Those three stories are all very different, almost sui generis, and each carries within itself a decisive element of idiosyncrasy that it’s hard not to think of as a being close to a gimmick. They all do something very different to what they seemed to set out to do. They seem to start out like John Updike, and end up like Lydia Davis. Which makes reading them a disconcerting experience, especially when they live all together in a book like this. It makes the book seem unwieldy and inappropriate. I’d rather have them individually bound, so I can take them on one-on-one. Then they’d come with the sense that each one needs individual consideration. More on Pearlman, I hope.

The book that I was intending to write more on, this month, was the Ben Lerner, Leaving the Atocha Station, which I read quickly (overquickly) in an over-caffeinated, sleep-deprived fug in the days after not winning the White Review prize, which also involved a pretty big night’s drinking.

But my thoughts about Lerner are very much bound up in a problem which is ably represented by the book standing upright at the side of my pile: Elaine Showalter’s history of American women writers, A Jury of Her Peers. This was a birthday present from my darling sister, who, if I didn’t know her better, might have meant it as an ironic rebuke that I don’t read enough women writers. Continue reading