Category: Uncategorized

‘Spring Journal’ a year on: anniversary and review

On Friday 19th March 2021 it will be one calendar year since I lay on a sofa, phone in hand, and had the idle thought that one could tweet about the impending coronavirus pandemic, and the lockdown that had just started, in the form of a mash-up with / homage to / pastiche of Louis MacNeice’s ‘Autumn Journal’. I created a new account (that’s one of the things I love about Twitter as a creative platform; you can put ideas into action with no planning or forethought), grabbed my MacNeice Selected Poems paperback from the shelves, to copy those famous opening lines, and posted two tweets, that same evening. Here they are:

And here are the corresponding opening lines from MacNeice:

Close and slow, summer is ending in Hampshire,

Ebbing away down ramps of shaven lawn where close-clipped yew

Insulates the lives of retired generals and admirals

And the spyglasses hung in the hall and the prayer-books ready in the pew

And August going out to the tin trumpets of nasturtiums

And the sunflowers’ Salvation Army blare of brass

And the spinster sitting in a deck-chair picking up stitches

Not raising her eyes to the noise of the ’planes that pass

I carried on Tweeting my version of MacNeice in sporadic bursts over the next few weeks (I particularly remember standing in the aisle at Sainsbury’s Tweeting about standing Tweeting in the aisle at Sainsbury’s) and maybe the whole thing would have fizzled out if David Collard hadn’t asked if would like to feature the poem on his online salon A Leap in the Dark, which ran on Friday and Saturday evenings right through lockdown, on Zoom. It was a typically generous offer, but David’s stroke of brilliance was to invite, or persuade, Northern Irish novelist and actor Michael Hughes to do the readings – a canto a week, starting in early April, and running through until I had matched MacNeice’s 24 cantos. Michael read the final canto as part of a full read-through of my poem on Friday 28th August.

As it happens, the anniversary of the poem’s inception coincides with the first review of the book of the poem, which was published by CB Editions in December, after a typically nimble quick turnaround by Charles Boyle.

Tristram Fane Saunders in the Times Literary Supplement starts by setting the poem against the responses from more famous names (Don Paterson, Paul Muldoon, Glyn Maxwell), and is generous in his estimation of how my poem measures up to its inspiration and model:

aiming somewhere halfway between cheap pastiche and serious homage, Gibbs hits his mark. He nails Autumn Journal’s casual, yawning metres and late-to-the-party rhymes, its balance of didacticism and doubt.

You can read the whole review here.

(And if you have the print copy of the paper, you can have the additional thrill of turning the page to find, recto to my review’s verso, a review by Michael Hughes himself, of Anatomy of a Killing, by Ian Cobain.)

This anniversary also coincides with the vigil for Sarah Everard and protest against male violence on Clapham Common, so appallingly handled by the Met Police, which I mention only to point out the obvious fact that the pandemic only brought to the surface frustrations and inequalities that had been brewing and burning for much longer. And that if it felt like the six months during which I wrote the poem happened to have given me material to bounce at MacNeice, as it were, as a sounding board, then that’s missing the point. Whenever this had happened, these things or something like them would have happened, because they’re always happening.

The lines that Charles Boyle chose to put on the back of his edition of ‘Spring Journal’ were these:

Too many are dead, but jobs are dying too, all over.

The virus reveals the flaw

In our way of living: the rich fly it around the planet

And dump it on the doorsteps of the poor.

And the fact that the murder of Sarah Everard, and the way it triggered deep-lying anger about structural misogyny in our society, seems to repeat what happened last year when the murder of George Floyd did the same for structural racism, only goes to show that we are stuck in a cycle. The anniversary puts us no further forward in the kind of world we want to live in, and nothing to show for the lesson of so many dead.

As I wrote in August, in the penultimate canto of my poem, addressing MacNeice:

And then autumn will come,

And I’ll pass back the baton,

Let you handle your natural season,

And I’ll be there waiting, in March, when you’re done.

For as long as there’s something vicious looming

Beyond the horizon, and just as long

As we keep on getting things hopelessly wrong,

We can keep this thing turning, from poem to poem.

Fiction Friday at The Common Breath

The editors Kirsten and Brian at The Common Breath kindly invited me to contribute to their Fiction Friday segment, with a series of bookish questions to answer.

Click here if you want to find out what book most influenced me as a young person, the books that get me through hard times, my favourite literary character and novel ending, my idea of a great novel, and a book that disappointed me.

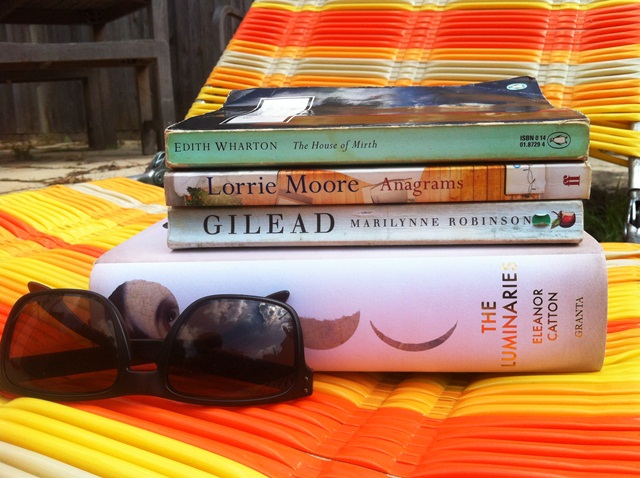

(Clues in the cover image, but you’ll have to work out which is which, and – oh horror! – which book couldn’t I actually find? Where is it! Where is it!)

Story and reading: ‘A Prolonged Kiss’

It was great to see this story published in The Lonely Crowd at the end of 2020, in their bumper five-year anniversary issue, no less. It’s a story about the theatre, about acting… grown out of an idea I had years and years ago (about how interesting it would be to watch a play every night, through it’s run, to see how it changes, grows and evolves) and brought to life in 2016, when I saw Jonathan Kent’s production of The Seagull at the National Theatre.

Here is the opening paragraph:

The kiss comes at the end of Act Three, just before the interval. It’s really what the play has been leading up to all along, and its high point. We try hard, but the fourth act is an anti-climax. Which is perhaps the point – new forms, new forms – but still you wish, with all due respect to the author, that it was stronger.

And here is a link to me reading the five minutes of it for The Lonely Crowd‘s Winter Reading series. Many thanks to John Lavin for publishing it. Do get yourself a copy, here!

And here is a link to a short piece I wrote for The Lonely Crowd‘s website about the writing of the story.

‘Spring Journal’ coming in book form… very soon

In hugely exciting news I can now announce that Spring Journal will be published as a book by CB Editions before the end of 2020.

The publisher says: “Spring Journal is an honest, angry, sad, thoughtful, appalled, urgent act of witness to this lousy year. Why would anyone want to be reminded? Those who have followed the week-by-week reading-aloud of the poem by Michael Hughes on David Collard’s Leaps-in-the-Dark on Zoom know that this is not a statistical summary or an op-ed piece; that something cumulative has been building, and that its sharing has been important. The poem itself is deeply sceptical of exaggerated or romantic notions of what poetry can do, or is for; it feels nevertheless, in part because of this scepticism, a necessary work.”

Huge thanks to Charles Boyle at CB Editions for this mark of confidence. CB Editions is one of my favourite British small presses, and it’s marvellous to see how it turn around ‘on a sixpence’ as Boyle puts it, to publish the poem while it’s still hot and, hopefully, vital. More details in the CB Editions newsletter, here.

And full information about Spring Journal on the dedicated web page on this blog, here.

‘Spring Journal’ finale and reading: 28th August 2020!

So as some readers of this blog and my Twitter feed will know, I’ve spent the last three months writing a long poem, ‘Spring Journal’, in response to the coronavirus pandemic and other aspects of the news in 2020, but taking its cues from Louis MacNeice’s great 1939 poem ‘Autumn Journal’, in which the poet mixed reaction to the looming second world war with more personal reflections.

What started as an impromptu Twitter experiment was given more solid form when David Collard invited me to present the poem as an ongoing contribution to his series of online literary salons, ‘A Leap in the Dark’. So, from early April onwards I wrote a canto a week, and actor and novelist Michael Hughes read it, on Friday evening.

Cantos were drafted on a dedicated Twitter account, Spring Journal, and edited for publication on my blog here.

Now we are approaching the end of the project, as dictated by the 24 cantos of MacNeice’s poem, and David has magnanimously handed over an entire ‘Leap’ to mark the occasion, with a full read-through of the poem, to end with the first reading of canto XXIV.

This will take place on Friday 28th August, and will be – for me at least – a thrilling experience. Michael Hughes will be reading half of the cantos, with a series of guest readers doing the rest. There will also be a musical contribution specially composed for the event by Helen Ottaway.

Like all Leaps in the Dark this will be invitation only, for usual online security reasons. If you have already attended one of David’s Leaps you’ll be on the mailing list and so will get an invitation. If not, and you’d like to attend this special event, then please use the contact form below and I’ll pass on your details to David.

(The event will be recorded and attendance assumes acceptance of this. Attendees will be asked to keep their Zoom video feeds on, rather than blacked out.)

NB Please drop a line in the Message box saying how much you love Spring Journal so I know you’re not a bot!

News round up: Dyer, Adultery and a riddle solution

A few things that have happened, recently, that I’m keen to point people towards:

- Having been published in both Lighthouse and Salt’s Best British Short Stories 2014, I’m very pleased to say that my short story ‘The Faber Book of Adultery‘ is now online as part of Issue 83 of The Barcelona Review. Read it here. (And there’s a lovely reading of it by Lee Upton here.)

- A paper I gave at Birkbeck’s conference on Geoff Dyer earlier in the year appears in the Winter 2015 issue of The Threepenny Review, and again you can find it online. Read ‘But Funny: Geoff Dyer and Comic Writing‘ here.

- I’ve added a page to this site for anyone who’s read ‘Randall‘ and either doesn’t know the answer to the riddle it ends on, or wants to check if they guessed it right. Click here to do so. (And if you’ve read ‘Randall’, why not review or rate it at Goodreads?)

- Finally, if you’ve not heard about my current blogging side-project to read all 52 of Melville House’s ‘The Art of the Novella‘ novellas in a year, then you can find out about it here.

Today’s sermon: Seeing with Poussin’s eyes

This may be one of the most embarrassingly obvious aesthetic observations every made, but it occurred to me, the other night, as I enjoyed a late viewing at the Dulwich Picture Gallery, that to stand in front of a painting of a certain type – of a certain size and scale – is to become intimate with the artist in a very particular way. It is, and I gawped at myself as I thought this, to see with their eyes.

The gallery was quiet, I was there to see the Hockney prints, but took advantage of the near-total absence of people (not least children, not least my own children) to wander rooms I knew well, but at my own pace, and without distraction.

I was looking at a Poussin – it doesn’t really matter which one – and it occurred to me that I was standing in relation to it exactly as he had stood to paint it. It felt like my gaze was caught in some spectral zone, that my eyes were haunted by his, commanded by his, and that I was seeing what he had seen, centuries ago.

Can I explain this thought? Or rather: can I explain the feeling that it was somehow important?

It wouldn’t happen with music. It wouldn’t happen with prose, or poetry, or drama, or film, or dance – or even, really, sculpture.

To create the painting, the artist would have had to stand in relation to the canvas exactly where I was standing. When he lifted the brush the first time, he was standing where I stood. To see what he had created, and decide it was finished, ditto. Continue reading

August Reading: Catton, Wharton, Moore, Robinson

August, August, August… disappearing into the rear-view mirror of the year, always the saddest sensation. Gone the sun, gone the skip and bounce in the day, gone the time for reading.

I am now firmly stuck in the middle part of life where August means school holidays, which means a couple of weeks away somewhere hot, which means camping and a pool or beach and the opportunity to read unencumbered by home life and academic/journalistic imperatives, while the kids divebomb around me. But I can read what I want.

What I took away with me this year was Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries (sadly leaving behind Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers because of space considerations), and three paperbacks from my Myopic/Misogynist reading list of women writers: Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth, Lorrie Moore’s Anagrams and Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead.

The Luminaries, in a way, is the perfect intelligent person’s holiday read. It is a mystery story (keeps you reading), and a meticulously built historical fiction (allows you to drift away into a fully-imagined, fully-upholstered reverie), but it is also presented via a structure as intricate and labyrinthine as a spider’s web (you need to have the time to concentrate). Like the other ‘big book’ on the Man Booker longlist, Richard House’s The Kills, it wouldn’t necessarily be something you’d want to read in snippets, tired, at bedtime. Both are fractured narratives, with various versions of events orbiting a ‘truth’ that the reader is tasked with putting together themselves.

Of course, the risk with this – with all mystery stories, i.e. with all stories that include the past as a dimension to be explored – is that the myriad possible ‘truths’ thrown up in the earlier sections of the book may well be tastier meat than the ‘true’ truth exposed at the end. Continue reading

Ambushed by Pixies on the school run: how Pop Music works

I strongly believe that it’s perfectly healthy to get obsessed, every now and then, with a piece of pop music. It happened with Patti Smith’s ‘Birdland’ (post here), it happened with The National’s ‘Bloodbuzz Ohio’ (post pending) and it happened last week with the Pixies’ song ‘Hey’, from their Doolittle album.

It happened like this. It was the afternoon. I’d been working at the computer at home, and it was time to collect the kids from school. (Sad to say, most of the time they go to and from school in the car. It’s a 35 minute walk, up a hill. I know, I know. I did walk to get them today.)

I got into the car, plugged in my iphone and set it to shuffle, and pressed the ignition button. “Hey! Been trying to meet you…” I turned the car and set off. It wasn’t until a minute or so into the song that I realised something was going on: I didn’t know how the song had got to where it was from where it had started. (It’s not my favourite Pixies song, far from it. If you asked me to name my top ten Pixies songs, it probably wouldn’t occur to me.)

I whacked up the volume (Dylan’s exhortation to ‘play fucking loud’ seemed entirely appropriate) and set the song back to the start. By the time we had got back to the middle of the song I was convinced not so much that it was the best thing the band had ever recorded, but that it was, effectively, the only piece of recorded music in existence. Continue reading

Fragment / aphorism / tweet

Going out to sit in a doctor’s waiting room I picked up Lars Iyer’s Dogma to keep me company and, in the few minutes the sadly super-efficient NHS kept me waiting, I was reminded quite how enjoyable it is. Just pitched in to the middle and came up with stuff like this:

What is it that keeps him from cutting his own throat?, W. wonders. What is it that keeps me from cutting mine?

We want to see how it all ends, he says. We want to see how it will all turn out. But this is how it ends. This is how it will all turn out.

Wonderful, beautiful stuff, that sticks its neck out, then pans back to see what the rest of the body is doing – it’s twitching convulsively, of course – and to show how much further out the rest of the body is than the poor old neck and head.

When I covered Dogma briefly in my January reading round-up, I said I thought it worked better as tweets or blog posts than a novel. Now I’m not sure. I think it benefits from being on paper – the veneer of respectability it gives – but I still don’t rate it as a novel particularly (though I doubt Iyer is aiming for it to be that kind of novel). It works best as a book picked up and “dipped into” (in that godawful phrase) and put down again. The tantalising thought that all these bits and pieces might coalesce into some kind of fulfilling, developing narrative is present on every page, and is rewarding as such even when you know that no such thing occurs. Continue reading