Category: Today’s sermon

‘After my own heart’: an occasional post after Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence

I was reading Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence last night, in the way that you’re supposed to, dipping into it, looking for something to snag my interest – either the writer of the sentence in question, or the sentence itself, or something Dillon might have to say – and I alighted on his section on Elizabeth Bowen, whose stories I also happen to haphazardly reading at the moment, because I’m reading Tessa Hadley’s stories, Hadley being a fan and literary descendent of sorts of Bowen… and, anyway, I read this passage:

As I write, I’m two thirds of the way through A Time in Rome, which [Bowen] published in 1960, and I think I have found, again, a writer after my own heart. How many times does it happen, dare it happen, in a life of reading? A dozen, maybe? There is a difference between the writers you can read and admire all your life, and the others, the voices for whom you feel some more intimate affinity. Could Elizabeth Bowen be turning swiftly into one of the latter, on account of her amazing sentences?

Which is marvellous, and sparked two particular thoughts, last night, and has sparked a couple more, this morning, as I sit down to write, on a Bank Holiday Sunday morning, at just gone 8am. There’s one, on the phrase “after my own heart”, that I really want to get to, so I’ll try to dispatch the other ones briefly.

Firstly, the word ‘affinity’, which is obviously an important word for Dillon: it was the name of Dillon’s next book, after all. It could just as easily have been the title of this one. What interests me about the word, however, is its aura of neutrality. When we think of the connections that get built between – as here – us as individual readers, and particular writers, we tend to look to one or the other as the active agent in the relationship. Either the writer is a genius – they seduce me, impress or overawe me – or I love the writer, I find something particular in them. But an affinity is bipartisan, and objective, as if unwilled by either. The chemical usage of the word is the most critically productive one, especially after Goethe applied it to human relationships in Elective Affinities, but in fact the original meaning was to do with relationships – in particular relationships not linked by blood, such as marriage, or god-parentship. I suppose, contra Goethe, what I like about the term is that these affinities that Dillon is talking about seem to be un- or non-elective, but weirdly, inexorably fated.

(NB I haven’t read Affinities yet, so maybe Dillon goes into all this in his book.)

The other brief thought from this morning was that, although Dillon does talk about Bowen’s fiction in his piece on her, the sentence he picks to write about is from her sort-of-travel book A Time in Rome. And this made me think of the death, last week, of Martin Amis, and how much of the online critical chat had an undercurrent of favouring the non-fiction (the journalism, and the first memoir) over the fiction (with a few exceptions, usually involving Money), and I wondered if anyone had really considered, at length, the legacy of writers that had written both fiction and non-fiction, and what it meant when one was favoured over the other. Susan Sontag wanted to be remembered as a novelist, but isn’t, and won’t be. It would surely appal Amis if he felt that it was his book reviews and interviews that we remembered him for. Geoff Dyer does talk about this a bit with reference to Lawrence in Out of Sheer Rage, but I’d like to read something broader. If a writer has a style, and that style is to an extent consistent over their fiction and non-fiction, then what are the conditions by which they become remembered, and stay read, after their death, for one rather than the other? Or, alternatively, is there a difference in terms of how a similar style applies to fiction, and non-fiction?

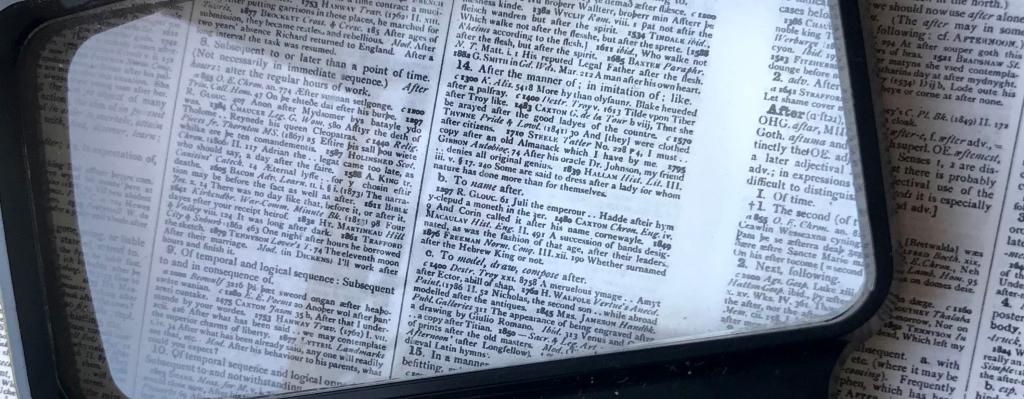

Now to the original point I wanted to make. Dillon’s paragraph on his relationship to Bowen is lovely, and I’m sure many readers will relate to it, as I did, but I was particularly struck by the phrase a writer after my own heart. “After my own heart” – it’s a strange and wonderful idiom, and sent me – it’s a Bank Holiday weekend – to the dictionary. ‘After’, after all, is a preposition that, like most prepositions, has a variety of different uses.

“After my own heart” could, for instance, have a sinister intent, as with hounds after a fox. The writer in pursuit of the reader’s heart. But it doesn’t mean that. It means “after the nature of; according to”, a usage going back to the Bible (“There is therefore now no condemnation to them which are in Christ Jesus, who walk not after the flesh, but after the Spirit”, Romans 8:1-2) – though the specific usage of “a man after his own heart” isn’t recorded until 1882, when it appears in, of all places, The Guardian, attributed to one G. Smith.

But the other meanings or uses of ‘after’ hover around the word. ‘After’, too, in the sense of “after the manner of; in imitation of”, as it’s used in art history – for example, Picasso’s The Maids of Honor (Las Meninas, after Velázquez). I remember a novel called After Breathless, by Jennifer Potter, that I read simply because it was inspired by A Bout de Souffle, my favourite film. “After my own heart” as critical interrogation.

And then the word ‘own’ in the phrase, too: after my own heart. It’s a phrase that is deeply, reverberantly embedded in the language from which it grows. It’s a phrase to conjure with. It’s an idiom, in other words.

My final brief thought, and again someone has probably written on this, but what exactly is the relationship between idiom and cliché? Does an idiom have to pass through the state of being a cliché before it can achieve this linguistic apotheosis? Is an idiom merely a cliché that has freed itself of the negative connotations of overuse – overuse with a single meaning – to allow itself to take on other meanings. Because that’s the problem with clichés, isn’t it? Not that they’re overfamiliar as phrases – as signifiers – but because their overuse has obliterated the meaning the phrase intends. The site of meaning has been rubbed raw.

Out of photographs into words: Nathalie Legér’s Exposition, Barthes and the mother-child photograph

Nathalie Léger’s Exposition is the first in a loose trilogy of books published in French between 2008 and 2018. Formally they mix essay, criticism and memoir. In each of them Léger focuses on the work of a woman engaged in making art in some way either provocative or running counter to the prevailing cultural mood, and each of them pulls back from that woman to consider the art form in which they’re working, and then to reverse, as it were, into the author’s own life.

Nathalie Léger’s Exposition is the first in a loose trilogy of books published in French between 2008 and 2018. Formally they mix essay, criticism and memoir. In each of them Léger focuses on the work of a woman engaged in making art in some way either provocative or running counter to the prevailing cultural mood, and each of them pulls back from that woman to consider the art form in which they’re working, and then to reverse, as it were, into the author’s own life.

Although Exposition (2008) opens this trilogy, it was not the first to appear in English. That was Suite for Barbara Loden (2012), about the film actor and director of that name. (All three books are or will be published in the UK by Les Fugitives. I wrote about Barbara Loden here.) Loden’s sole film as writer and director, the American new wave landmark Wanda, remains a cult favourite, though hopefully she will in future be better known for that than for being Elia Kazan’s second wife.

The third book, The White Dress (2018), treats Italian performance artist Pippa Bacca, who in 2008 hitchhiked from Milan to Jerusalem wearing in a wedding dress to promote world peace; she was raped and murdered in Turkey.

(The White Dress is forthcoming from Les Fugitives and I will be talking with Léger about it at the Institut Français in May.)

What follows is some thoughts on Exposition, following an event last week at The Photographers’ Gallery, at which I discussed the book with its translator, Amanda DeMarco.

Exposition takes as its subject the Countess de Castiglione, Virginia Odioni (1837-1899), an Italian aristocrat who took Paris by storm in the 1850s – though see how young she still was! – and was briefly mistress of the French Emperor. (Again, how young.) She was famed for her beauty and her narcissism, and was later rejected by the court, and ended her life more or less in squalor. Through all this she was obsessed with having her photograph taken, returning again and again to the same society studio, in good times and bad, for elaborate photographs – in costume, role-playing with props and accessories – taken to her own specification. (Shades of Cindy Sherman, as Léger notes in her book, and also of selfie-culture, though Léger doesn’t mention that: the iPhone 4 with front-facing camera wasn’t released until 2010, two years after Exposition‘s original publication.)

Exposition is partly a book about ideas of beauty, then, and partly about photography. It pays homage to classics of the genre such as Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida, without particularly seeking to insert itself into that genealogy. Léger turns away from Castiglione to write about photography, turns away from photography to write about writing, turns away from writing to write about herself – and her mother.

This aversion to straightforward narrative is played out through Léger’s loyalty to the fragment as form. She constructs her books from island-paragraphs that float unmoored on the white space of the page, with little attempt to make meaning or argument flow between them. You have to hop from one to the next. Which is not to say that there is no order to what is presented; the links are there to be made by the reader. What narrative flow there is works slowly, and at depth. Continue reading

Penguin mini-books: pocketing the canon

I doubt I’m alone among British readers in having something of a special relationship with Penguin Books. I doubt I was the only person who felt betrayed by its merger, in 2013, with Random House. Penguin was, I felt, part of my cultural birthright, and it was not in Penguin’s gift to get into bed with another publisher, no matter how powerful or prestigious, no more than it would be for the BBC to merge with Sky.

I doubt I’m alone among British readers in having something of a special relationship with Penguin Books. I doubt I was the only person who felt betrayed by its merger, in 2013, with Random House. Penguin was, I felt, part of my cultural birthright, and it was not in Penguin’s gift to get into bed with another publisher, no matter how powerful or prestigious, no more than it would be for the BBC to merge with Sky.

Certainly, Penguin’s continued status as something like the country’s national publisher might well be down to its track record in simply producing excellent books, but it is surely also down to its careful stewardship of its own brand. One way it does this is through the production, every now and then, of an eye-catching series of miniature or pocket-sized books, the latest of which is a series of 50 “small-form paperbacks” published this month as Penguin Moderns, and priced at a modest £1 each.

I say “backlist”, as if the likes of Samuel Beckett, Kathy Acker and Clarice Lispector are “Penguin authors” in the way that, say, Ted Hughes is a “Faber author”. Or, for that matter, F Scott Fitzgerald, Mary Wollstonecraft or Marcus Aurelius. Penguin started out as a reprint publisher, after all, rather than the commissioner of original material, and it is on its classics lists that its reputation primarily rests.

It’s easy to see how, for someone of my generation or older, Penguin felt like a part of my inheritance. When I was a teenager, Young Adult fiction didn’t exist as a category, so when I was finished with children’s books I moved not onto contemporary novels, but onto classics (Dickens, Wilkie Collins) and modern classics (Kerouac and Orwell), all but all of them in either the orange or eau-de-nil spines of Penguin.

Nowadays plenty of publishers have a ‘classics’ imprint – or market books as such, as if that were the same thing. But Penguin is still the classics publisher par excellence, and keeping people buying classics has got to be an interesting challenge for a publisher, particularly those books that aren’t on the school or university syllabuses, and that haven’t dropped onto Andrew Davies’s desk for prestige film or television adaptation. These series of mini-books are part of how Penguin have done this. Continue reading

Today’s sermon: Blue, blue, blue, blue

I somehow seem to have acquired a number of books about the colour blue. When Vintage added to these with their reissue of Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, I decided I just had to write something about them. So, a piece about books about blue, by someone with, actually, no interest in the colour blue at all.

Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, originally published in the US in 2009 and only now appearing in the UK, thanks to Jonathan Cape, joins a small collection of books I seem to have acquired, without really trying, on the subject of the colour blue. Nelson’s book might best be described as an essay in the form of prose-poetic fragments; its tone is set from the first line, which runs: “Suppose I was to begin by saying that I had fallen in love with a color”. What follows are ruminations on Nelson’s relationship with the colour blue; more critical explorations of why this colour might have a power over us that red, for instance, or green don’t have; and brief back-slips into memoir that exhibit the same jagged candour as The Argonauts (2015).

The other books in my micro-collection are William Gass’s On Being Blue, Derek Jarman’s Blue, and Blue Mythologies by Carol Mavor. It may be chance that these particular books have come into my possession (I have no particular interest in the colour, myself) but it is surely not chance that all these books were written about blue, rather than any other colour. Nelson is well aware of the anomaly. “It does not really bother me that half the adults in the Western world also love blue”, she writes, “or that every dozen years or so someone feels compelled to write a book about it.”

In defence of the comma splice: Katie Kitamura’s A Separation

I’d been planning to write about the comma splice for a while. Reading Katie Kitamura’s novel A Separation (Clerkenwell Press), I made a note that it would be a useful book to quote from, as it uses the device a lot. Then I read, yesterday, that Lionel Shriver had picked up on the same thing in her review of the novel in the FT, in order to criticise it. She writes:

Kitamura’s relentless joining of complete sentences with commas is grating, giving the text the look of weak secondary-school essays. One example of hundreds: “This was hardly surprising, the bar did not seem to be set especially high, Stefano, for all his merits, did not seem like an intellectual force.” What do those errant commas achieve? For this reader, irritation, distraction and impatience. Liberal deployment of full stops would have left the prose cleaner, clearer and crisper, while sharpening the voice.

Shriver does acknowledge that this is a genuine stylistic choice on the part of Kitamura, and that the first-person voice she chooses for her (unnamed) narrator is “otherwise strong”.

I think the use of the comma splice is highly effective, and key to the success of the novel. Before I say why, a general remark about writing and grammar.

Insofar as there are grammatical rules, the comma splice is an error, a joining together of syntactic units that would be better served as being treated as full sentences, i.e. separated by full stops. As I tell my students – as teachers everywhere tell their students – rules are there to be broken, but I want to know that you know you’re breaking the rule, and ideally I want to know why. That is, I want to be confident that your comma splices are there for a clear and definite stylistic reason, and not because you think what you’re writing is ‘correct’ English, or never knew that it wasn’t. (All comments about the validity of such a concept as ‘correct English’ should be saved for the end of this post, by which time hopefully they will be forgotten.)

In Kitamura, then, the comma splices are there for a definite reason, which is to do with the presentation of the narrator’s state of mind. A Separation is a first person narrative, that starts in the past tense:

It began with a telephone call from Isabella. She wanted to know where Christopher was, and I was put in the awkward position of having to tell her that I didn’t know.

Today’s sermon: On an island

An island presents an ideal conjunction of the three states of matter: land, sea and sky; solid, liquid, gas. The world rarely displays itself so uncomplicatedly to human understanding. The same tripartite division is available to anyone standing on any coastline: here is the land, there is the sea and there, in the distance, is the sky, but the arrangement of horizontal strata is too basic, too much like a cream slice.

An island offers a more complete and fascinating series of meetings between the three states, a different boundary ever way you look. There is land and sky, there is sky and sea, here sea and land.

Each of the three states makes it available to the inhabitant of the island. Climb the island’s mountain, and you might find yourself enveloped in cloud; comb the beach and discover the daily exchange of a coastal economy.

On this particular island that border is patrolled by up to 200 grey or Atlantic seals. Bobbing in the water they act as sentinels, curious, and ready to follow a walking human or come in closer to inspect their credentials, lifting themselves on the swell to peer, then dipping back down to show the sleek line of a back. Out on the rocks at low tide, however, the change is huge enough to be laughable. What were doglike in behaviour, roughly human in scale, so far as you could tell – you can see how the myth of the selkie arose; these creatures are seductive in their mastery of their element – are now preposterous in their camp torpor. Lolling on exposed rocks like Roman senators at feast, they pose and groan like Renoir odalisques, brushing a flipper over their whiskered snouts, clapping their tail flippers delicately together – something strangely coquettish about that laying together of the flippers, at once demure, like legs pressed resolutely together, and sexual, as of the female genitalia: hidden and on show at the same time. I have perhaps been on this island too long. Continue reading

In praise of spoilable books: the books that one must not speak of

Among other things, I am a book reviewer. In other words, I spoil books for a living. I’ve been thinking about this aspect of writing – or otherwise communicating – about books recently, prompted by my reading of a novel, Sergio Y., by Alexandre Vidal Porto. I had been been sent it by the publisher, and for a few weeks it had sat on the shelf in my study where these free books sit. I file the press releases in a separate folder, without looking at them; usually I give at least a glance at the front and back covers, and at the first page. Opening the post often happens when I’m in the middle of writing something quite different, and I don’t want to be distracted. That particular to-be-read shelf functions in a specialised version of the usual to-be-read shelves: the books sit there, patiently, quietly advertising themselves by their spines, and I glance at them as I pass, occasionally pull one out, glance at it or flick through it, put it back. Who knows what combination of memory, intuition and hope makes one reach for a particular book at a particular time. It would be lovely it there was something magical about it.

Two days ago, I reached for Sergio Y. Continue reading

Javier Marías: Enemy of le mot juste, master of or

There’s a line near the beginning of Javier Marías’s new novel, Thus Bad Begins, that made me smile.

Muriel was very rarely confused, on the contrary, he prided himself on being very precise, although sometimes, in his search for precision, he did have a tendency to ramble.

The narrator, Juan de Veres, is describing his employer, Eduardo Muriel, but he could just as easily be describing Marías’s own writing style, which is dilatory in the extreme: it moves forward incredibly slowly, in long, involved paragraphs, trying out words, phrases and descriptions in order to see which best approaches the behaviour being described. It’s not rambling as such, nothing so random or evasive: the prose seems to move through language in circles, returning and returning to particular key terms (best exemplified by the repeated use of the words in the volume titles of his magnificent trilogy, Your Face Tomorrow: Fever, Spear, Dance, Dream, Poison, Shadow, Farewell) ; the only forward motion is, paradoxically, inwards, deeper into the psychology of the characters. The prose has great psychological penetration.

One of the ways that Marías achieves this is through comma splices, as in the sentence quoted above. Another is through the simple word ‘or’. When Marías uses ‘or’, it is not to offer logical alternatives at the level of plot, but at the level of the sentence, even at the level of the word. No word is precise enough for Marías. Or rather, words are precise, in their way, but human behaviour is so complex and ambiguous that it might take a number of alternative words to successfully describe how a person is, or behaves.

Here is a passage a few pages further on in the book:

‘What on earth has he been told about this dubious friend of his – or, rather, this friend who suddenly appears to be dubious – what can he have said or done?’ I wondered, or thought. ‘After half a life of utter clarity.’ Or perhaps that isn’t what I thought, but only how I remember it, now that I’m no longer young and am more or less the same age as Muriel was then or perhaps older.

Six ors in that little passage; two perhapses; one rather. Sometimes the or is doing a simple job, as in the last one, when the protagonist reassesses his age compared to that of his employer at the time he remembers him; sometimes it offers basic alternatives – said or done; sometimes it is an attempt to improve on the clarity of thought or expression, as in the first line.

My favourite, however, and the one I consider most characteristic of this writer I love, is the one that offers a distinction between wondered and thought. Plain synonyms, in most writers’ hands, but not for Marías. He is the master of the fine distinction, that is never fine enough. Rather than describing a character in one way, and basta!, he offers two, three or four alternatives, with the definite implication that none of them are right.

As I writer, sometimes I use a thesaurus. Like many writers I usually end up back with the word I started with. But, probably like most writers, what I’m looking for when I pick the thesaurus up, is the most precise words, le mot juste. Marías, you’d think, uses the thesaurus not to find a better word to replace the one he has, but others to add to it.

I love this style, so much so that I tried to copy it in a story I wrote. Imitation intended, at least, as sincere flattery. The story is The Story I’m Thinking Of, which you can read on the White Review site.

Today’s sermon: In case you’d forgotten what reading has done to you – Jack Robinson’s By the Same Author

By the Same Author is a thin book by a thinner writer. The book itself is a collection of 39 paragraphs spread over 43 pages – plenty of white space; it doesn’t take much more than an hour to read, but that just means you’ll want to reread it – you’ll want there to be more of it. I intend to not lose sight of; it won’t get relegated to the alphabetised shelves, where – it’s so thin – it would end up being squished right out of existence by Marilynne Robinson and David Rose, neither of whom are particularly doorstops.

To call the author thinner still is a nod to those familiar with their Dashiell Hammett. The author biog tells us that Robinson has “also written as Jennie Walker… and Charles Boyle”, Boyle being the man behind CB Editions, which publishes this slip of a book, as well as all manner of interesting material. He is a publisher of the old type, unbeholden to anything but his own taste. The previous book by Robinson that I’ve read is Recessional (2009), a barely bigger scrapbook of rants and screeds against political austerity and our conservative country. I don’t like it half as much as this one.

In the first paragraph of By the Same Author we learn the title of a book, XXX, which the narrator (Robinson, for the sake of argument) has recommended to him (for the sake of argument) by a waiter after he, the waiter, runs up to return a different book by the same author which he, Robinson, had left on a café table. One of those moments of connection. (Eric turns up again, quite a lot. Expand By the Same Author along certain lines, and their relationship would end up something like that of Lars and W in the Spurious trilogy.)

Over the page, in the second paragraph, we learn the name of the writer: T.S. Nyman. The book, then, is about Nyman, and XXX, and Robinson’s relationship to her and it. There is no narrative, no development, just an accumulation of reflections on a writer and her oeuvre. For example: a coach trip to Cardiff where Robinson sits sat next a girl reading XXX, and they spend the entire journey excitedly reciting it to each other; watching Nyman give readings, terribly, on YouTube; a glance at her author biography; an event in Paris billed as an appearance by Nyman that turns out to be a terrible solo male contemporary dancer. Continue reading

Today’s sermon: What is art for? A response, in part, to Raymond Tallis’s Summers of Discontent

To Waterstones Piccadilly on Wednesday night to hear and join a debate on ‘the purpose of the arts today’, based on Raymond Tallis’s book Summers of Discontent – essentially a careful selection of his previous writings by writer and gallerist Julian Spalding. This isn’t one of those socio-political treatises that tries to explain why we should go on pouring so many millions a year into the Royal Opera House, or why the Arts Council budget should be slashed or increased, but rather a philosophical discussion of what the art encounter, whether it be literature, music or theatre, can give us, as existential, post-religious human beings.

Tallis’s premise is that we as humans suffer a ‘wound’ in the present tense of our consciousness, such that we can never be fully present in our lives, but are always late to our own experiences. Art, he says, can help with this by showing how disparate formal elements can be integrated into one unified work; it offers both a model for how to do the same with our own scattered and disparate memories, thoughts, impulses and anticipations, and also a hypothetical space in which to do that work. It gives us a here and a now to be present in.

I was asked, along with philosopher Roger Scruton and classicist Stephen Johnson, to respond to Tallis and Spalding’s remarks, before the debate was opened to the floor – my ‘role’ being that of novelist, and of novelist about ‘the arts’. My no doubt disjointed comments amounted to some of what follows:

that I fully approved of the notion of the wound in the present tense, and of art’s ability to – partially, temporarily – heal or alleviate it, and of doing so by modelling and facilitating formal integration (where, as Tallis points out, ‘form’ is taken to mean the inside, rather than outside shape of things), but that this is surely an ideal, rather than a usual occurrence.

Tallis was starting from a position where he talked about “art when it is at its best and we are at our most connected” – when, to my mind, most of the time neither of those things is true. (In fact there’s a lovely description in his book of listening to a Haydn Mass “while the squeaky windscreen wipers are battling with rain adding its own percussion on the car roof” – and that is think is how we experience most art.)

As a novelist, I want my writing to be at its best, and my readership at its most connected, always, but as a novelist who writes particularly about the arts (the contemporary art world, in Randall, and the world of pop music in my new book), what I’m interested in is the ordinary failings of poorly connected people responding to less than great art – but who, crucially, are no less committed to that project of arriving at a place of integration and connectedness.

I gave the example of seeing Fleetwood Mac at the 02, a pretty good gig in a dismal setting by a band of which I’m not particularly a fan. (I love the album Tusk to bits, but can do without the rest of their stuff.) I responded variously to the music, leaping up at the songs I liked, nodding along to the rest, but what really got me was the response of the other audience members. There were men in the 60s, podgy and balding, as I’ll doubtless be at that age, standing there agog on the concrete steps, hundreds of metres away from their idols, faces slack and eyes streaming with tears. Continue reading