Tagged: Andre Gide

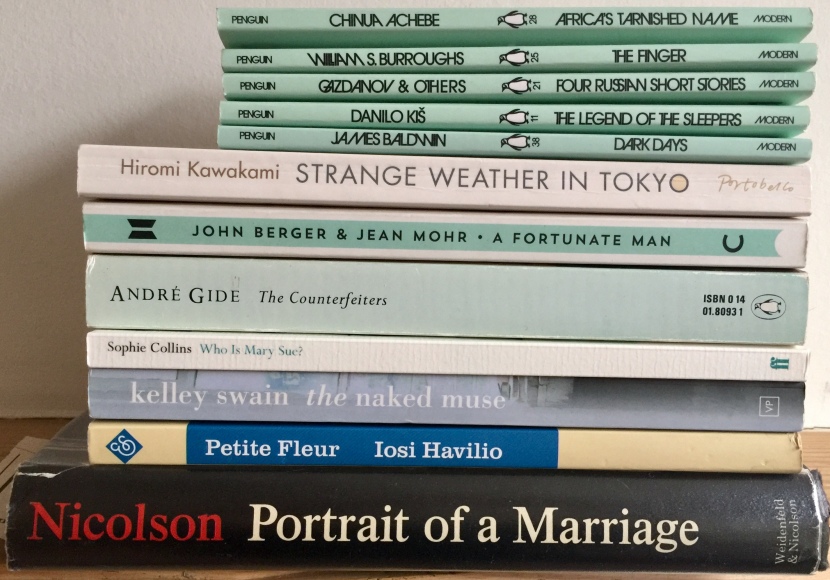

February reading: Gide, Havilio, Berger, Kawakami, Swain, Collins, Nicolson and Sackville-West

I turned to The Counterfeiters this month after rereading and thoroughly enjoying Gide’s Strait is the Gate, which I’d read when a teenager, along with his lyrical and prophetic The Fruits of the Earth. I’d also read his more straightforwardly existentialist The Vatican Cellars, but for some reason had never got around to this, his other longer novel. I preferred Strait is the Gate, I have to say, for its gem-like precision. Nothing is wasted; everything is focused on the tragedy of the novella’s central relationship. The Counterfeiters (translated again by Dorothy Bussy) is one of those novels that must have been terribly shocking when it came out, for its depiction of nihilistic young French men talking about setting up avant garde literary journals, and probably being homosexual. Shocking – or thrilling, if you get a thrill from the idea of other people being shocked by what you read.

None of that really carries over today. It reads like the sort of literary ‘group novel’ that crops up every now and then. I remember one, by an author I know can’t remember, called All the Sad Young Literary Men, which is a great title absolutely not in need of a novel to justify it. Nor, really, is there any shock to the aesthetic frisson of Gide breaking the fourth wall to talk directly to the reader about his characters, and his confusion about where the novel is going. Admittedly the frisson is greater than, or different to, that in, for example, Tristram Shandy, because The Counterfeiters is not “Shandy-esque”: it is by and large a realist novel, and not interested in playing postmodern games, so the gentle looks-to-camera do give something of a jolt. It took me a couple of weeks to read the book, largely at bedtime, and I admit that I rather lost track of who all the disaffected young men and their decadent older friends were, and got them all confused with each other, meaning that the moral impact of the narrative was lost on me. But the Wildean dialogue was enough to keep me amused.

The last book I read in the month was Petite Fleur, by Iosi Havilio, translated by Lorna Scott Fox (And Other Stories, proof copy, for which much thanks!). This is a book short enough to read in one day, on the commute to and from work – though admittedly snowy delays did rather help with the logistics of that. This Argentinian novel carries comparisons on its cover to Tolstoy and César Aira, and the second of those is spot-on in terms of its gleeful, light-as-air ludicrousness – that bottoms out into terrible clarity just when you hope it won’t. I shan’t say much about the plot, as its pleasures come through its masterful sequences of bluffs, feints and double-bluffs, and these deserve not to be spoiled. I’ll say, though, that while it took me a fair few attempts to learn how to enjoy Aira’s output (by taking each book as a part of a broad, diffuse project, rather than a fully independent entity) Havilio manages to build that bold sense of randomness into this one book. The Tolstoy comparison is more uncertain. You’ll see why it’s mentioned when you read the book, but really we’re closer to Gogol than Tolstoy, in the book’s full-pelt playfulness with what readers think novels should be. I realised ten pages in that I’d tried to read it once before, and given up on it. I can see now that I must have been distracted. Elements that I had found merely confusing, before, now carried the full charge of the absurd. It’s a shame, too, about the title, which again makes sense when you read the book, but is hardly representative, and is frankly a bit shit. If Fever Dream hadn’t already been taken, you could call it Fever Dream. I preferred this to Schweblin’s book. Continue reading

January reading: Gide, Riley, Hoban, Thorpe, Melo, etc…

My month’s reading began with Russell Hoban’s Pilgermann and ended with First Love, by Gwendoline Riley, read in a day, started on the train to work, and finished – nearly – on the train home. I read the last five pages leaning over the kitchen counter, eating hobnobs. If it had been light I would happily have stood out on the street to finish it. How does it end? Unexpectedly, desultorily, off-handedly, as it proceeds. It is, I think, the second Riley I’ve read. It’s excellent: a sketch (not a portrait) of a toxic marriage, with the narrator’s other relationships – ranging from also toxic to just failing to simply meh – doodled in the margins. Looking at it now I feel there’s a real risk that, for all my pleasurable immersion in its slantwise take on life, it will evaporate from my mind, as, indeed has the other Riley I’ve read, Joshua Spassky. (Maybe I’ve also read Opposing Positions. I’ve definitely got it. This isn’t looking good.) So, here’s me telling to re-read First Love in five years’ time. Item: “a small, poxed mirror”. Item: “We walked up to the shops, into the throat of the wind.” Item: “Outside the sunset abetted one last queer revival of light.” Item: the handful of walnuts; those final, vituperative rants. If some novels are the equivalent of a nice cup of tea, this book is a cup of tea, spilled. Deliberately, and pointedly.

Hoban couldn’t have been more different. It’s as much an outlier in the Hoban oeuvre as Riddley Walker, which it follows. A middle-aged reel through the Middle Ages, it follows the man (and owl) Pilgermann through some kind of life, some kind of afterlife. It lifts itself into operatic riffs on various religious preoccupations; it’s got walking corpses and terrible battles and Jewish folklore. It starts better than it finishes, though it starts brilliantly. The idea of picking it up again, now, four weeks on, to work out what was going on in it, seems rather too tiring. I prefer his later, more obviously comic novels, that seem to carry themselves more lightly.

Black Waltz, by Patrícia Melo, translated from the Portuguese by Clifford E Landers, is a re-read. I’d been meaning to try it again. It’s a story of a man – a successful international conductor – unhinged by jealousy. With no apparent reason apart from his own delirium, he he decides that his younger wife, a violinist, is being unfaithful to him. He ends up losing much more than her. It’s smoothly gripping, and effectively guts the reader at crucial moments. It reminded me of the early standalone Elena Ferrante novels, especially Days of Abandonment.

My Name is Lucy Barton, by Elizabeth Strout. Well: it’s exquisitely written – but I wasn’t fully taken in. Something about the reticence, the distance with which emotions are held, and for what purpose, meant it didn’t work its magic on me as it has on others. I wonder if it’s something to do with American reticence, which has a slightly different tenor to British, or English, reticence. Perhaps Americans see it as less of an inherent national trait, puritanism aside, and so it tastes that bit more delicious to an American palate.

Seven Brief Lessons on Physics – a Christmas present from my sister – was a bit of a frustration. I mean, how many times do I have to read accounts of quantum physics, black holes and the rest of them, before I actually understand them? I don’t think it will ever happen. (It happened, once, briefly, watching Michael Frayn’s Copenhagen. I got it, I really did – with the way the characters walked across the stage representing the movement of quarks or whatever they are – but I lost it the moment I left the theatre.) It doesn’t help that Carlo Rovelli uses some hokey metaphors to try to explain his science. When he says that the elementary particles “combine together to infinity like the letters of a cosmic alphabet to tell the immense history of galaxies, of the innumerable stars, of sunlight, of mountains…” and so on, I just can’t see how that helps. That’s not how letters work, really, and I can’t imagine that that’s how elementary particles work either: placed in sequence to form clusters as much made up with reference to the letters that aren’t there as to those that are, these clusters then being themselves arranged in particular sequences, so as to suggest meaning. That’s how the universe is made? No, it’s not.

River (by Esther Kinsky, translated by Iain Galbraith) and Sight (by Jessie Greengrass) are there because of reviews, still forthcoming. An Account of the Decline of the Great Auk… was homework for that review. (Review links added, to The Guardian and The White Review)

Flight was (re)read for the MA Creative Writing module I’ll be teaching this semester. It’s a great blokey literary thriller, a little too on-the-nose in the way it looks for flight metaphors, but agreeably credible in its blend of mystery and violence, and its slow unfolding of human relations, and evocative in its description of the remote Scottish coastline.

Heinrich Böll’s The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum (trans Leila Vennewitz) was read as a palette cleanser, because it was so short. But, for a short book, it’s dicey to read, and not just because this old Penguin paperback is going at the spine. At this distance (it was written in 1974) its twin themes of sensationalist tabloid journalism and the furore around the Red Army Faction terrorist group don’t seem to carry equal weight. The journalism stuff seems heavy-handed, but also naïve by comparison with the way news organisations treat individual privacy today, while the terrorism, so much meatier as a theme, is treated less thoroughly. The documentary style is interesting, certainly, and it’s made me want to keep exploring Böll. His stories, apparently, are superb.

Another short book I (re)read in a day is André Gide’s Strait is the Gate, translated by Dorothy Bussy, who features in Kate Briggs’s fascinating book about translation, This Little Art. Picked up because its title accidentally mirrors the title of my current work in progress, it astonished me again with the pure music of its prose, and the aching passion of its story, melodramatic and melancholy at the same time. It’s the story of a young love destroyed by excess religious sense, that sees heaven only in self-denial. It made we well up, and as good as cry, twice. If you read Gide in French as a schoolchild (probably La Symphonie Pastorale) it might be time to pick him up again. I want to go on straight to another of his books. I’ll see what I have. This, though, is a sublime little book.

The stories (Chris Power, M John Harrison, Bridget Penney, in a lovely old Polygon edition) I’ve been dipping into and enjoying. I may write about them next month.

Also read, but not pictured: The Language of Kindness, the forthcoming nursing memoir written by my colleage at St Marys, Twickenham, Christie Watson. That made me well up more times than I care to remember. A stonkingly human book, brilliantly pitched and controlled.

Goodbye, January.

Today’s sermon: Life eludes logic

The want of logic annoys. Too much logic bores. Life eludes logic, and everything that logic alone constructs remains artificial and forced. Therefore is a word the poet must not know, which exists only in the mind.

Andre Gide, The Journals.

Means of enticement and instigation to work: Writing tips from André Gide

All this from Gide’s journals, the year 1893, when he was 24 years old.

Means of enticement and instigation to work.

1. Intellectual means:

(a) The idea of imminent death.

(b) Emulation; precise consciousness of one’s period and of the production of others.

(c) Artificial sense of one’s age; emulation through comparison with the biographies of great men.

(d) Contemplation of the hard work of the poor; only intense work can excuse my wealth in my own eyes. Wealth considered solely as a permission to work freely.

(e) Comparison of today’s work with yesterday’s. Then take as a standard the day on which you worked the most and convince yourself by this false reasoning: nothing prevents me from working as much today.

(f) Reading of second-rate or definitely bad works; recognize the enemy and exaggerate the danger. Let your hatred of them urge you to work. (Powerful means, but more dangerous than emulation.)

2. Physical means (all doubtful):

(a) Eat little. Continue reading