Category: Writing

London Consequences 2 – a collaborative novel

Announcing a new and very exciting collaborative writing project: London Consequences 2.

London Consequences 2 is a collaborative novel being written from September to December 2022 by a collection of amazing contemporary writers (see below!). It is organised and curated by David Collard, Jonathan Gibbs and Michael Hughes, and is a creative response and homage to a little-known but very interesting book published 50 years ago called, yes, London Consequences.

London Consequences was a collaborative novel written for the 1972 Festivals of Britain and edited by Margaret Drabble and BS Johnson. Drabble and Johnson co-wrote an opening chapter, and then passed the manuscript on to a series of 18 writers (including Melvyn Bragg, Olivia Manning and Eva Figes) who each wrote one chapter before passing it on, until it returned to the editors, who co-wrote the closing chapter. The published book listed the contributing novelists, but each chapter was anonymous, giving readers the fun parlour-game challenge of trying to work out who wrote what. (There was a £100 reward for whoever could successfully do this – as yet we have no idea if this was collected!)

Original writers:

Paul Ableman

John Bowen

Melvyn Bragg

Vincent Brome

Peter Buckman

Alan Burns

Barry Cole

Eva Figes

Gillian Freeman

Jane Gaskell

Wilson Harris

Rayner Heppenstall

Olivia Manning

Adrian Mitchell

Julian Mitchell

Andrea Newman

Piers Paul Read

Stefan Themerson

The original novel features a middle-class London couple, Anthony (a journalist) and his wife Judith (a mother and housewife) on a single day – Easter Sunday, 1971 – as they navigate the capital, and their relationship with each other. It was published in 1972 by the Greater London Arts Association, with a cover price of 65p.

The idea for this new project came about in a strange and serendipitous way. In April 2022 I turned 50, and Michael Hughes gave me as a present a copy of London Consequences, which I read and very much enjoyed. I tweeted that it would be a fun idea to do a contemporary version, to which David Collard, who knew the original, responded by throwing down the gauntlet. We should do it, he said.

Continue reading‘A Prolonged Kiss’ shortlisted for the Sunday Times Audible Short Story Award 2021

In very exciting news my short story ‘A Prolonged Kiss’ reached the shortlist for the Sunday Times Audible Short Story Award 2021. This is the world’s biggest and most prestigious prize for an English-language single short story, with the winner scooping a slightly surreal £30,000 prize.

The shortlist features some amazing writers published in some fantastic outlets.

Rabih Alameddine – ‘The July War’ (Paris Review)

Susan Choi – ‘Flashlight’ (The New Yorker)

Laura Demers – ‘Sleeping Beauty’ (Granta)

Elizabeth McCracken – ‘The Irish Wedding’ (The Atlantic)

Rachael Fulton – ‘Call’

and ‘A Prolonged Kiss’ by me.

On Thursday 1st July the London Library hosted an online event with the six shortlisted writers and judges David Mitchell and Andrew Holgate which you can watch here.

So I feel this is a success I share with The Lonely Crowd, the indie journal where my story was published, thanks to its editor John Lavin. The story was published in Issue 12 of the journal, which you can buy here.

Here is the 15-strong longlist in full:

Rabih Alameddine – ‘The July War’ (Paris Review, subscribers only)

Jamel Brinkley – ‘Comfort’ (Ploughshares, subscribers)

Susan Choi – ‘Flashlight’ (The New Yorker, subscribers)

Susannah Dickey – ‘Stuffed Peppers’

Laura Demers – ‘Sleeping Beauty’ (Granta online, free to read)

Louise Erdrich – ‘Oil of Emu’

Rachael Fulton – ‘Call’

Jonathan Gibbs – ‘A Prolonged Kiss’ (The Lonely Crowd, purchase here)

Allegra Goodman – ‘A Challenge You Have Overcome’ (The New Yorker, subscribers)

Rachel Heng – ‘Kirpal’

Daniel Mason – ‘A Case Study’

Elizabeth McCracken – ‘The Irish Wedding’ (The Atlantic, free to read)

Gráinne Murphy – ‘Further West’

Adam Nicolson – ‘The Fearful Summer’ (Granta 152, subscribers)

Mark Jude Poirier – ‘This Is Not How Good People Die’ (Subtropics)

This is obviously a huge boost, and my thanks go out to the judges, Yiyun Li, David Mitchell, Curtis Sittenfeld, Romesh Gunesekera and Andrew Holgate.

The winner was announced on July 8, 2021, and it was ‘Flashlight’ by Susan Choi, which I absolutely can’t argue with as a choice. It’s a phenomenally strong story, wonderfully shaped, with great scene-writing and dialogue, and some feather-light touches of brilliance in the plotting. I read it, frankly, in awe and envy, and I love it!

‘Spring Journal’ a year on: anniversary and review

On Friday 19th March 2021 it will be one calendar year since I lay on a sofa, phone in hand, and had the idle thought that one could tweet about the impending coronavirus pandemic, and the lockdown that had just started, in the form of a mash-up with / homage to / pastiche of Louis MacNeice’s ‘Autumn Journal’. I created a new account (that’s one of the things I love about Twitter as a creative platform; you can put ideas into action with no planning or forethought), grabbed my MacNeice Selected Poems paperback from the shelves, to copy those famous opening lines, and posted two tweets, that same evening. Here they are:

And here are the corresponding opening lines from MacNeice:

Close and slow, summer is ending in Hampshire,

Ebbing away down ramps of shaven lawn where close-clipped yew

Insulates the lives of retired generals and admirals

And the spyglasses hung in the hall and the prayer-books ready in the pew

And August going out to the tin trumpets of nasturtiums

And the sunflowers’ Salvation Army blare of brass

And the spinster sitting in a deck-chair picking up stitches

Not raising her eyes to the noise of the ’planes that pass

I carried on Tweeting my version of MacNeice in sporadic bursts over the next few weeks (I particularly remember standing in the aisle at Sainsbury’s Tweeting about standing Tweeting in the aisle at Sainsbury’s) and maybe the whole thing would have fizzled out if David Collard hadn’t asked if would like to feature the poem on his online salon A Leap in the Dark, which ran on Friday and Saturday evenings right through lockdown, on Zoom. It was a typically generous offer, but David’s stroke of brilliance was to invite, or persuade, Northern Irish novelist and actor Michael Hughes to do the readings – a canto a week, starting in early April, and running through until I had matched MacNeice’s 24 cantos. Michael read the final canto as part of a full read-through of my poem on Friday 28th August.

As it happens, the anniversary of the poem’s inception coincides with the first review of the book of the poem, which was published by CB Editions in December, after a typically nimble quick turnaround by Charles Boyle.

Tristram Fane Saunders in the Times Literary Supplement starts by setting the poem against the responses from more famous names (Don Paterson, Paul Muldoon, Glyn Maxwell), and is generous in his estimation of how my poem measures up to its inspiration and model:

aiming somewhere halfway between cheap pastiche and serious homage, Gibbs hits his mark. He nails Autumn Journal’s casual, yawning metres and late-to-the-party rhymes, its balance of didacticism and doubt.

You can read the whole review here.

(And if you have the print copy of the paper, you can have the additional thrill of turning the page to find, recto to my review’s verso, a review by Michael Hughes himself, of Anatomy of a Killing, by Ian Cobain.)

This anniversary also coincides with the vigil for Sarah Everard and protest against male violence on Clapham Common, so appallingly handled by the Met Police, which I mention only to point out the obvious fact that the pandemic only brought to the surface frustrations and inequalities that had been brewing and burning for much longer. And that if it felt like the six months during which I wrote the poem happened to have given me material to bounce at MacNeice, as it were, as a sounding board, then that’s missing the point. Whenever this had happened, these things or something like them would have happened, because they’re always happening.

The lines that Charles Boyle chose to put on the back of his edition of ‘Spring Journal’ were these:

Too many are dead, but jobs are dying too, all over.

The virus reveals the flaw

In our way of living: the rich fly it around the planet

And dump it on the doorsteps of the poor.

And the fact that the murder of Sarah Everard, and the way it triggered deep-lying anger about structural misogyny in our society, seems to repeat what happened last year when the murder of George Floyd did the same for structural racism, only goes to show that we are stuck in a cycle. The anniversary puts us no further forward in the kind of world we want to live in, and nothing to show for the lesson of so many dead.

As I wrote in August, in the penultimate canto of my poem, addressing MacNeice:

And then autumn will come,

And I’ll pass back the baton,

Let you handle your natural season,

And I’ll be there waiting, in March, when you’re done.

For as long as there’s something vicious looming

Beyond the horizon, and just as long

As we keep on getting things hopelessly wrong,

We can keep this thing turning, from poem to poem.

‘Spring Journal’

On the evening of Thursday 19th March 2020 I was lying on the sofa, phone in hand, when I had the idea of tweeting about the coronavirus epidemic in short poetic bursts, inspired by Louis MacNeice’s wonderful long poem ‘Autumn Journal’. I have used Autumn Journal in teaching poetry to undergraduate students, offering it as an example of how to write outwards from the self, how to mix politics and the personal to give a sense of how you see the world. I could do that, I thought. I could do it on Twitter.

I created a new account, @SpringJournal, and wrote two tweets that evening, and six more the following day. Each tweet contained four lines of poetry in MacNeice’s “elastic kind of quatrain”, with rhymes coming on alternate lines, but the line lengths immensely variable, while still keeping to a sort of rhythm. As well as his easy, down-to-earth way of tackling his themes, one of the other things I love about MacNeice is his rhyming. He allows for awkwardness in his syntax, he can be occasionally leaden, but he uses rhyme to pay things off, like a bell till chiming to mark the end of a transaction.

I’ve written more about the poem – and am posting Cantos as they are completed and edited – on a page on this blog, here.

‘Knives Out’: character is plot, puke is truth. [Contains spoilers]

Last night I saw Knives Out, Rian Johnson’s wonderfully ripe murder mystery, that boasts a fine array of performances ranging from the judiciously over-the-top (Jamie Lee Curtis and Toni Colette) to the genuinely affecting (Ana de Armas, brilliant), as well as those that waver between the two. Here I’m thinking of Daniel Craig, whose atrocious southern accent disguises masterful detectorial insight, and Christopher Plummer as Harlan Thrombey, the bestselling crime writer whose apparent suicide on the night of his 85th birthday set the film in motion.

The cast is great, and the cinematography and direction workmanlike, but what struck me most of all was Johnson’s brilliantly contrived screenplay, which is a masterclass not just in mystery plotting – intricate enough to keep you guessing, and simple enough to make sense as flashback after flashback sends you zipping backwards and forwards in time – but in the logical construction of the central character’s emotional arc. What follows is an analysis of one aspect of this, and contains spoilers. It is intended only for people who have seen the film.

The key character point of Marta Cabrera, Harlan’s immigrant nurse, is that she is physiologically unable to tell a lie: if she lies, she throws up. There are four (in fact five) moments in the film when this fact is utilised. Two of them are essential to the plot, but all of them are central to our understanding of the nature of her character.

Character is plot, we are taught in creative writing books and classes, and this is a perfect instance of that. (In passing: I teach on an MA in novel-writing, and it’s a constant annoyance that so many examples that come up in discussion, from me as well as from the students, are from films, rather than novels. Why is this? I hope it’s simply because i) films are more memorable, as combining visual and verbal elements and ii) they are simpler, goddamit! All the same: I’m writing this post because I think the film can teach us a useful lesson in plotting.)

The first time we learn that Marta cannot lie without vomiting is the first time she is interviewed by Daniel Craig’s private investigator, Benoit Blanc. He probes her on her actions on the night of the party, and she dissembles, trying to hide something (we don’t know what at this point), and is then sick in a flower pot. Note that we don’t see the vomit.

There’s another minor repetition of this moment later in the film when Marta and her temporary partner-in-crime Ransom Thrombey (Harlan’s grandson, played by Chris Evans) are caught after a car chase with Craig’s Blanc and the other cops. Blanc, seemingly still believing her to be innocent, asks if Ransom forced her to drive. She says yes, though that’s not true, and surreptitiously spits up in a takeaway coffee cup. Again, we don’t see the vomit, and note that it’s a small bit of puke, for a small lie.

[The spoilers proper kick in here. Don’t read on if you haven’t seen the film. It’s worth it, I promise!] Continue reading

‘The Large Door’: where do you get your ideas?

My second novel, The Large Door, is published by Boiler House Press in April 2019. You can read more about it and sign up for updates here.

I remember exactly where I was when I had the idea for this book – or rather where the two ideas collided that made it possible. I was walking down the Mile End Road in Norwich after sitting in the library researching a conference paper on Brigid Brophy, a C20th British writer I had become a little obsessed by.

In the three years from 1962 to 1964 Brophy published three utterly brilliant short novels that I thought had rather slipped off the literary map: Flesh, The Finishing Touch and The Snow Ball. It was The Snow Ball that I was particularly enamoured of – a dark, sparkling and death-obsessed sex comedy set between midnight and dawn at a masked New Year’s Ball as close in spirit to C18th Vienna as Swinging London. It is unashamedly intelligent, psychologically acute and serious as hell about love and sex, all while whipping along the line of its narrative like a dancer in a drunken gavotte. Why didn’t anyone write books like that anymore, I thought, which naturally slipped far too quickly into the dangerous thought: hell, I will write a book like that!

And then, walking through the Norwich night, I realised I had the material to do it: a short story set over 24 hours at an academic conference, with an arch and unbiddable female protagonist very much in the vein of The Snow Ball‘s Anna. ‘Festschrift’ had been published by Susan Tomeselli in her excellent journal Gorse, and then picked by Nick Royle for one of his Salt Best British Short Stories anthologies, but expanding that 8,000-odd-word story to the length of a short novel shouldn’t be too much trouble, should it? The title, that had been lying around for about 20 years, and I also remember the moment when the decision to use it became absolutely fixed, when a particular sentence set itself down on the page.

During the time I’ve worked on the text, ripping it apart and building it back up, I’ve also been trying to read as much as possible of – and, in a way, to triangulate – three British writers who to my mind bestride the second half of the last century: Brophy, and the far better-known Iris Murdoch and Muriel Spark. I’ve read most of Brophy, and about half of Spark’s novels, and a third of Murdoch, and I find that, together, they map a set of approaches to writing fiction that I find irresistible. How to dive headfirst into your characters’ moral quandaries, like Murdoch, and wallow in them? Or how to hold them at arm’s length, like the divinely ambivalent Spark. In a sense, Brophy splits their difference: as involved in her characters as Murdoch, but able to dismiss them with a Sparkish turn of the wrist when need be.

The Large Door, in a sense, is the result of that reading, and thinking. Of course there are plenty of other concerns in the book, thoughts that occurred to me on the journey and got Hoovered up: how to make use of text message communication in prose fiction; how to make the mechanics of an academic conference (keynote speech, panel, workshop) remotely interesting; the desire to find a way to punch through the page of the novel – break the fourth wall, in theatrical terms – without resorting to the usual tired postmodern gestures.

But in essence the book is a serious attempt to do what Brophy did, time and time again, and Murdoch and Spark, in their different ways: put serious characters at the heart of a comedy. They all three of them write tragic-comedies, I suppose – comedies in their structure, in the artifice of their narrative devices, but tragedies in their temperament, in the way that you feel an abyss would open up under the characters if only they once looked down. I fell in love with Brophy’s Anna, as much as I’ve ever fallen for a fictional character, and that’s the challenge I set myself: to write a character that, for all their foibles and – say it! – unlikeableness, other people might fall in love with in turn.

New Twitter fiction: Death of a Cat

I spend too much time on Twitter. Sometimes I try to justify this by talking up, to myself if no one else, the creative possibilities of the website. In 2013 I wrote a story on it, one tweet per day on a dedicated account, over the course of the whole year. That story was called ‘J’, and was an experiment in ambient storytelling. I felt that I had identified the inherent obstacles the format threw up: that my one-a-day tweet would be drowned out in most people’s timelines by the wealth of competing information; that it would be difficult to sustain a narrative with 24 hours between each entry; that people wouldn’t necessarily see every tweet, and so would lost track of the storyline. My response to these was to give my story a simple overarching narrative that would allow individual tweets or runs of tweets to work within it, on a micro level, while the macro story would take care of itself. This was that ‘J’ would tell the story of one woman’s life, from cradle to grave, in that she was born on 1 January, and would die, aged 80-something, on 31 December. Some runs of tweets followed critical moments in her life in detail. Some jumped hopscotch through her experience. Sometimes things moved fast, sometimes things moved slow. On average J aged a year every four or five days.

You can read more about the idea behind the story here, and read the story in toto here.

Since then I have dabbled in a few other short-lived attempts at using Twitter creatively, but recently I had a new idea that uses Twitter threads to construct a single narrative story with different temporal and thematic strands. (Since then Twitter has changed the way it uses threads. I’m not entirely sure that this won’t spoil what I had planned, but the only to find out is to go ahead and see.) Since ‘J’, obviously, Twitter has also doubled its character count. The 140 character limit was integral to the style of that story, resulting in a story of 9,000 words. I’m not sure yet how I will deal with the new 280 limit.

Again, I’ve created a dedicated Twitter account to host the story, @deathofacat. That’s the title of the story: ‘Death of a Cat’. (Spoiler: a cat dies in it.) I will start it on 1 January 2018. Like ‘J’, it will be largely improvised, day by day. It won’t necessarily last a whole year. I’d love it if you followed the account.

Today’s sermon: Blue, blue, blue, blue

I somehow seem to have acquired a number of books about the colour blue. When Vintage added to these with their reissue of Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, I decided I just had to write something about them. So, a piece about books about blue, by someone with, actually, no interest in the colour blue at all.

Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, originally published in the US in 2009 and only now appearing in the UK, thanks to Jonathan Cape, joins a small collection of books I seem to have acquired, without really trying, on the subject of the colour blue. Nelson’s book might best be described as an essay in the form of prose-poetic fragments; its tone is set from the first line, which runs: “Suppose I was to begin by saying that I had fallen in love with a color”. What follows are ruminations on Nelson’s relationship with the colour blue; more critical explorations of why this colour might have a power over us that red, for instance, or green don’t have; and brief back-slips into memoir that exhibit the same jagged candour as The Argonauts (2015).

The other books in my micro-collection are William Gass’s On Being Blue, Derek Jarman’s Blue, and Blue Mythologies by Carol Mavor. It may be chance that these particular books have come into my possession (I have no particular interest in the colour, myself) but it is surely not chance that all these books were written about blue, rather than any other colour. Nelson is well aware of the anomaly. “It does not really bother me that half the adults in the Western world also love blue”, she writes, “or that every dozen years or so someone feels compelled to write a book about it.”

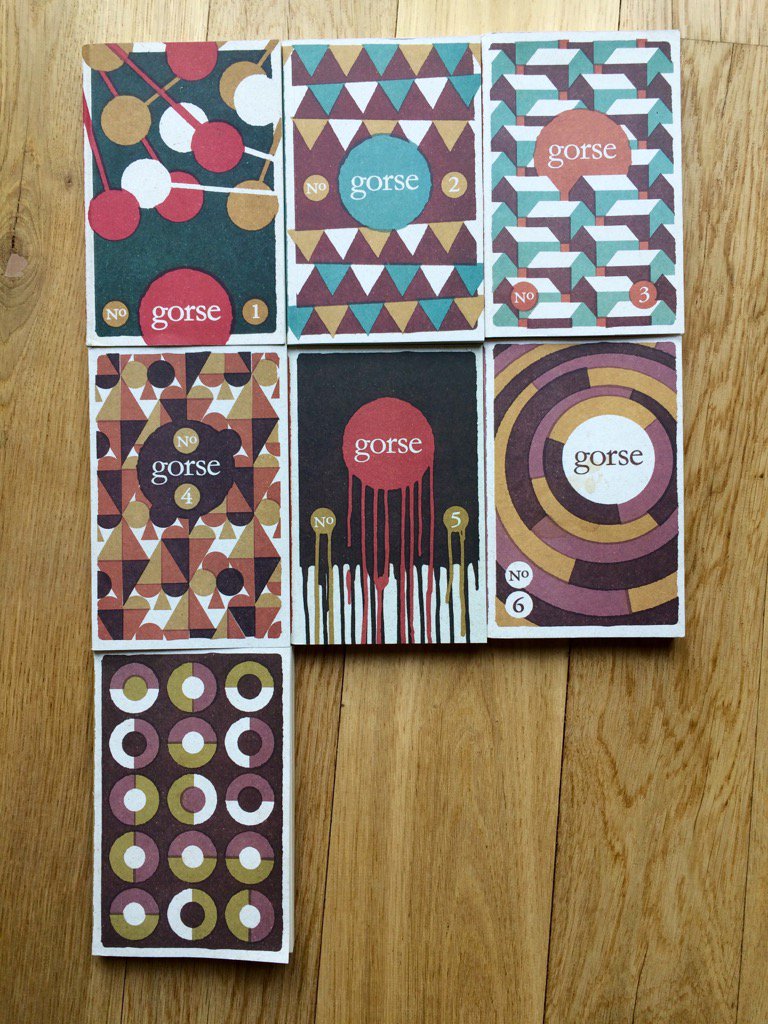

Haunting the margins: an essay in Gorse

I’m very pleased to see a new essay of mine in the latest edition of Gorse journal. For those who don’t know it, this is a new Irish literary journal edited by Susan Tomaselli that comes out three times a year and is now up to issue 7. I had a story in Issue 2 (Festschrift, later anthologised in Salt’s Best British Short Stories 2015) and and am made up to be back between their covers – quite exquisitely designed, as ever, by Niall McCormack.

Other writers featured in #7 include Scott Esposito, CD Rose and the White Review Short Story prize-winning Owen Booth. Other writers you might have heard of in previous issues include Darren Anderson, Louise Bennett, Kevin Breathnach, Claire-Brian Dillon, Rob Doyle, Lauren Elkin, Andrew Gallix, Niven Govinden, David Hayden, David Rose, Joanna Walsh and David Winters, and there are interviews with Geoff Dyer, Deborah Levy, Alan Moore, Lee Rourke.

My essay, ‘Marginalia’ grew out of a response to Ben Lerner’s essay ‘The Hatred of Poetry’ and explores traditional and contemporary uses of book margins and footers by writers such as Lerner, Maggie Nelson, Alasdair Gray, David Foster Wallace, Rebecca Solnit and Douglas Coupland.

A song lyric: End the Beguine

It’s been a long, hard Winter

And a short, sharp Spring

And you stand at the window (winder)

Like a character out of Pinter

And you don’t say a thing.

Oh, darling…

What’s the point in trying?

And where’s the use in sin?

The way that things are tending

Are we here to begin the ending

Or are we only ending the Beguine?

End the Beguine, end the Beguine

We go out where we came in

We’ve been through thick

And now by god you’re looking thin

You’re looking at the wrong end of the Beguine

Well I’m sick and tired of fighting

And frightened that I always win

The positions you’re defending

And the messages you’ve been sending

Are telling me we’re ending the Beguine

End the Beguine, end the Beguine

We go out where we came in

It’s just a trip upon

A ship that is sinking

And the band plays on till the end of the Beguine…

****

This lyric has been hanging around in my head for years. I could sing it to you, but try as I might, when I sit at the piano, I can’t find notes that fit it. Suffice it to say, it’s in a Noël Coward kind of vein.